ADRIAN VAN HOOYDONK: It Was My Dream Job

Speaking to ADRIAN VAN HOOYDONK on a warm summer evening outside a Munich restaurant, I realized just how differently our respective careers have taken shape. In the early 1990s, a common friend introduced us while we were both new to Munich – he had just graduated from the Art Center Europe in Vevey, Switzerland, and I from the Royal College of Art in London. Adrian was just starting to work for BMW, and I was setting up my own studio as an industrial designer. Employment versus independence. Corporate culture versus authorship. Two decades of working at opposite ends of the same profession. Adrian has come a long way, or rather, climbed high: starting as a hopeful young design graduate entering a large corporation, he has made it to the very top of the hierarchy.

Earlier this year, at just 45, Adrian van Hooydonk was appointed Director of Design for BMW Group, including BMW cars, BMW motorbikes, MINI, Rolls-Royce, and DesignworksUSA. Because of the fierce competition among top car companies, car designers are admonished to remain very secretive about what they do until the work is officially launched. By now, however, Adrian von Hooydonk has plenty of significant projects to his credit at BMW to talk about – and he does so with a certain boyish wit, which by no means deflects his professional sovereignty that stands synonymous with BMW Group’s dynamic design culture.

KONSTANTIN GRCIC: We take cars for granted, even though they’re hugely complex products! It’s beyond most people’s imagination what designing them entails. Was becoming a car designer a naïve childhood dream for you, or rather a slow-built career?

ADRIAN VAN HOOYDONK: It was my dream job. Many kids dream of cars, but coming from Holland, a very small country with no car industry to speak of –

– Apart from DAF.

Yes, apart from DAF, which was on its way down while I was growing up. So it didn’t look like a huge possibility as a Dutch kid. To me, the whole idea of designing cars was unattainable– I didn’t know how it was done or where you could do it. Then I learned about industrial design, which is a tradition in Holland, especially in the 1980s. Our money was well designed. Our stamps were well designed. Our architecture, our furniture, our public spaces. So the concept of design was something you could grasp in Holland. But I still thought car design was impossible. After my studies at Delft Polytechnic University, I went to Italy where I started working in product design in the early 1990s.

“We want to express luxury in a modern way, which seems like a contradiction at first, but it’s possible.”

That was after the Memphis group, which has irreversibly liberated design from many constraints. I think, as designers of our generation, we profit immensely from that. Design was becoming more and more popular, and it seemed that everything was possible.

I did an internship in Milan at the studio of Rodolfo Bonetto when the industry was still dominated by old men. But at least I got a glimpse of design done the Italian way. At that time, Bonetto was also in charge of interior design for Fiat, so the possibility of making cars returned. It was so attractive to me because a car is a moving object, or an object that moves under its own power. And of course, it has a lot of surface to discover.

Do you remember any particular car that inspired you at that time?

There were some very futuristic-looking Lancias with bizarre interiors – the one with the holes, for instance.

I think that was Mario Bellini’s design – beautiful! It was never a popular car, but it was significant for design.

For me, Bellini was one of the most influential designers. Another one of his designs that I love – and I own one – is the Divisumma calculator from the 1970s.

[laughs] Do you have one that actually works?

I haven’t plugged it in a while, but you can push the buttons all day long.

They become rather morbid objects because the rubber disintegrates with the UV light.

The color is sort of fading on the membrane, but it still looks good. Anyway, working in Italy’s international environment gave me the idea that maybe this car thing was possible after all.

“A BMW is meant to move, so it should look like it’s moving even while standing still. And it should actually look like a lot of fun.”

At that time there were really only two schools for automobile design – the Art Center in Vevey and the RCA in London– which is incredible considering the power of the industry. I find it quite beautiful. It makes it more human, more personal.

It’s changed, which is a good thing; you need more diversity. I can tell from a set of sketches which school a person comes from, which may not be what you want. A useful set of skills certainly comes out of that training, but the goal is to assemble a team of designers in which each person has his or her own style. Of course once they start working they will need to speculate on what the company is as a whole, but fundamentally the vision comes from individuals.

What do you mean by “skill set”? In my field of design, schools today don’t teach any skills. I think it’s desperate –almost fatal.

Designing a car is a craft. A lot of people can draw, but drawing a car is difficult. The key is how to translate a fancy sketch into three dimensions – it has to be exaggerated. When you start with 3D, you deal with the surface, which you initially depict with clay modeling. You can do anything with clay. You can add. You can subtract. Everything is possible. So in school, you learn that your own sketch, which you thought you understood and could only interpret in one way, actually has many interpretations. Then imagine somebody else interpreting your sketches. You can’t just put up a sketch and say, “That’s it. Build it.” That wouldn’t work very well in the car industry.

You said you have an engineering background. Do automobile designers need to know how a car works?

They know a lot about, for instance, how sheet metal or aluminum can be formed. They know a lot about aerodynamics. They know the basics of how a drive chain works, and how a car operates. But they don’t know much about what goes on under the hood. That’s why you need to be able to read a section, and communicate with an engineer. If an engineer is telling you why something can’t work in a certain way, you better understand enough to come up with a different solution.

Within this very powerful, but small and competitive industry, you’ve managed to climb quite high. It probably has to do with all the things previously mentioned: skills, structural understanding, communication, etc. But what makes you better than the others? Why are you so good?

There’s how I feel it happened, and how I think that it happened, which is more political. I feel like I was sort of taken down this turbulent stream with a lot of other people. At some point I was washed ashore, and I was the only one left. To be more analytical, you need to have the two kinds of confidence for a job like mine. One is the design side. My design team needs to trust me, almost blindly, that when I go and talk to the top management, I’ll speak in the interest of the best possible design. Then the management has to trust me blindly as well, because they don’t know what I really do all day long – we only meet every two weeks. I guess that, somehow, both sides do trust me. If only one side trusts you, you won’t make it to this position. That’s the most analytical I can be about myself.

So, you are a BMW man.

I’ve grown into it. It was one of the companies I was interested in as a student, because not only are they fun cars to drive, but the company’s design culture is very unique. I would imagine people looking at BMW from the outside see a strict German company that has a plan and just executes it. But every year I’m amazed by the variety of projects and the openness with which the company operates. An idea can come from anywhere, and this highly specialized design process has been protected. After all, people initially buy a product because of its visual impact. When people buy the same brand a second time, it’s because they really enjoy using it as well. I think that’s corporate culture, and I’ve grown to respect it.

In the end, the work you do is seen as a BMW and not an Adrian van Hooydonk. Are you comfortable working behind a brand?

The brand will always be better known than I will be as a designer – it also helps that the brand name is a lot shorter than my last name! But I think that the age of brand as an anonymous entity is over – it doesn’t work. Today customers want to know where something comes from, whether it has a history and what that history means, and ultimately who’s behind it. That’s why I – and other members of my team – do get a lot of visibility.

BMW produces premium vehicles, so whatever we do must have strong character – we don’t aim for the mass market. Another important aspect is BMW’s corporate culture– and Chris Bangle didn’t start this, he benefitted from it. BMW has a strong belief that you should never rest on your achievements. Just because you were at the forefront last year doesn’t mean that you’ll be there next year. And if you want to have the most advanced technology, then you have to have the most advanced-looking design. How else can you explain to your customers how clever you really are? You can transmit all of this much easier through design than by explaining what the car can do.

Despite being a global brand, would it be true to say that BMW’s DNA lies in its Bavarian roots?

I do see something in Bavarian culture that invites all of this. In Bavaria they sometimes say that if you’re not being scolded, then you’re being complimented. It sounds better in Bavarian, but it basically means that, in this culture, people tend to focus on what they can do better instead of dwelling on what they did well.

What makes a BMW car?

A BMW is meant to move, so it should look like it’s moving even while standing still. And it should actually look like a lot of fun.

Is Germany still a place where cars come from?

It’s not the only country where quality comes from. But quality combined with a certain type of solidity is maybe German. Precision seems to be another thing that people associate with products engineered in Germany — they no longer have to be built in Germany. In terms of design, I wouldn’t say BMW is German. I would say it’s European. I don’t think you can pinpoint it to Germany. Design isn’t like that anymore.

Are most of your designers European?

No, they’re very international. We have almost 50 nationalities coming from design schools all over the world. But I think good designers understand what a particular brand needs or might want to express.

How do you actually design a BMW – I mean, what is the process from start to finish?

The design phase takes about a year. I sit down with marketing colleagues and engineers, and we talk about what we think it should be. It has a workshop format, and only takes a day to get going. Then the marketing people present detailed customer research to show what the design needs to fulfill. The engineers talk about what they want to incorporate, and then we, as a design team, discuss how we see the future and how we think the world will evolve. Between all of these groups there is, of course, always a mismatch in the beginning. But still, in just one day we determine what we think the character traits of this new, yet-to-be-designed car should be. Then we start the design competition, both for the interior and the exterior. In the beginning we have about 40-50 designers sketching, which takes about six weeks. Then we do scale models or computer models of about eight sketches that I select, and later we design about four full-size exteriors and four full-size interiors, which are presented to the board of management, including the CEO. At that point we’re about half a year into the program.

So, at that point, you still haven’t put a single line on a piece of paper?

I design with my mouth. Sometimes it’s more effective to just sketch what I think, but we work with other designers’ sketches. It would be dangerous for a big company to depend solely on one person.

But you developed the voice you have today in the company by actually designing cars. For example, the strange-looking 6 and 7 Series bear your signature.

I did design both those cars, but they’re attributed to Chris Bangle. The chief designer is responsible for everything. Even if people internally know who designed what, for the outside world, there’s only one name that’s responsible for everything.

What was the first Adrian van Hooydonk car?

The new 7 Series was the first car that I was responsible for from its conception to how it looks on the road now. After that it was the Z4. Also some show cars like the BMW Concept CS or the BMW M1 Hommage. There are also a lot of BMWs yet to come.

The 7 Series got a lot of slack, which must have been quite character-building. Initially, you brought something to the luxury market – which at that time was dominated by the sophisticated Mercedes S-Class – that was still very raw. The media railed the design, whereas the market bought it and approved, which eventually allowed the car to evolve towards the refinement it has today.

We’re not the oldest car company in the world, so we don’t feel like we should go for traditional luxury. We want to express luxury in a modern way, which seems like a contradiction at first, but it’s possible. With the 7 Series, we changed the proportions, the design, and the user interfaces, which are brave moves. But now it has elegance, with a more complex surface treatment. At first glance it’s easy to digest, but once you get closer you realize that it’s quite complicated and has a great depth in terms of design. For me, the 7 Series that’s out now feels complete. But then again, maybe what we set out to do wasn’t achievable in one generation.

Design is all about evolution – it’s impossible to get things right the first time. But there are always breaking points in these evolutions, where the project takes significant turns.

The 7 Series was always number two in its market, and BMW was clever enough to realize that in order to overtake the competition, it needed to take bigger steps, and risks. Of course every CEO’s dream is to have minimal risk and maximum success, but that’s not how it works. But at the moment, the 7 Series is leading its market segment worldwide.

I think that cars, more than most other products, reflect today’s society. They mirror how we live, and more specifically, our economic status. The past few years have been extremely prosperous. They were very good years for the industry, and for us working in the creative field. Cars had been getting bigger, faster, and more luxurious. Then, all of a sudden, there was a rude awakening with the economic downturn, and of course there are also ecological problems. As a company that looks very much towards the future, how was BMW prepared for this?

We went to school when design was still relatively unknown– we always had to explain our profession. For the past ten years, however, it became almost over-hyped – design was everywhere as a kind of sensation. But we all knew it couldn’t last, and we anticipated this collapse for years, especially the CO2 issues. The new 7 Series has a bigger engine, but it weighs 50 kilos less than the previous model, which is very hard to do. It uses a lot less fuel as well. We’ve also been working with new technologies that are labeled “Efficient Dynamics”: there are things like “engine start/stop,” where the engine switches off when you stop at a traffic light. We’re not really interested in engine power or making a car faster any more. What’s interesting now is what we call “power to weight ratio.” If you make a lighter car, you don’t need as much power. This ratio is also what makes a car go fast around a corner, whereas pure power just makes it go fast along a straight line.

But going fast is still fun. So ideally, ecologically advanced cars shouldn’t mean slower cars. There’s a big boom right now with electric cars, but surely that’s not the only solution. Perhaps they’re useful for city driving, but not for long-distance travel.

Everyone is struggling with these questions. Every time there is an oil crisis, companies try to convince people to drastically change their habits, which of course no one wants to do. We’re working on a concept car for the Frankfurt Motor Show that is the vision of how we think people can still have fun without feeling guilty. Future technologies will certainly combine petrol engines with electric drive, but the energy has to come from somewhere else. Where exactly is not clear yet.

There’s solar energy and Desertec.

But this combination of fuel and electric drive we’re moving towards needs a lot of infrastructure – batteries take up half the interior of a car and need to be recharged every 100 kilometers. We’re also developing hydrogen-based cars, which brings us closer to solving the limited-resource issue, because hydrogen can store large amounts of energy and is made up simply of water and sunlight.

What about a more economical car? BMW finally introduced its concept car, the GINA, last year, which explores the idea that a car can be built without tools, eliminating most investment costs. Is this something of the future?

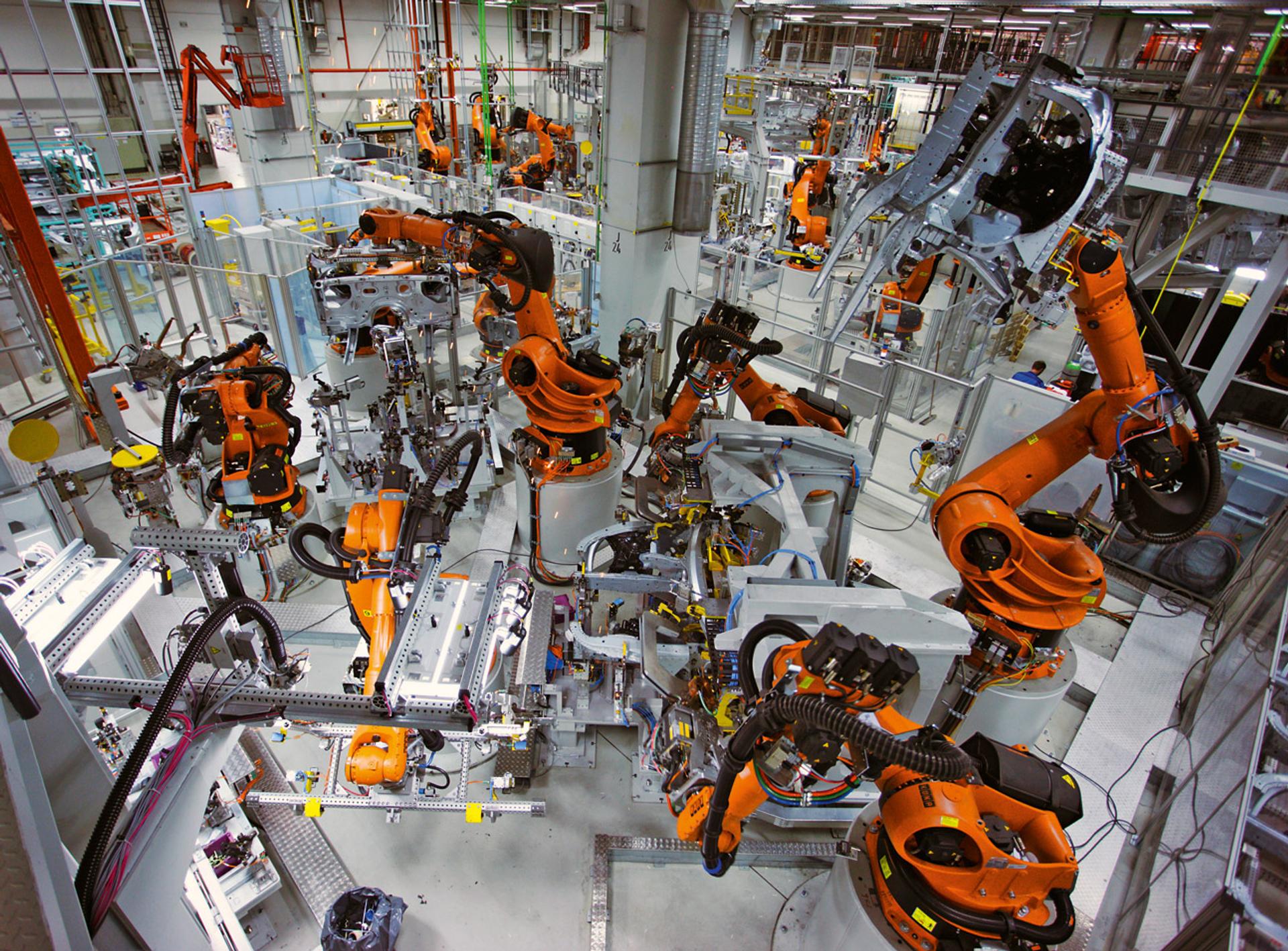

I think so. The GINA concept car was designed and built to challenge the basic conceptions of how the industry works. When you invest in huge tools, you’re locked into a cycle in which you have to produce a certain number of vehicles in order to recuperate that investment. So if sales drop, a company literally chokes. Right now the financial crisis is revealing just how volatile this industry is. Considering this, I see the GINA as something more important than ever before. If we could, as an industry, liberate ourselves from big investment, we would be more flexible. At the moment it’s only a vision because it’s not easy to achieve. If you’ve ever seen one of our factories you realize how crucial tooling is – it’s almost prehistoric how the whole ground shakes from our injection-molded presses. But it’s how we do things, and it’s also a huge engineering feat to instantaneously make a huge piece of metal with two big bangs.

But there are intermediaries between the GINA and how cars are made today. People would be surprised by the amount of plastic parts a car has. How are materials changing the way cars are designed today?

I’ve seen lamps done with rapid prototyping, which used to be the way designers produced a quick mock-up. But people are now putting that stuff on the market. Whether it looks good or not is another story; but there are no tools involved. Who says we can’t make certain parts of a car by rapid prototyping? Traditionally, people used to think of materials just as plastic, metal, steel, or aluminum. We are now moving into a territory that goes beyond that: more than ever the material is inspiring the designer, whereas before he was just dictating the shape and someone else was figuring out how to make it.

But beyond material, what’s important today is total energy calculation, or how much energy it takes to make something. A lot of people talk about recycling, but what they really mean is down-cycling, because re-used materials have a lower quality than before. True recycling, however, is something that we’re looking into right now.

At this year’s International Motor Show in Frankfurt, BMW introduced several futuristic concepts. Foreseeing the future is such a cliché people have about designers, but in your case it seems to be almost true. The incredible lead time of developing cars makes it necessary for an automotive designer to anticipate what will be in five years, even ten years. Can you give us just a key word, a brief hint – what is on your mind today that we can’t even imagine for 2020?

At this moment in time it is probably hard to imagine a positive future for individual mobility, let alone a sporty kind of mobility. For the Frankfurt Motor Show we designed a sports car of the future. A car that combines driving fun and emotion with efficiency, or in other words a very low fuel consumption and emission. For now this is just a vision, but in ten years it will have become a reality.