ANDRO WEKUA

Other Skies Tell Other Stories: ANDRO WEKUA

In the West, we are taught from a young age not to stare. Not at the woman in the metro, not at the man in the store, not even at our friends in school. It is considered rude, uncouth, and unwelcome. To stare is thought to be confrontational. The eyes are, after all, a violent medium. Which follows that, perhaps because violence in the West has become remote, we find the stare all the more disturbing. As if it were one of the only remaining vestiges from a time when we understood the primacy of meaning instinctively, when a comment sparked a duel, or a stare could be epic … The further one goes East, the more the eyes have managed to retain both their potential for violence and a certain decorum disarming it.

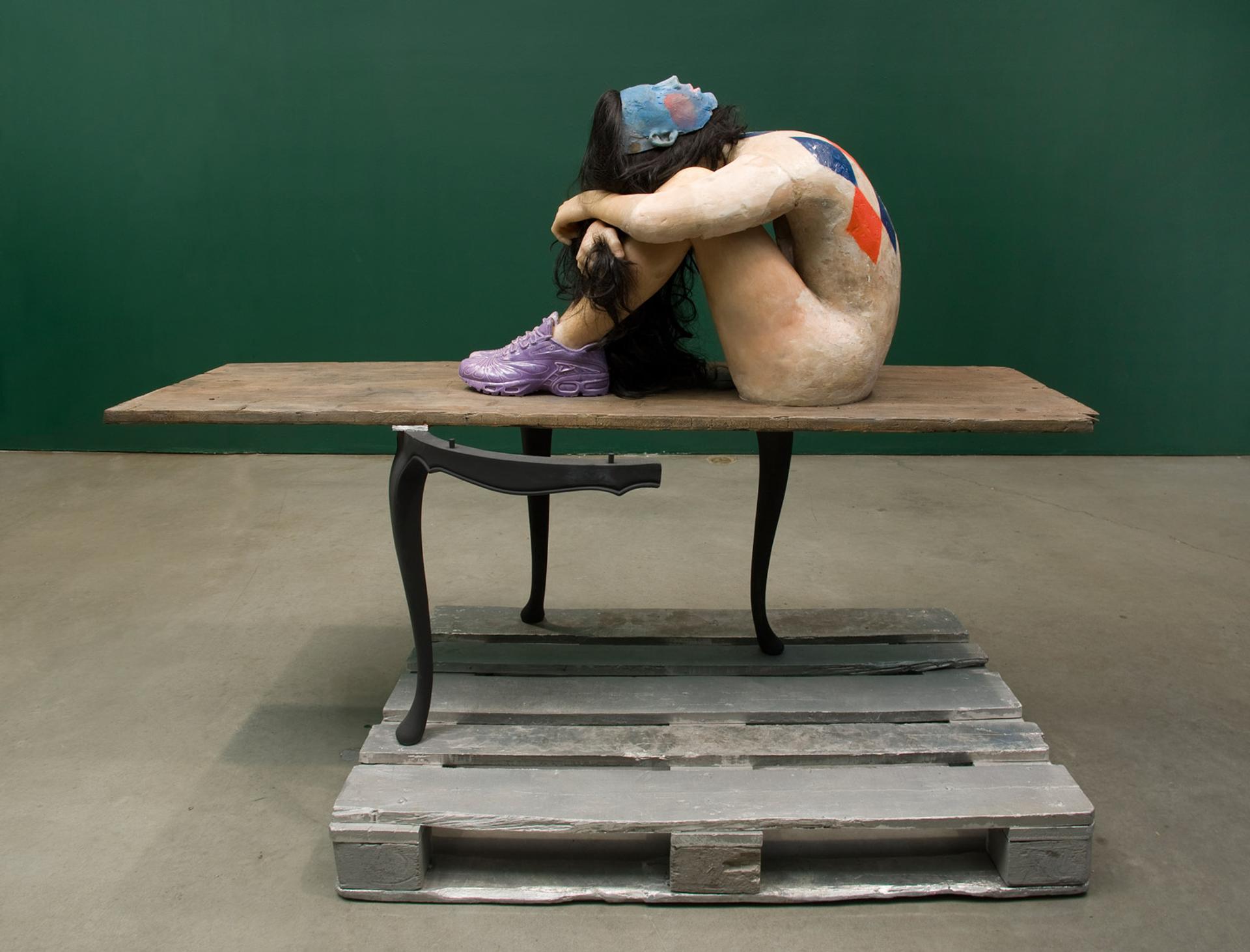

One does not look at Andro Wekua’s work. One stares – at the Technicolor seeping through a pierced old-world modernism; at the muzzled gazes of mannequins, disarmingly half-dressed. We stare at that which we do not understand, and Wekua’s figures, landscapes, and palette come from a parallel universe, brushing up against ours, overlapping in incidental imagery, but distinctly foreign. It is a world inhabited by peoples who are neither the hopeful Homo sapiens nor the melancholic Homo Sovieticus – or is it the other way around? – to which the rest of us belong and have grown accustomed.

Wekua’s exhibition titles – “My Bike and Your Swamp,” “Wait to Wait” – provide a refreshing twostep to an impressive succession of blockbuster shows in Brussels (Wiels), New York (Barbara Gladstone), and London (Camden Arts Centre), all within the span of little more than a year. The twilight sway of identification in Wekua’s work stems in part from his origins. He was born in Sukhumi, Georgia in 1977, the capital of Abkhazia and a town on the Black Sea, inaccessible to Georgians since the early 1990s. The region is one of many frozen conflicts within the post-Soviet sphere: history has moved on, even if the people have not, cannot. The region’s independence is recognized only by the retro troika of Russia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela. The artist does not, however, deal discursively with the theme of exile. His Get out of my room (2006) presents an inner psychology equally at ease within the cosmology of teenage angst as within early 20th-century scenography. In 2010, in a supposedly post-historical, post-racial world, surely we can move beyond identity politics: his and our selves, as it were, are saddled with a simultaneous collapse and proliferation of geography. We belong to many places, remember few, and pledge allegiance to none. A certain indistinguishability – if resistance was the rage of modernity then escape has become our arsenal of necessity – allows us to breathe in without the surgical mask to filter out meaning, but we remain apprehensive of where to go for our next gasp. This indistinguishability becomes both our handicap and the card up our sleeve.

Wekua is based between Zurich and Berlin, where I visited him in his studio. The softness of his phrases and features belie a fierce intelligence, one shaped by a healthy distance from his surroundings, be they the Caucasus or Kreuzberg. I am reminded of Czeslaw Milosz, the Polish Nobel laureate whose passionate words about the second half of the 20th century have survived well into the first half of the 21st. Both navigate the landmines of identity and exile with effortless immediacy – Milosz in poetry, novels, and essays; Wekua in painting, collage, installation, and sculpture. So it is that we may read Wekua through Milosz, and try to better understand that rare artistic feat: the hat trick of attraction, repulsion, and confusion made necessary by today’s tyranny of transparency.

–Payam Sharif

MY INTENTION

I AM HERE. Those three words contain all that can be said – you begin with those words and you return to them. Here means on this earth, on this continent, and no other, in this city and no other, in this epoch I call mine, this century, this year. I was given no other place, no other time, and I touch my desk to defend myself against the feeling that my own body is transient. This is all very fundamental, but, after all, the science of life depends on the gradual discovery of fundamental truths.

I have written on various subjects, and not, for the most part, as I would have wished. Nor will I realize my long-standing intention this time. But I am always aware that what I want is impossible to achieve. I would need the ability to communicate my full amazement at “being here” in one unattainable sentence which would simultaneously transmit the smell and texture of my skin, everything stored in my memory, and all I now assent to, dissent from. However, in pursuing the impossible, I did learn something. Each of us is so ashamed of his own helplessness and ignorance that he considers it appropriate to communicate only what he thinks others will understand. There are, however, times when somehow we slowly divest ourselves of that shame and begin to speak openly about all the things we do not understand. If I am not wise, then why must I pretend to be? If I am lost, why must I pretend to have ready counsel for my contemporaries? But perhaps the value of communication depends on the acknowledgment of one’s limits, which, mysteriously, are also limits common to many others; and aren’t these the same limits of a hundred or a thousand years ago? And when the air is filled with the clamor of analysis and conclusion, would it be entirely useless to admit you do not understand?

I have read many books, but to place all those volumes on top of one another and stand on them would not add a cubit to my stature. Their learned terms are of little use when I attempt to seize naked experience, which eludes all accepted ideas. To borrow their language can be helpful in many ways, but it also leads imperceptibly into a self-contained labyrinth, leaving us in alien corridors which allow no exit. And so I must offer resistance, check every moment to be sure I am not departing from what I have actually experienced on my own, what I myself have touched. I cannot invent a new language and I use the one I was first taught, but I can distinguish, I hope, between what is mine and what is merely fashionable. I cannot expel from memory the books I have read, their contending theories and philosophies, but I am free to be suspicious and to ask naïve questions instead of joining the chorus which affirms and denies.

[…]The words of a prayer two millennia old, the celestial music created by a composter in a wig and jabot make me ask why I, too, am here, why me? Shouldn’t one evaluate his chances beforehand – either equal the best or say nothing? Right at this moment, as I put these marks to paper, countless others are doing the same, and our books in their brightly colored jackets will be added to that mass of things in which names and titles sink and vanish. No doubt, also at this very moment, someone is standing in a book store and, faced with the sight of those splendid and vain ambitions, is making his decision – silence is better. That single phrase which, were it truly weighted, would suffice as a life’s work. However, here, now, I have the courage to speak, a sort of secondary courage, not blind. Perhaps it is my stubbornness in pursuit of that single sentence. Or perhaps it is my old fearlessness, temperament, fate, a search for a new dodge.

–From Czeslaw Milosz’s To Begin Where I Am: Selected Essays (New York, 2002)