A Great Anomic Era: IAN CHENG

Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works.

Anything that’s invented between when you’re fifteen and thirty-five is new and exciting and revolutionary and you can probably get a career in it.

Anything invented after you’re thirty-five is against the natural order of things.

-Douglas Adams, The Salmon of Doubt

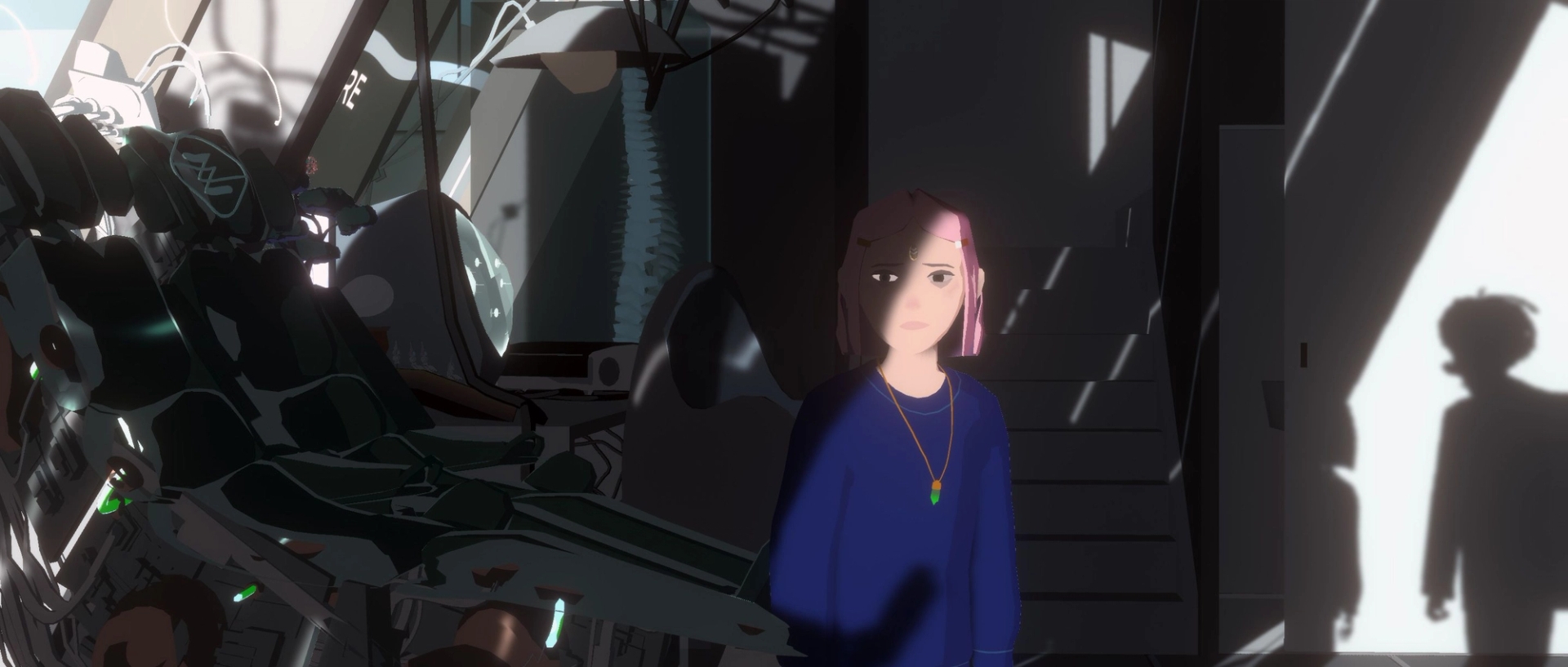

IAN CHENG has built a brave new world deep in the belly of Halle am Berghain. Presented by LAS (Light Art Space), the exhibition is a hypnotic, techno-psychedelic future in the grips of a “Great Anomic Era.” AI technology promises to relieve existential stress, by co-piloting human consciousness. “The Chalice Study” is the first of the eight-episode animated miniseries, “Life After BOB.”

Henry Levinson: Much of your work focuses on the idea of change. What is it about change that grabs your attention as an artist and how have you explored the idea of change throughout your practice?

Ian Cheng: In animation you can perfect every single millisecond forever, until someone forces your hand away. When I first started making art, I found myself so prone to want to perfect things.

I felt like if I started to make art that was more alive and could surprise me, I couldn't be so perfectionistic with it. It would activate something else in me, maybe something more necessary to navigate the world.

You know, the world is changing faster than ever. I think we all have whiplash about what to believe. What’s credible, what’s not credible, COVID etc. There's this texture to the world that somehow our nervous systems are improperly calibrated to deal with. Yet this is our reality, so we have to rise to the occasion.

I started making simulations around 2012 with this idea of creating something that had aliveness to it. I'm not an artist who uses human performers or live animals to achieve aliveness.

My corgi dog Mars always sleeps in the same way. He's really boring and middle-aged now, but he might roll over in a different way, or someone might come visit the apartment and he reacts a little bit differently than he has for the 99 other people who came to our apartment before, and it's a revelation.

I wanted to activate this, that aliveness that you get from expecting that a being’s behavior is predictable. Then you suddenly discover the latent space — of a person, of an animal, of a digital creature — that you didn't know it could ever express. The new behavior is coherent with its personality, but now it has the environmental opportunity to express that aspect of itself.

There's this notion of “Are you, you?” Is the portrait of you simply the facts of your life? That seems so limited.

Maybe you're the latent space of your potential. You can't be anything and everything. But there is some world of postures, roles, destinies, that you could be that hasn't been activated yet, or maybe never will be activated. But if it were to activate, I would say, “Oh, that's definitely still you.” Your essential character is still there. For me that’s a more accurate portrait of a person.

So, I'm obsessed with this idea of making artwork that has a sense of aliveness, because I think that's the art that excites me. Of course, when you make something alive, it's alive because it's changing. It's been my niche, but it's also under explored in art. Art that is itself alive.

HL: “Life After BOB” was built with a videogame engine called Unity. What is Unity? Why did you choose to build this piece using Unity, and what makes it uniquely special for telling a story like the one you wrote?

IC: You can think of Unity is for virtual worldmaking as what Photoshop is for image manipulation. Unity is designed for building interactive experiences, the main one being video games. When I first started making simulations, I thought of them as video games that play themselves. I didn't want to make a video game, which is its own crazy difficult challenge where you’re designing an experience for a player to interact with. I wanted to make a video game that could play itself so that it would achieve this aliveness. Unity was and still is a very popular video game engine at the time. It had the biggest ecosystem of developers, tools, youtube tutorials, people who knew how to use it. So, it became a very inviting ecosystem to make this new thing in.

In terms of making a film that way, it's quite unconventional. When we first started production on “Life After BOB” in 2020, I think the longest film made in Unity was just 10 minutes long. The exciting thing about Unity is it introduces all these new production processes. It makes animation cheaper, faster, and the ability to edit as a director very fluid. And the ability to make derivative experiences becomes easier and faster too: a VR version of the film would only take a few days to prototype. I could transform this virtual dollhouse I've constructed, this virtual film set with all the characters living all these other kinds of interactive experiences very fluidly.

This fluidity as an artist is a dream. To be able to imagine a project and all its octopus legs and then just be able to produce themquickly, try crazy ideas, see what’s promising.

HL: What are some other short films that have been made with Unity?

IC: There's one called Sonder by Neill Blomkamp, who made District 9. He also made a series of short films for Unity, using Unity, trying to make it at the level of production quality that his live action films have.

HL: Artificial Intelligence is a central part to “Life After BOB.” For a lot of people, myself included, AI represents something very scary. The current moment is very much so defined by an unfound amount of pressure. Rents are insane, energy prices are insane, and AI is something that a lot of governments and businesses are using to shore up efficiency or accuracy at the expense of people’s comfort or ability to relax.

What are your thoughts on people’s anxieties around AI, and when you're working on pieces which use AI as a central component to the storytelling, are you thinking about those anxieties as well?

IC: Absolutely. When I started writing this story, I was forced to make a dramatic argument, otherwise it would've been boring to write, and no one would want to watch it. So, how do you create drama? To create drama, you need conflicting perspectives. So while LAB contains a more familiar father-daughter story, it’s also an AI story that begged to be argued.

I had to generate different perspectives about AI. The character of Doctor Wong is very pro-AI, but in a very instrumental way. He wants AI to be useful as a tool, an inner life coach, to guide his daughter towards her destiny. To grow up and self-actualize.

The character of Z, on the other hand, is pro-AI too, but in a non-instrumental, and more appreciative way. Z wonders what are all the weird things AI could be used for that we can't even predict yet? Let's explore that.

There's also a whole class of characters called Humanistas, who are ideological luddites about AI. They’re critical of Dr Wong and Z, and scared that AI that can be beamed into your head and control your nervous system perverts the boundaries of what it means to be human. They're quite protective of that boundary.

So, in order just to write drama, I had to generate these perspectives out of myself, otherwise it wouldn't be an interesting story to tell.

The converse is, if I started this work and I presumed I knew exactly what AI will mean to us in the future, it would come off as propaganda, and cartoony in an ideological way — a two-dimensional picture of what we already think, know or fear.

I think so much of art and storytelling is trying to unpack and unfold something that you're scared of and don’t truly understand yet. I love this thing Michaela Cole, who wrote I May Destroy You, said in her Emmy speech — “Write the tale that scares you.”

That’s so resonant to me, because the thing that scares you is the thing that likely scares other people too, and it's the thing that may be too complex to approach with the rational mind. If you really write what scares you, you have the opportunity to go on a journey of unpacking what that is. And you can discover truths within the complexity of that question in a way that's non-academic, non-rational, and immersive.

HL: For a lot of creatives, especially graphic designers or animators, there are big debates as to what extent AI is going to be replacing image making. Have you had your own thoughts on this idea of what AI means for creative production?

IC: It's funny you ask if AI will do the job of an artist or an image maker. The questions behind “Life After BOB” was a more extreme version of your question “can an AI do the job of living your life better than you?”

I've used DALL·E, it’s super fun to use.

HL: It’s so addicting.

IC: It’s so addicting, that's the thing, it’s so addicting! It's a different quality, no one’s addicted to using Photoshop. But you're addicted to using this kind of oracle that's going to produce an image of the thing that you want. And you can correct it and get closer to the thing that you want. It can kind of dream for you. I think image makers will just level up. AI is not going to replace image making, or people who do that as their job or their passion, it's just another tool that everyone will just level up with.

If I project forward with my own kids, they're one and three years old, to when they're 15 and 17, if I ask myself honestly, are they going to have AI based tools to, I don't know, make a whole story book or even a movie in one afternoon? The answer is probably yes, and that's a good thing.

I think it's a cool thing for them that they can print their imagination much more fluidly than you or I can today. We can to draw or write to “print” our imagination immediately, but to make a fully realized film — it takes a lot of people to produce such a detailed vision. With AI-powered tools, it's going to be much faster. Then it will be about the quality of those visions that will be at stake. Look at everything DALL·E makes, some are better than others. Some people produce more imaginative prompts that activate a betterpart of the latent space of the DALL·E model.

It's a tool like anything else. You can imagine when the first camera, the first film cameras to come out. You can imagine painters at the time saying, “They're stealing our job.” But then, photography becomes his own thing. Motion pictures are born. Then we get movies, and we still have painters.

I have to remind myself that we have to look at the new on its own terms. If we look at it from a point of view of hysteria or scarcity or your vocation is being taken away, that's not actually the mindset that our kids will live. They won't have those same fears, and therefore reality won't be constructed in the same way because it's going to be populated by people who don't share those fears.

HL: I was thinking about my nieces and their prowess on the iPad. They sometimes understand how to fix the television better than I do. It's horrifying, it sends a chill down my spine. But I shouldn't be looking at it that way at all. It's just the way things go.

IC: Being connected is like air for them.

HL: We've talked about the future quite a bit now — I’d like to go into the past of storytelling. The Wiki for “Life After BOB” is populated with lots of classical Chinese books, poems, and stories. East Asian motifs are used heavily throughout the piece, and many of the characters themselves are of East Asian backgrounds. In regards to the background materials that inspired the development of the story, which ones were particularly important for this film and why?

IC: When I was writing LAB and starting to draw images of what this thing might look like, I kept thinking, the main audiences for my work are primarily people who go to Western institutions. That's where I've been shown the most. But I really want to make a work that could resonate in the East, in China, Korea and Japan, Thailand, the Philippines. That there would be something here for them that was resonant. This is a movie about parenting. It's about a father and daughter. Maybe I was kind of exorcising some aspect of my own ancestry as well as the lives of my half-Asian kids.

We have this 20th century notion that the world is statically defined: First World, Second World, Third world. High class versus low class. I think this is an outdated model of looking at how humanity behaves. It seems more relevant to think in terms of change. “Is a country an ascending country?” “Is a person’s class ascending or is it descending?” It's the delta, it’s the change that matters. You can have a very rich person who's lived a very static life and emotionally they feel very depressed. They're psychologically or existentially very poor in that sense, because they're in a descending trajectory. Their future isn't going up it’s going down, draining the bank account slowly across generations. There's no innovation in the family business. You could say they're part of the descending class even though they're materially high class.

I thought I want to make a film for people in ascending cultures, I want to make people in descending cultures feel that they could become ascending. And I think that's why there's all this dialogue and thematics in the film about renegotiating the script of your life. Maybe you’re a young person, and the script that your parents gave you leads to a descending life. A young person should feel optimism about the future, even though the world is really twisted, fucked up, and weird. There’s also a lot going on that is generative and fertile and a new frontier. To give younger audiences a sense that you could still see a world that’s twisted and complicated as a place with ascending possibilities available to anyone who learns to navigate it. I wanted to depict that in “Life After BOB.” I hope the audience feels a certain ascension in the film, and if it had one drift, it's more towards the ascending side rather than a dystopian side.

I wanted to address an Asian audience too who I have a lot of optimism for.

HL: I’ve read in a few places that one of the reasons why Western audiences found Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell particularly fascinating was because it was dealing with so many cultural motifs that they weren't familiar with. But for Japanese audiences, it was compelling because it was a new interpretation of a concept they were already familiar with, objects which can have a spirit.

Of course there are huge differences between storytelling from a Japanese background to a Chinese perspective. But, I still wondered if storytelling from a Chinese, or Chinese-American, perspective has a particular ability to breathe life into stories about AI?

IC: I'm more initially inspired by Korean cinema. I grew up in LA, and a lot of my friends were Korean or Korean American. We showed “Life After BOB” in March at the Leeum Museum of Art in Seoul, and we found that it was really resonant with young people in Korea. This is a dream of mine, that we would show it in Korea and that it would actually hit in some way. There's something about Korea that is of course ascending. But there's also this confluence of Korea being a very media literate society, it's very technologically foward. But it's also so traditional in terms of family and the respect for an overly attached and in debted structure between parent and child.

The basic parent child drama between Dr Wong and Chalice seemed to be very resonant, this idea that you're under the thumb of your parents’ expectations and owe your parents a debt. In a way, I was more inspired by trying to play with those elements I see so often in Korean cinema. I love Korean cinema because they do such radical formal things with cinematography and pacing and tone. And with weird storytelling like Park Chan-wook’s films. Have you seen Thirst, the vampire movie he made? It shifts between horror and comedy in a beat. Or The Handmaiden where the genre seems to shift based on which character perspective you’re in? But then these same films are also about classical, well-trodden Korean family drama. You can't escape it. I love this confluence of very radical and very traditional topics smashing against each other and having to become a monster together.