The Axis of Evil: Traveling to North Korea with ANDREAS GURSKY

In his State of the Union address in January 2002, George W. Bush condemned Iran, Iraq, and North Korea as an AXIS OF EVIL seeking weapons of mass destruction and sponsoring terrorism, setting off an unbreakable binary logic of either/or in world politics that still prevails today, five years later. What follows is a look at the murky atmosphere between the parameters of good and evil, of the known and the unknown, the true and the false. Andreas Gursky has penetrated the geo-political fortress that is North Korea, peering through its allusive – and illusive – cultural barrier only to in turn reconstruct his own still, singular image of the polished, choreographed social construction he saw there.

With Andreas Gursky in North Korea

Picture perfect: May Day stadium in Pyong-yang, the capital of North Korea. There, in the center balcony, under a ten meter-high portrait of the country’s founding father, Kim Il-sung, and surrounded by 90,000 North Korean soldiers in uniform, is a stranger: photographer Andreas Gursky, pushing vases obstructing the frame aside to get his cameras into better position. It’s his sixth time in the stadium, and he has worked his way up, step by step, to this hallowed viewpoint, from which he has the best possible perspective of the spectacle below: Arirang, a rhythmic gymnastics pageant with over 100,000 participants and the country’s largest mass event, one which has an immense impact on the entire North Korean people.

There are four flights to Pyongyang a week: two from Russia, two from China. At the Air Koryo gate in Beijing, young Americans are fooling around and taking pictures of each other under the Pyongyang LED screen to impress the folks back home. An Indian diplomat with a light blue United Nations passport is wearing a watch with two faces, each for a different time zone. A retired Sabena pilot wants one last flight on the aircraft he started his career on in the Sixties. A Dane collects the airplane safety cards from the back flaps of every seat. The other passengers are all Chinese or Korean – Northern and Southern. The North Korean government is making an exception to its travel restrictions due to Arirang and is allowing Americans and South Koreans to visit for the occasion. The music in the cabin is decidedly uplifting. Flight attendants with faces made up as white as porcelain – and with only eight flights a week, they may be the only ones in the country – are busy passing out sing-along sheet music with their white-gloved hands. We – friends of Gursky’s from the German art and film scene – are along for the ride. The aircraft is an IL-62 – IL, as in, illusion?

At the Pyongyang airport, we deliver ourselves into the hands of our guides: two interpreters and a driver. They will be sleeping in the room next to ours in the hotel. They will accompany us throughout the city, telling us about their country, translating, eating with us. Eating a lot. And drinking. Beers and shots. We hand them over our passports, tickets, and cell phones for the duration of our stay and let ourselves lean back and bask in the delights of not being free.

Arirang tells the story of Korea, a story that we are told time and time again on our trip, of its beginnings long, long ago, followed by a great, ahistorical leap into the 20th century – to the annexation by the Japanese, the Second World War, the division of the country, and finally, the establishment of a communist state in the north in 1948 by the great leader Kim Il-sung. Decades of growth. Years of famine in the 1990s. A happy future and a big dream of reunification. This history lesson is recapitulated at every monument, every drive through the city and, every evening, at dinner. With the possible exception of Israel, North Korea stands alone in deriving its identity out of the highs and lows of its history. Only in the case of Israel, it started 3000 years ago with the flight from Egypt. The North Koreans, on the other hand, only seem to draw from the events of the past sixty years.

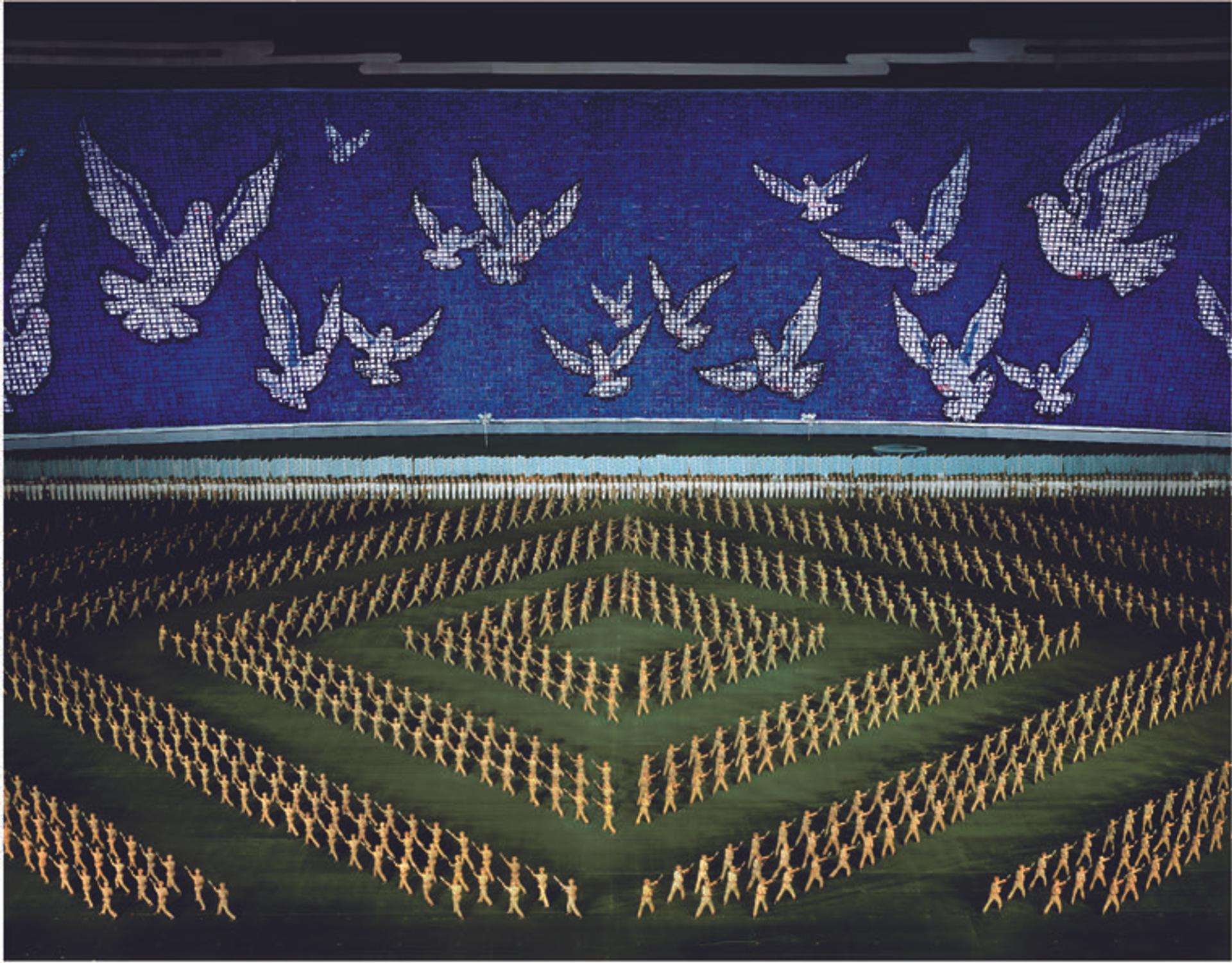

A giant hand rolls out a carpet of thousands of participants into the stadium. A collective turn and their color changes from blue to red. Another beat and the carpet becomes four separate squares, the squares become thin rectangles, like something out of a Hans Richter film, these become lines that finally come together as circles. We are watching the Asian heirs of Petipa’s ballerinas in Swan Lake, of Busby Berkeley’s extravaganzas. And sure, Leni Riefenstahl’s parades, too, in Triumph of the Will. The choreography is held together by suggestive, ultra-diatonic music on playback, and contextualized by the 200 yard-long images formed across the stadium, opposite the audience, by twenty thousand school children between the ages of 13 and 15 holding large, colorful books open on their laps to create enormous mosaics in Cinemascope. The images change with lightning speed, becoming an old Korean village, a racing buckboard wagon full of revolutionaries, a pistol, tractors, a dove of peace. To better show “the sunshine of the Korean people,” a few hundred children vibrate their books and the halo-like ring around the mosaic of Kim Il-sung glitters like gold. We watch these children leaving the stadium after the show and they are overexcited, exhausted, carrying big cotton bags for their books, worn from the months of drilling and the rehearsals, but above all very proud.

High above, from the dignitaries’ balcony, the event below seems almost two-dimensional – the participants and the background images melt into one. As always, Andreas Gursky is not satisfied until he’s found the spot from which the spectacle as a whole can become abstract, while maintaining the abundance of detail for which he is famous. After all, he has turned the stock market in Chicago into an all-over Pollock painting, a crowd of people at a techno rave into a Rothko cloud, and the race track at Bahrain into an abstract painting by Motherwell. And suddenly, Arirang and its 100,000 participants remind us of Gursky’s Rhine, made ten years ago. Three monochrome strips. A horizontal Barnett Newman.

Soft music plays at every landmark in Pyongyang – at the Kim Il-sung statue, at the monument to the 50th Anniversary of the Founding of the Party, at the memorial to the Victory in the Fatherland Liberation War, and even at the house where Kim Il-sung was born, a farmhouse 10 kilometers out of town. Everywhere we go, we are met by kind women in national dress who explain the monuments to us and tell us what to do. At the Kim Il-sung statue we buy flowers for two euros – foreigners never even see local currency – and rest them at the feet of the beloved leader. We learn, of course, that the statue is the largest bronze in the world, that Pyongyang’s Arch of Triumph is larger than the one in Paris, and that Arirang is the largest spectacle of all time – they like to boast in North Korea, and their nuclear program can also be seen in this context.

The most important monument in the city is Kumsusan Memorial Palace, the mausoleum of Kim Il-sung, who died in 1994. Our escorts abruptly push aside a group of Koreans waiting in mourning clothes and lead us into the side wing of the palace. For twenty minutes, we glide on stainless steel moving sidewalks, painted red and embedded in white marble, towards the main building – which gives us plenty of time to compose ourselves for our meeting with the beloved leader. Mourners head toward us and take plenty of time – and this seems to be a part of the overall stage direction here – to let what they’ve just experienced sink in. No one says a word, no one moves, no exchanges of glances. What follows is a succession of purification and security stops: foot brushes, x-rays, metal detectors. We finally enter a long dark room and think we’re there. But the architects have built in yet another delay: an anti-chamber, at the end of which we are welcomed by a marble statue of Kim Il-sung, backlit and silhouetted in front of colored light. Here too, the soft music.

Before we’re allowed to enter the main chamber of the mausoleum, after being disinfected in a wind tunnel, we receive specific instructions. As we had already been told the previous evening, we need proper clothing – dresses for women, neckties for men. Now we have to file into a long line to step in front of the embalmed corpse. “Bow briefly, don’t linger, and walk away.” We try in vain to conform to the pace of the Koreans, taking measured steps, fluidly, without looking to either side. But we can’t. We’re so individualistic that we’re disoriented. We loiter, with no idea what to do with our limbs. The room is filled with a hushed, not immediately identifiable sound: the soft sobbing of Korean women lamenting the loss of their beloved leader. Is this staged, too? For us?

North Korean paranoia, in which nothing can be as it seems, is mirrored in the paranoia of the foreigners. We suspect every pair of well-dressed lovers we cross of being extras in the grand staging of a happy, prosperous country. Shouldn’t we, instead of trying to find the North Korea that eludes us, be looking at the North Korea that is there? The magnificent façades, the bravado, the vanity we encounter, it all has a poignant side as well. As opposed to arrogance, a characteristic shared by all Western statesmen, vanity desires recognition from its beholder, and shows a certain respect and reveals a certain vulnerability in return.

Gursky uses 100 ASA Fuji film in two large-format Linhof cameras that are positioned side by side, one with a slight wide-angle lens, the other with a standard one. Exposure time: 1/8 of a second, f-stop 5.6 to 8. He needs this for depth of field, and the relatively low speed film for the resolution. Any occasional blurred movement is discarded later in the process. And he gains speed by underexposing the film stock one f-stop, and has it developed using push processing. He has to know the performance‘s sequence of events well in advance to know when the short motionless moments that he needs are to come. He transports his equipment in a small, elegant Louis Vuitton suitcase. In the cool fall weather he wears a blue wool cap from Prada, which he bought at the mall of the Peninsula Hotel, Beijing. The Koreans are not cold in their short-sleeved shirts.

Andreas Gursky’s fame and financial success have given him the chance to get to know and love luxury, but he’s still old-school enough to lug his equipment around, drink with the best of them, make do with only a few hours of sleep in a night, and stay in cheap hotels. When loading and unloading film, he barricades himself in a bathroom or closet and we hold a mattress up to the cracks to keep out the slightest bit of incidental light. The cold constructor of vast panoramas, whose lavish productions are always distilled into one or two pictures and whose catalogue is correspondingly sparse, turns out to be a truly passionate picture-taker. He snaps pictures everywhere he goes, always on the lookout for locations and ideas for a piece. “It would be nice if I could get around to simply capturing landscapes on film again,” he says.

Nothing in North Korea is allowed to go wrong. Our chaperones do everything they can to facilitate our wildest desires and deviations in our itinerary even if that means long telephone conversations with “the company” and hectic, behind-the-scenes reorganization. They make everything possible – as in the Royal slogan, “Never complain, never explain.” Does the little bit of meat they try to pass off to foreigners as abundance have to be raced to another restaurant just because we, on a whim, change our plans? There it is again that mutual paranoia. But this time, our change in restaurants is worth it. After a barbeque, the pretty waitresses in their pink dresses, white aprons and name tags go on stage and sing. Artificial sunflowers on stage left and stage right, a keyboard and a blue set of Yamaha drums at center-stage. They sing Santa Lucia, O Sole Mio and Arirang. It’s so bizarre, so camp, and so David Lynch that it‘s almost too much to handle.

It’s pitch dark during the Arirang sequence dealing with the annexation by Japan. A solitary spotlight breaks through the darkness and a star rises: the great leader Kim Il-sung. Applause. The simplicity of North Korean history, which even foreigners absorb in a very short time, makes identifying historical segments distressingly easy. After only a few days, just a mention of Paektu, the holy mountain where Kim Il-sung had his vision of the future of his people, brings tears to our eyes. It is almost impossible to imagine the extent to which this myth has become embedded in the consciousness of the North Koreans, who have heard nothing else since their childhood. Those who could tell another version are long dead. Press, television, and books are all censored. Access to the Internet was canceled after a short trial run in 2004. People aren’t allowed to travel or phone and the few foreigners who visit the country have as good as no possibility to talk to the people. And even if we could, is there really such a great difference between the “people” at large and our guides? Does our Western assumption that the oppressed masses are on the verge of rebelling – only held back by true believers like our chaperones – actually correspond to the reality of the situation? There’s certainly dissatisfaction with the unjust distribution of the little food they have and the privileges of the elite, but a revolutionary consciousness, a realistic alternative – where would it come from?

Despite its optimism, Arirang is a sad story, one to move even sophisticated Westerners. Especially us Germans. It is the story of a separation. Rirang, a young man in mythical times, goes on a journey and leaves his beloved behind. A rich rival courts her but she remains faithful to her true love. Rirang returns, sees her with the admirer and leaves her. “Ah, Rirang!” she cries out after him. Today, Rirang is the south and the north the spurned beloved. The longing for reunification is the bitter counterpoint to the North Korean success story we hear everywhere we go. Maybe it’s even an openly kept emotional outlet for a people otherwise brought up to have no wishes. As opposed to the GDR, here it is the country’s foremost official priority. There is a monument to reunification, there is Reunification Road, the road from Pyongyang to South Korea. In 1980, Kim Il-sung came up with a visionary multi-stage plan. The reunification had to happen independently, without the interference of foreign powers and peacefully. It would initially be the Democratic Confederation of Koryo – the country’s former, politically unencumbered name – in which the two systems could co-exist. It would have open borders and Koreans in both countries would be able to decide in which system they would rather live. Further planning is not yet possible, he concluded shrewdly. But that doesn’t mean it’s unattainable: “The last step will be the task of a future generation.”

At the end of Arirang, the gymnasts form the outline of the Korean peninsula in the middle of the stadium. They are dressed in light blue, the color of the pan-Korean table tennis team, which was allowed to represent both countries for the first time at the Olympic games in Athens. The Koryo flag will also be light blue. Finally the 20,000 school children produce a new mosaic: “We must be the ones to open the door to reunification.” As I was with the invisible stage direction that seems to permeate North Korea, Andreas Gursky is unsatisfied with reality as he encounters it. The many hundred exposures of Arirang are the raw material he will use to make his single image. Back in his studio, he will make large blow-ups of the best shots and immerse himself in them until the first montage possibilities present themselves. “That strip between the field and the background disturbs the homogeneity,” he says. “I want a flowing transition. Every square inch of the picture has to be justifiable.” Computer layout sketches will follow, and finally, the protracted work in the lab with a technician. Various chronological phases of the performance are combined and irritating elements are removed. Gursky works like a film director who condenses documentary footage in the editing process and paradoxically, by means of manipulation in addition to his personal contributions, actually increases and enhances the picture’s authenticity. Only with Gursky, the result is a single – and singular – image.

Individuals cannot achieve the perfection we witness with Arirang. These aren’t performers in a stadium, they are metal shavings being aligned by a magnet. The individual gives up his or her individuality – in this society as in its symbol, Arirang – and subordinates it to the collective as personified by Kim Il-sung. They are all his children, clay for the great sculptor. In the mass gymnastics, each individual is intended to physically experience him or herself as a minute part of a whole that is far greater than their mere individuality. And it is true that if only one gymnast turns in the wrong direction, the larger picture is marred. As such the aesthetic is in essence anti-individualistic: this artwork can only come about if I give myself up for it. The moment I resist, the moment I become recognizable in the sense of the modern aesthetic dogma of resistance, the work in the making is destroyed. Only in failure do I reveal my individuality. And my individuality determines how I fail. Only failure is mine. Like in music, when conductors lose themselves in their music, consummate performances by Bernstein, Carlos Kleiber or Celibidache become, in that aesthetic sense, the same. But when their performances aren’t perfect, their individuality shines through. Bernstein becomes sentimental, Kleiber hectic, and Celibidache didactical. But as long as they’re perfect, those characteristics are imperceptible.

“I never claim the picture is a depiction of reality,” says Gursky. “It’s always a combination of invention and reality, an interpretation of reality. The impressions in your head get mixed up after one and a half hours of Arirang. A picture is not good because its subject is good, but because something has been made discernible, something that gives the picture direction. But I never give up the link to the documentary aspect of it.” What happens when North Korea’s stage direction collides with Andreas Gursky’s? Maybe the product of two negative integers is positive this time around, resulting in the most authentic depiction that can be made of North Korean reality today.

Back in Germany, we sit down to watch Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain, which was shot in 1966, in the middle of the Cold War. Hitchcock’s East Germany is today’s North Korea. Pyongyang is not exotic geographically, but time-wise. We never had the feeling that we were in a faraway country, east of China. Everything seemed familiar, like a faded memory, suddenly brought back. North Korea has no famous cultural treasures, no Angkor Wat, no Forbidden City. It is a world parallel to ours. And that, today, is truly exotic. What Hitchcock really got across in Torn Curtain is how the American scientist, played by Paul Newman, felt in East Berlin. The friendly employees of the Ministry were always present; they had always already brought his luggage to the right place and reserved the right table. “Our company,” was the term used by Mr. Park, one of ours guides in Pyongyang, who also checked us in for our departing flight, gave us our cell phones back, and collected our hotel keys. Everything is taken care of because everything is connected to everything else. Because it’s all one organism. “Our company.” It doesn’t take much getting used to. As one of Germany’s wealthiest businessman once wrote, at the end of a book about his kidnapping, “When life gets too hard and the difficulties make it seem like it’s not worth living, the wish can arise to have a chain around one’s ankle again and to be back in a small room that one knows far better than the world outside.”