Cognitive Capitalism: NEIDICH, DENNY, POPESCU, HARNEY and NDIKUNG at the SFSIA Berlin

In 2004, the French economist Yann Moulier Boutang coined the term COGNITIVE CAPITALISM to describe the way labor has shifted from the manual to the mental, and correspondingly, our cognition – our very thoughts and emotions – has been invaded by the commodifying logic of capitalism. Cognitive capitalism was the theme of this year’s Saas-Fee Summer Institute of Art, or SFSIA – in its own words, a “nomadic, intensive summer academy with shifting programs in contemporary critical theory,” founded by the conceptual artist and theorist Warren Neidich in 2015. Over the course of three weeks in July, students and speakers discussed a dizzying array of concepts relating to the parallel changes in the technological, the economic and the cognitive.

A guiding premise of the SFSIA is that certain issues cannot be investigated while staying within the hard disciplinary borders that remain enshrined in universities. This was reflected both in the sheer diversity of the faculty, and in each individual’s refusal to stick within the traditional boundaries of their fields. In between the talks and seminars, I sat down with five members of the faculty – an eye surgeon turned artist, an engineer turned curator, a philosopher turned entrepreneur, and a start-up obsessed artist – to talk about cognitive capitalism and the role of education in facing its challenges.

Fourth Way Silhouette Jenga Display Prototype 2017 Laser-cut Jenga XXL cardboard blocks, plexiglas, texts distilled from Max Harris’ THE NEW ZEALAND PROJECT 190 x 70 x 70 cm Photo: Nick Ash

Warren Neidich

Warren Neidich began working on neuro-aesthetics in 1997, launching artbrain.org and the Journal of Neuro-Aesthetics. Besides his training in photography and architectural theory, he has a background in neuroscience and has worked as an eye surgeon.

Let’s start by talking about the central topic of the summer school. What constitutes capitalism’s becoming cognitive?

The mind and the brain are the new factories of the 21st century. We no longer work on assembly lines, producing things with our hands; instead, we work on various platforms on the Internet. There is a term for this new precarious class: it’s called the cognitariat. We are constantly producing data through searching and communicating online. That data, is crucially important to the way that feelings and emotions have become commoditized, all the while creating huge profits for the corporate elite.

The idea of cognitive capitalism is generated by the thought that the brain is not simply inside the skull but is also external to it, consisting of social, cultural, political and technological networks that are constantly evolving. These changing conditions in the world are recorded and activate changes in the mutable architecture of the brain – in a word, neuroplasticity.

What was the motivation behind founding the summer school?

When teaching, I found that some of the basic questions that needed to be talked about in art schools remained unaddressed. I found that the students’ lack of interest in theory had a lot to do with the fact that what was taught no longer represented their world, or helped them to understand it. Canonical theory, especially the French School, was no longer radical but became a kind of sovereignty that subsumed aesthetic production and became a counter force to the production of experimental artworks.

Each generation creates artworks that disrupt the socio-cultural and aesthetic field. Those disruptions become the new data for creating theory, challenging philosophers and artists to reinterpret the world with new terminologies. So theory is generated from artistic interventions. On the other hand, theory is a material like paper or editing software, it is the raw material with which artworks are conceived and produced. Theory can be used as a medium for the production of art in the broadest sense of the word.

Where do you see the challenges for education in art and philosophy in the future?

I think the most important challenge for theory and art in education today is the emergence of populism and right wing governments. What we see in the U.S. with Donald Trump, in Italy, Hungary and Greece, creates an atmosphere that is very hostile to theory, which is genuinely dangerous to right wing governments. We need theoretical frameworks to be critical of these developments and to create new forms resistance. This already has taken place through feminism and post-colonial theory. We need to understand that the new right is already using the attention economy and digital analytics through social media to create a form of bottom-up propaganda of which fake news is an example. These new technologies and their platforms have allowed governments to renew their assault on a women’s rights as well as inciting the racist imaginary. My new works The Glossary of Cognitive Activism (2019) and Pizzagate Neon (2018), currently on display at the Venice Biennial, are attempts to expose the new apparatuses at work in the digital economy and raise consciousness about the new digital sovereignty that threatens our freedom.

Founders Board Game Display Prototype (Detail) 2017 Customized “Settlers of Catan” game pieces, 3D print, UV print on Butler Finish Aluminium Dibond, UV print on card, LEDs, molded electronic wiring, Dell PowerEdge 1950 server casing, Linoleum, MDF, powder coated steel, Plexiglas 120 x 103 x 103 cm Photo: Nick Ash

Simon Denny

Simon Denny works as an artist, an exhibition maker and a teacher, reflecting on the social and political implications of start-up culture, emerging technologies and cryptocurrencies. After studying in Auckland and Frankfurt, he settled in Berlin. When we touched on the intersection of art and business, he described the feeling of having “larped” as an entrepreneurial artist for several years, playing with a Warholian stance on art as business. This lead to aesthetic overstatements of tech culture, such as exhibitions that looked like trade fairs.

The acceleration and complexity brought about by cognitive capitalism and tech start-up culture is something you reflect in your installations and sculptures. How can storytelling help to navigate this complexity?

Narrative has become very interesting to me. I think there is a viscosity to the rhetorical and discursive space of the now, it’s just thick with narratives. Often it is difficult to parse one from another and find every message’s ontology, in the sense of understanding what it goes back to and whom it is speaking to. Part of my encounter with Silicon Valley tech culture was about trying to understand what it was politically and unpack all this rhetoric, coming from another discipline with different values and perspectives. I tried to play with competing narratives in order to replicate and unpack this complexity.

Something I struggle with in my work is how to highlight narratives which are helpful to understanding things, without either simplifying or getting lost in the details. Now, after a period in my work that went very baroque and maximalist, I’m heading towards something more succinct. Reflecting complexity, and how it overwhelms us, has reached a point of saturation, and is less effective than it used to be. Perhaps what the world calls for right now is more clarity, focusing on things that are important.

What role does interdisciplinarity take in your practice?

I have gotten a lot from talking to business people and technologists as well as reading social sciences and anthropology. My interest is more broad than just the sciences, but I definitely believe that for me as an artist it is important to be informed and literate. I am generally curious, and something I learned at art-school is to look beyond the discourses one is immediately surrounded by. While I was in Frankfurt, I became interested in arts practices from the 70s that looked at cable TV and connected them to media theory. That’s what led me to my longer arc of interest in people from the California tech sphere and art that spans counter culture and cyber culture. Reading broadly is something I also encourage my students to do, and this includes looking beyond aesthetic discourse. Often this bleeds into practice, which tends to make things more interesting.

Game of Life: Collective vs Individual Board Game Display Prototype 2017 Customized Das Spiel des Lebens game pieces, 3D prints, UV print on Butler Finish aluminium Dibond, UV print on card, customized LED lamps, molded electronic wiring, Dell PowerEdge 1950 server casing, Linoleum, MDF, powder coated steel, Plexiglas / UV print on canvas 105 x 103 x 103 cm Photo: Nick Ash

Adina Popescu

The philosopher and futurist Adina Popescu works in VR and immersive storytelling. She is interested in nature conservation, biomimicry and the potential of tech to create bottom-up movements. Adina’s latest project is the Æerth platform, which features a virtual model of our planet, offering a crowd-sourced climate and environmental impact model where people can organize towards solving climate-related challenges. She is an advocate of Web3 applications, which use the decentralizing potential of blockchain to create a more democratic Internet and challenge big data monopolies.

How have the changes in capitalism over recent years influenced your work and how do you keep up with the acceleration of knowledge circulation?

Living in a bubble like San Francisco or LA can make people overemphasize their careers and go nuts about getting ahead and competing with each other. They start losing sight over the important things in life. Berlin still allows me to develop a vision from scratch, and to take the time to do so. By thinking of ourselves and of our work as a commodity from the get-go, we may not be able to create something that is truly novel and unexpected. Instead we will always remain within the context of what is already considered as “successful” or “cool.”

A lot of programmers and people working in tech are starting to use this pill dubbed the “limitless drug,” just to be able to focus for 16 hours a day in order to stay ahead. I doubt that creating paradigm shifts could come from that. At the same time, knowledge production is going up exponentially – so the question is, which cultures will be left behind in this competitive market model?

You have been a philosopher, an artist and an entrepreneur, working across disciplines and institutional boundaries. What does education need to keep up with current conditions of cultural production?

We need more state funded think tanks. We need to offer students labs by providing the future tech needed for them to innovate, and to bring people together across disciplines. The private sector is developing much faster than state institutions. In Europe we hold the latter to a high standard, as they traditionally provide a safe space for people to innovate, to teach and to do their research independently. Their demise is unfortunate. Right now the groundbreaking research is happening at Google X or MIT instead of public institutions, so Silicon Valley gets to monopolize intelligence.

Our kids nowadays are mainly being educated via the Internet. But the Internet is not neutral: the sites that have the most traffic are mainly US sites, such as Amazon, Google, Facebook, and Instagram. This leads to a wide adoption of US values in Europe. I am not saying that I am against it. It is just important to acknowledge that the Internet is not neutral – which is why the update of Web.2.0 is long overdue. Web3 will be shaped by its international users, no matter where they are, and not by the monopolies controlling it. I am always for diversity and competition; what we are seeing right now is the opposite. Berlin, especially, has a long-standing tradition in decentralized peer-to-peer networks. We should use the intelligence that is here, instead of trying to replicate the US model.

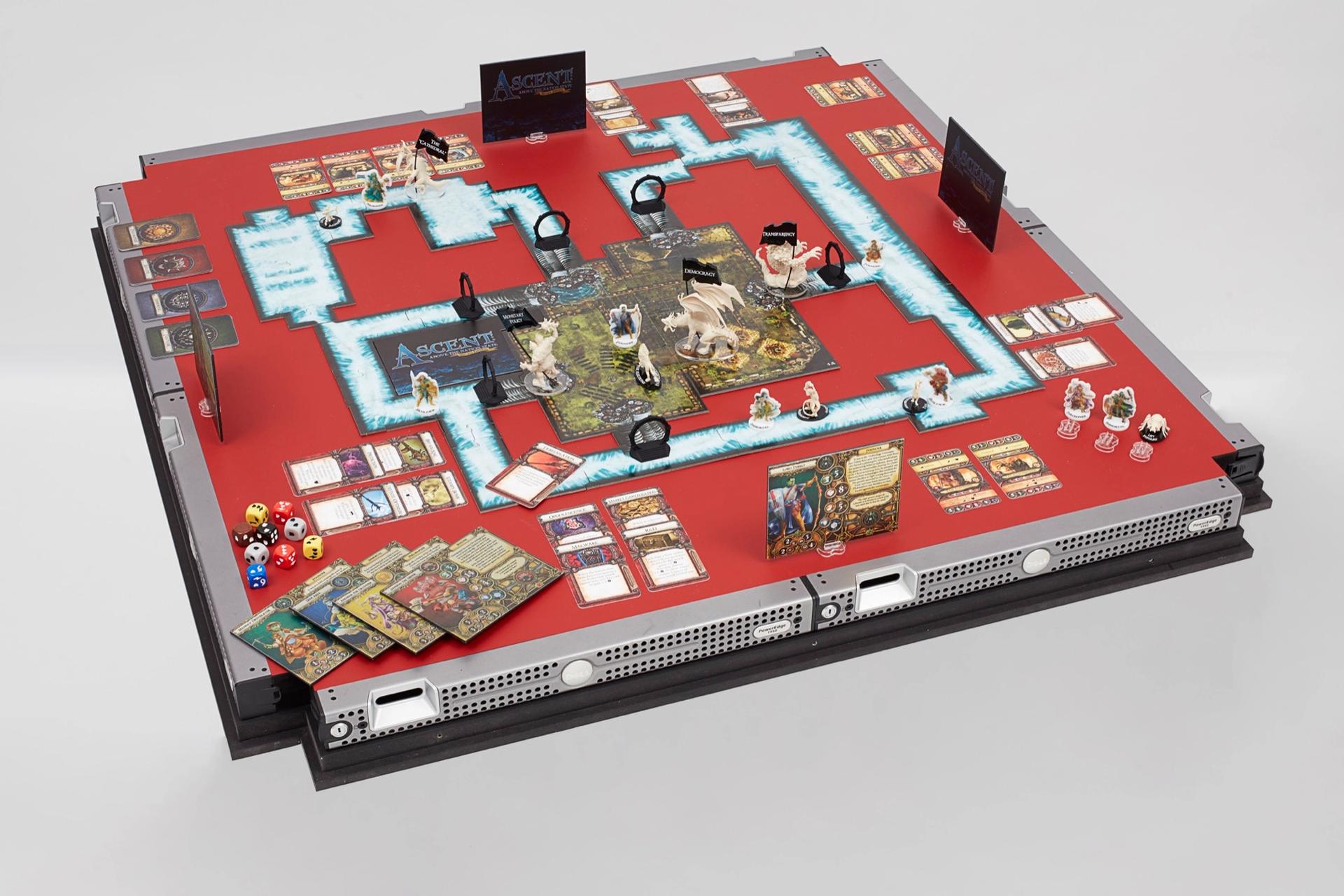

Ascent: Above the Nation State Board Game Display Prototype (Detail) 2017 Customized “Descent”– Journeys in the Dark” game pieces, UV print on Butler Finish Aluminium Dibond, UV print on card, LEDs, molded electronic wiring, Dell PowerEdge 1950 server casing, Linoleum, MDF, powder coated steel, Plexiglas 105 x 103 x 103 cm Photo: Nick Ash

Bonaventure Ndikung

The curator and critic Bonaventure Ndikung has a background in biotechnology and medicine. Before he committed full-time to his curatorial practice, he worked as an engineer for several years. The notion of the laboratory is something that connects his work as a scientist and a curator: in 2009, Bonaventure founded SAVVY Contemporary – The Laboratory of Form Ideas, where experimental research and exhibition formats take place side by side.

What is missing in the discourse of cognitive capitalism?

There never was a capitalism that excluded cognition. A working body is always a cognitive body, a thinking body. Supposing that labor has become immaterialized ignores the fact that more and more industrial labor is outsourced to countries outside of the West. Cognitive capitalism’s smartphones and data centers heavily rely on manual labor conducted under the worst conditions. People who are mining coltan and other metals necessary for the production of electronic devices face much worse conditions than those who develop algorithms in Silicon Valley. The same goes for the assembling of iPhones and other devices in Asia. Another issue is the afterlife of computers and smartphones. They don’t just disappear, but, for example, go to dumps in Ghana instead, where eight or nine year old children have to go through the trash to pick up bits and pieces in order to sustain themselves. Any current critique of capitalism needs to take these conditions into consideration.

What challenges does cognitive capitalism imply for education in art and the humanities today?

The most important question to ask is about the curriculum. Who teaches what, when and where? In order to change thinking, we need to work on the curriculum. The division between arts and sciences, itself a leftover of the capitalist division of labor, needs to be questioned. The fight against capitalism is a fight against disciplines.

Stefano Harney

Stefano Harney works mainly as a teacher and a writer. Until recently, he taught strategic management at Singapore Management University. In 2013, he published The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study with Fred Moten, adopting an anarcho-poetic approach to studying and the subversiveness of informal life within institutions.

How has the proximity to business studies influenced your theoretical approach?

This mainly happened in two ways. Firstly, working with business schools made me refine my ability to talk about my ideas with people that have not had a lot of exposure to theory in general and maybe have never even heard of Marx or Freud. The second thing is that it made me realize the theological character of business studies and their connection to racial capitalism. The implications of improvement, measurement and accountability, the distinction made between the productive and the unproductive, is essentially a continuation of a racial sorting machine. The very notion of who is productive, efficient, developing, capable and who isn’t is fundamentally flawed and dangerous.

In the seminars we talked a lot about the connection between colonialism and the philosophy of enlightenment, unfolding the disastrous implications of classic notions of property. What role does cognitive capitalism play for providing a critical understanding of property today?

Fred [Moten] and I were trained in the black radical tradition, which draws from the writing of Cedric Robinson among others, the history of black movements and black thoughts, and which proves an embodied critique of the notion of property, individuality and ownership. Cognitive capitalism presents some opportunities to develop this critique because of the introduction of a number of more collective understandings of how cognition and affect might operate. However, the strong interest that cognitive capitalism has in the individual mind is something we regard as necessary to interrogate. The individual mind, as a construct of European thought, has never been attributed to all members of the human species, which is a problem that needs to be taken into consideration. We prefer the strains of cognitive capitalism that take us out of the individual and away from the mind towards the concept of the general intellect.