All Art Has Been Contemporary: AXEL VERVOORDT

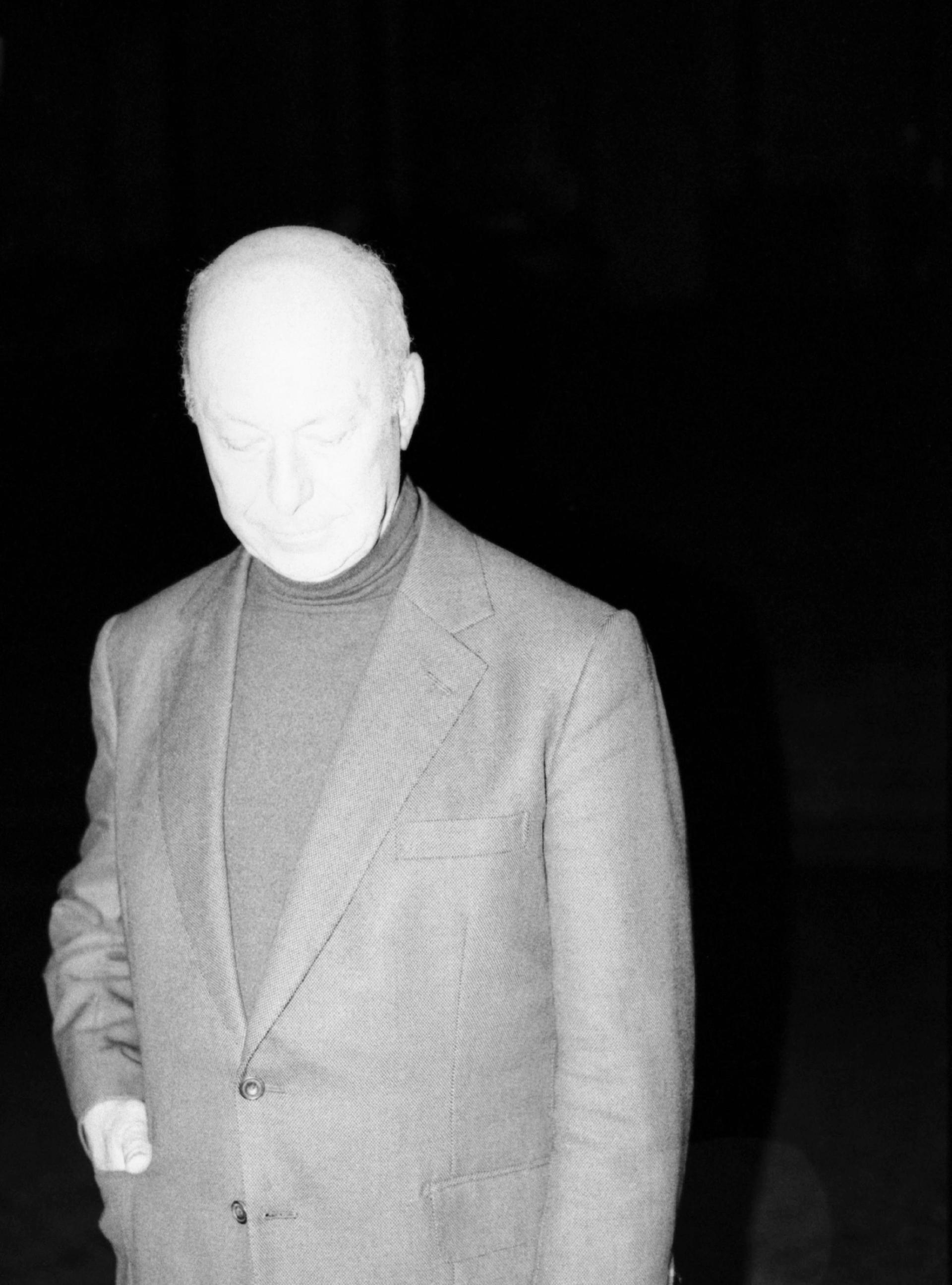

Belgian art collector and interior decorator Axel Vervoordt has been making waves since the 1970s with his penchant for pan-historical adventure and an unrivaled nose for quality. Interviewed at his castle outside of Antwerp, Vervoordt discusses his exhibition for the 2009 Venice Biennale, what Zen and Zurbarán have to do with one another, and why beauty still offers a safe haven from the dire world economy.

Around 400 years ago, a German nobleman took a piece of solid elephant ivory to a lathe, turning out a tall, spiraling cup after many days. The raw ivory itself probably travelled across the Alps from Venice, where it would have sailed in from Egypt, traded along the Cairo spice routes for thick Italian silks. Whether it came off an Indian or African animal is immaterial at this point (though probably it was African), nor do we know exactly who produced this sublime trophy (called a potak actually), only that he was a member of a royal family or the high nobility – those who exercised the sole privilege of creating such pièces de maîtrise. Honing his craft over years, the artist would fashion these pieces to show off his skill with the lathe, while also engaging in a kind of contemplative philosophy. The potak is both high and slender, gracefully swelling in the middle as a line works its way down from the finial at the crown to the spread of the foot. Carving this cochlear track was also a scientific enterprise, the delicate folds and subtle shifts of line demanding an eye towards the abstract math that was akin to contemporary philosophic inquiries into time and space: The potak revolves in search of the harmony of the cosmos, questioning the infinity of its own spiral, the resolution to an equation that has no fixed terms and – like the story of this piece itself – no truly knowable beginning and an unforeseen end.

This turned masterpiece made its way through the centuries and now sits on a crowded shelf in a drawing room of Axel Vervoordt’s castle in ’s-Gravenwezel. The piece was featured two years ago during the Venice Biennale at “Artempo,” a show at the Palazzo Fortuny inspired by Vervoordt’s lifetime of work. “Artempo: Where Time Becomes Art” was only the first of what Vervoordt calls the “Trilogy,” with “Academia: Qui es-tu?” following in 2008 at the Chapelle de L’École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The concluding exhibition takes place during the Venice Biennale this summer. Entitled “In-finitum,” the Palazzo Fortuny will again be filled with elite jetsam from across history, works whose combination without regard to vintage or style has become Vervoordt’s curatorial signature. Unlike his booths at more commercial art fairs, these are showcases for the broad philosophy behind his diverse collection, providing the visual inspiration for – and illustration of – his guiding principles: “harmony, contemplation, respect … but also the contemporary.” All achieved through a life that appears to be filled only with what is very, almost unbearably, beautiful: rooms with walls of gilded Cordoba leather, austere stone Bactrian devotional objects, shelves of precious rarities and animal oddities, Chinese gonshi “scholar’s stones,” and paintings from masters old and new, with a heavy emphasis on the purist art movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. It’s a latter day Wunderkammer, anchored by the Tang dynasty on one side and Lucio Fontana on the other.

Roberta Smith, longtime art critic at The New York Times, wrote about the opening of “Artempo” that the “fabulously eclectic exhibition … regularly blurs the line between art and nature … But it goes further, creating a site-specific, wildly stimulating environment of all kinds of artifacts, functional objects and natural specimens.” Not messy exactly, but more mimicking the meandering habit of time itself: a romp through the detritus of high and low culture is evidenced both in Vervoordt’s work and play. Art imitating life for once. His home itself is clean and light, though the castle was very much occupied even on the chilly Tuesday in early March when I visited, with a bustle of low-key staff who appeared and disappeared through the camouflaged service doors. But it also had a dusty character to it in the timeworn, careworn sense: slightly roughed-up and used underneath the polish and glamour. Which is exactly Vervoordt’s goal.

“I want to be connected to the Earth,” he tells me later that day – which sometimes means specially mixing his paints with costly pure mineral pigments or even ox blood. However, “something is not interesting just because it is expensive,” and Vervoordt’s style is not exactly that savvy combo of high- and low-end that has become so fashionable lately. While everything here definitely has a pedigree – assured of by the small army of art historians, researchers, restorers, and scouts on his team – he is uninterested in labels, usually forgoing them in his installations, preferring to let the inherent magnetism of the object or artwork itself work magic on the room.

Originally, Gravenwezel Castle's was constructed as a defensive hold for the lords of Bergen op Zoom in the 12th century and was rebuilt beginning in the 1740s as a country estate, with a French Régence façade and a large park. Everything has been carefully refurbished by Vervoordt and his wife May since they bought the property in the early ‘80s, making it their permanent home as well as the showroom for their art, antiques, and decorating business. The office and display spaces are now split with the Kanaal, a former 19th-century genever distillery run by their son Boris, nearby on the Albert canal leading to Antwerp’s busy port. The industrial space of the Kanaal building has enough room to house many of the 12,000-plus pieces of the newly established Vervoordt Foundation. The Foundation is an outgrowth from the cycle of exhibitions that began with “Artempo” and culminates in “In-finitum,” and it will encompass both curatorial and educational projects at the Kanaal as well as the ongoing collection process at the castle.

In fact, much of what a visitor sees even in the castle is for sale – a Willy Wonka chocolate factory for the grown up connoisseur, where you can touch all the art and the velvet ropes across the Louis XVI divans have been removed. Chris Dercon, the Belgian-born director of the contemporary Haus der Kunst in Munich, says that “Axel is a little like our Collette [the infamous Parisian concept store], or a Carla Sozzani [the mind behind Milan’s 10 Corso Como luxury souk]. He’s our Moss [the eclectic SoHo housewares shop in New York]. Maybe ‘moss,’ as in biology is a good description of Axel’s renderings.” This is in reference to Vervoordt’s organic collecting sensibility, leading first by instinct. “Of course Axel’s practice is a kind of Belgian thing, too. First of all, we are paranoiac collectors in Belgium, think of ‘collecting’ artists and their interiors – present in their art – like Henri de Braekeleer, Antoine Wiertz, James Ensor, René Magritte, Marcel Broodthaers … even Martin Margiela and Dries Van Noten!”

When asked whether there was any political motivation behind his democratic approach to visitors as well as styling, “No, no, no,” Vervoordt replies. “I’m very casual here. I want to find the commonality in all these pieces. What’s common between the old and the new. That’s what makes art relevant. The old and the new. That’s what is important. Some of these ancient pieces feel so contemporary.” He laughs, “I am Flemish, but I’m Belgian. I don’t want to see the country break up.”

Though Belgium managed to have a government the week we met, the impulse to work both with and against the centrifugal aspects of time – the scattering, shattering forces of deep history – are staged throughout Vervoordt’s home. Murals from the Fugger banking family mansion in Antwerp, painted by the school of Rubens, were rescued before the house was demolished and installed in a downstairs library. On a tour through the lower floors of the main house we passed by an ancient granite bust of the Egyptian warrior goddess Sekhmet loaded onto a dolly for transport to TEFAF (The European Fine Art Fair) in Maastricht later that month. The lioness face was obscured by a sideways breakage, though the reverential craftsmanship was plain to see, and the shiver of standing close to something so very old still caused a slight air of mysticism to waft about her, in spite of the plastic wrappings. That strange juxtaposition, the informal relationship to the timeless, which still manages to stop you in your tracks is pure Vervoordt, and is exactly what he and his collaborators are trying to achieve again this summer with “In-finitum” in Venice, the coda to the trilogy.

Like the previous two shows, “In-finitum” will mix museum-owned works with pieces from Vervoordt’s own collection. “We discuss the theme first, instead of picking out showstoppers to work around,” he explains.

“We are about trying to find the imperfect … because we’re always trying to achieve perfection, but this is really more about infinity, making a pilgrimage to the infinite. The search is what is critical.” Beginning at the lowest level, the interior walls of the Palazzo Fortuny have been painted with muck from the Venetian lagoon, an idea first used in “Artempo” here two years ago, this time expanded also into the attic. There, “imperfect” takes on a larger meaning, as Vervoordt says he has put this highest floor together with “bad materials, cheap materials. Really low quality wood” covered in mud. The lower levels are described by Vervoordt as being about the “cosmos,” with pieces by Otto Piene, Angel Vergara, Fontana (who is ubiquitous in Vervoordt’s projects) echoing “that infinite feeling of the water.”

Visitors will then ascend, experiencing “emptiness … a void. This is religious to me. And what is religion? It’s that heavenly feeling. We tried to do this in Venice where you rise up to this huge attic and have what I hope is a sanctuary of silence.”

If all this seems slightly more mystical than a conventional art fair, it is because working in the 16th-century Gothic Palazzo Fortuny was for Vervoordt “really an evolution. Like he [Mariano Fortuny] is still living.”

“I worked as though I were consulting him on his own contemporary art collection.” Vervoordt is very good at identifying artists who seem to share his ability to reflect on and even try to capture the cosmic workings of time while speculating on our relation to it. Like Vervoordt, Fortuny was quite varied in his interests, which included painting, photography, and architecture, along with his better-known textile work; Vervoordt mentions how much he would “want to talk to him about ma.”

Ma, meaning interval, is the Japanese spatial concept that deals with the simultaneous experience of form and non-form, the intensification of the empty space between objects and places that generates its own palpable energy. Without explicitly saying so, this Zen aesthetic reigns in Vervoordt’s more personal design projects, and is a clear influence on “In-finitum,” from the title onwards, with that little hyphen signaling a pause that asks us to contemplate “the place in between … to ponder the magnetic field between objects. That void.” Bringing it back to a more concrete example, Vervoordt smiles, “Zurbarán and Cézanne do wonderful still lifes with that void.”

Marcel Proust, who described Fortuny dresses several times in his writing, also touched on the kind of ineffable intensity that Vervoordt carefully seeks out:

Of all the indoor and outdoor gowns that Madame de Guermantes wore, those which seemed most to respond to a definite intention, to be endowed with a special significance, were the garments made by Fortuny y Madrazo from old Venetian models. Is it their historical character, is it rather the fact that each one of them is unique that gives them so special a significance that the pose of the woman who is wearing one while she waits for you to appear or while she talks to you assumes an exceptional importance … ?

This idea of “exceptional importance” – a combination of history – time really – and a “unique” balance – that radiates out from a material object fits into Vervoordt’s approach more neatly than Proustian nostalgia.

In fact Vervoordt’s interest in Eastern philosophy and art has a kind of anti-nostalgia to it, which is blurred by the great age and rarity of so many pieces in his collection. Museums are big fans of his, and he has sold recently to the Metropolitan in New York, the Silver Museum Sterckshof in Antwerp, and even the Miho Museum outside Kyoto. According to Dercon, “Axel got a kind of green light in terms of the artistic milieu. Let’s say he became a kind of Sir Norman Foster of the art world. In any case, revered by some artists and feared by art dealers.”

Ambra Medda, co-founder and Director of Design Miami/Basel, tells me that Vervoodt’s “interdisciplinary crossover between art, architecture, design, and fashion relates to today‘s collector-cum-dealer-cum-curator … a new aperture toward how we can define ourselves to multiple fields in a number of ways.”

Vervoodt’s ability to glance in all directions at once drives his current curatorial interests. Not too long ago, Vervoordt became fascinated by the postwar Japanese Gutai movement instigated in the 1950s by Jiro Yoshihara. Yoshihara put out a manifesto in which he expressed his respect for the beauty of “art and architecture of the past that have changed their appearance due to the damage of time or destruction from disasters in the course of centuries.” It is the beauty of decay free from artifice, a looking backwards that does not have its judgment contaminated by homesickness or the ironies of a postmodern sensibility: that Sekhmet bust is perhaps more beautiful because it is damaged. While Vervoordt’s easy mixing of artistic periods, categories, and qualities feels both cozy and modern, his is a perspective that does not mock or distrust what belongs to a former time or a distant place.

Vervoordt’s real energy seems stored up instead in his stripped down “Oriental” drawing rooms, in contrast to the “perfect storm of material culture” for which decorating magazines like Interior Design celebrate him. The room on the first floor is justly famous, with pictures of it included in many of his published interiors books. Its current incarnation includes a floor-to-ceiling Antoni Tàpies painting from 1972 (“Well, I like big art”), ancient stone maitreyas, and a tall branch cut from the long rhododendron hedges just outside the front door, tucked into a standing vase behind the couch, which was already flowering from the heat indoors. However, there was a large empty quarter between the seats and the front windows, which threw the room slightly off kilter. Anne-Sophie Dusselier, who has worked closely with Vervoordt for the better part of thirteen years, also noticed it when she escorted me in: “How strange. There’s usually a Fontana bronze piece there. I wonder where it is now?”

It had in fact been moved up one floor, to the just-completed new Oriental drawing room. This one even more casual than the first, with a low ceiling, long futon cushions lining an elevated platform on one side, and the Fontana resting on another platform opposite, with a sort of gangway in between leading onwards to a bedroom. Both drawing rooms are naturally lit and pared down in terms of color, with washed-out, mottled grays and beiges predominating. The effect is both cooling and somehow clarifying to the eye, like a sun-faded surface that has assumed a kind of translucence. This is probably the point. These rooms hold fewer objects and paintings than the eclectic Wunderkammer downstairs on the bel étage, and the mind here is effortlessly directed wherever it wants or needs to go.

Vervoordt does not just sell this kind of quotidian curating, he practices it himself. Before settling down to speak at length in the original Oriental drawing room, he busied himself lighting a fire, changing the throws on the back of the couch, rearranging the cushions and generally fine-tuning the moment for maximum visual sophistication and physical ease – all part of a daily ritual of purification and resettling that occurs in the castle. Objects and artworks are constantly shifted and their powers reworked: moved from room to room, they regenerate that magnetism that keeps them vital. Yet the overall ambiance of the home remains the same. This is how Vervoordt tries to work with clients as well.

“I want to meet them first and find out what they are like, what their taste is. Take them around the castle and see what they like and don’t like. I don’t want you to come live in my home!” They spend time becoming acquainted, Vervoordt striving to craft a more refined version of the people he works with, to help them answer questions about themselves they might not even know they are asking: “I’m like a portraitist, and like a good portraitist I become good friends with those I’m painting.”

It is a personal connection to the project that he attempts, so that it becomes a reflection not of his desires, but of the person to whom it actually belongs. “The people who I work with, who can afford to redo their homes, maybe do not have as much money as before, but these are people who are still successful, who have accomplished something and are smart and interesting and want to express themselves somehow, maybe in a new way. That is why they come to someone like me. I have friends who are philosophers and scientists and many artists and we are always talking.” (Which I take at face value: his phone buzzes constantly, but he seems completely happy to ignore it.)

The recent record-setting auction of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé’s extensive set of art and antiques was a poignant reflection of this: Vervoordt counted the couple as friends and over the years had contributed multiple pieces to their collection. But maybe it was time for them to circulate again, disbursed like Vervoordt’s own peripatetic Fontana sculpture.

“You know, after September 15th when the markets crashed, I was fearful. I employ almost a hundred people. But right now business is more successful than ever.” Vervoordt believes this is because “Something is growing. There’s a return to this connection to the Earth, and I think people are trying to rediscover a new period in order to make sense of it all.” He returns to one of his mantras: “Antiques need to fulfill a contemporary need.” Their job is to orient you on a historical timeline, but also literally to be used. “You don’t want to totally restore things, you lose the energy. You can’t dream about them or meditate on them then.” Part of Vervoordt’s business is now concerned with the manufacturing of his own line of furnishings and fabrics – many of which are hand-woven – with upwards of 80 percent coming from within Belgium. “Antiques aren’t always comfortable,” he says, bouncing himself a little on the sofa cushion.

More than that though, a house decorated entirely with antiques or high art simply becomes a museum; a neutral space that is only about the objects on display. All of Vervoordt’s projects, however, are site specific, reaching towards that “new period” he is still attempting to define through collecting and exhibiting.

“Look at that rock over there next to the exquisite Buddha. It is a sculpture made by time.” This last idea is, of course, the guiding theme of the trilogy, summing up what Vervoordt has spent his life trying to communicate. “It’s about process” — whether that process is the bodily pilgrimage from the limbo-basement of the Palazzo Fortuny to its paradise-attic, or the chemical process of aging that creates the blistered, crackled effects on show throughout the castle and the exhibitions.

In a conversation with Jean-Hubert Martin, former director of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris who helped organize the first show, Vervoordt explained how “science has shown that in a cubic decimeter of air, which we perceive as empty, there is more energy than in any matter whatsoever. ‘Artempo’ is also about omnipresent time, the time that transforms and sculpts matter.” Pointing to the corner of the Oriental drawing room where a group of man-made and natural objects are assembled on a beaten, peeling 16th-century Italian chest, he says, “I wouldn’t care about that box if it was new or in perfect condition. It needs that patina to become interesting again. Oxidation — it’s an act of love really,” he grins confidently, wiggling his fingers in front of him. “Love between the object and the air …”