Doing Donuts in the White Cube with Renegade Minimalist OLIVIER MOSSET

The Swiss visual artist Olivier Mosset originally became a biker after a gang of Maoists gathered near his studio. Seduced by the hum of liberty and leftist foment – this was on Paris’s Rue de Lappe after the uprisings of May 1968 – biking granted the young minimalist and Daniel Buren co-conspirator access to a new material and social world. At first, biking was a counterlife to art, but the aesthetic quality of the object made itself felt in his work. In 1974 Mosset bought a 47” Shovelhead Harley-Davidson, a bike he rode to exhibition spaces across Europe, photographing it to use on invitation cards the way Le Corbusier took pictures of his car outside newly finished projects. In both cases, vehicles were symbols for technological modernity but also the possibility of progress. For Mosset, they became an aesthetic wormhole, a means of pushing and escaping the limits of art.

Motorbikes act as timestamps in Mosset’s career. After leaving Paris for New York in 1977, he acquired another Harley: a 900cc 1969 Ironhead left in storage by François de Menil, architect of the Rothko Chapel in Houston. The first bike he presented as pure art – a readymade without the necessary papers for road use – was a 74” Panshovel featuring a Jackson Pollock “drip” pattern on its tank and rear fender. Rolling the machine indoors was an invasion of the hermetic white cube, collapsing the distinction between gallery, studio, and workshop. The art hog was a pivot in Mosset’s personal collection, meticulously catalogued in Wheels,accompanied by essays, interviews, and a rich spectrum of archival photography from the 1960s to today.

Olivier Mosset showing his Jackson Pollock "drip" tattoo by the American artist Alix Lambert.

“Except for the protective gear you’re wearing, there’s nothing between you and the rest of the world,” wrote Honda Blackbird rider John Berger in Keeping a Rendezvous (1992). “The air and the wind press directly on you. You are in the space through which you are travelling.” When Mosset relocated a third time to Tucson, Arizona in 1996, the space he occupied was suddenly warm, dry, and perfect for daily biking across vistas that appeared as though plucked from the epic landscapes of the Hudson River School. He began collaborating with the artists Vincent Szarek and Jeffrey Schad, complimenting early works in abstract painting with large shaped canvases that recalled the lonely billboards that line even the longest American highways. Szarek worked in an auto body shop before attending art school and incorporates a highly-skilled air spray technique as part of his practice. The trio also worked on cars: mainly vintage Chevrolets, in homage to Louis Chevrolet, born a mere 10 miles from Mosset in Switzerland, who made a parallel migration first to Paris then across the Atlantic to found the Detroit-based Chevrolet Motor Car Company in 1911.

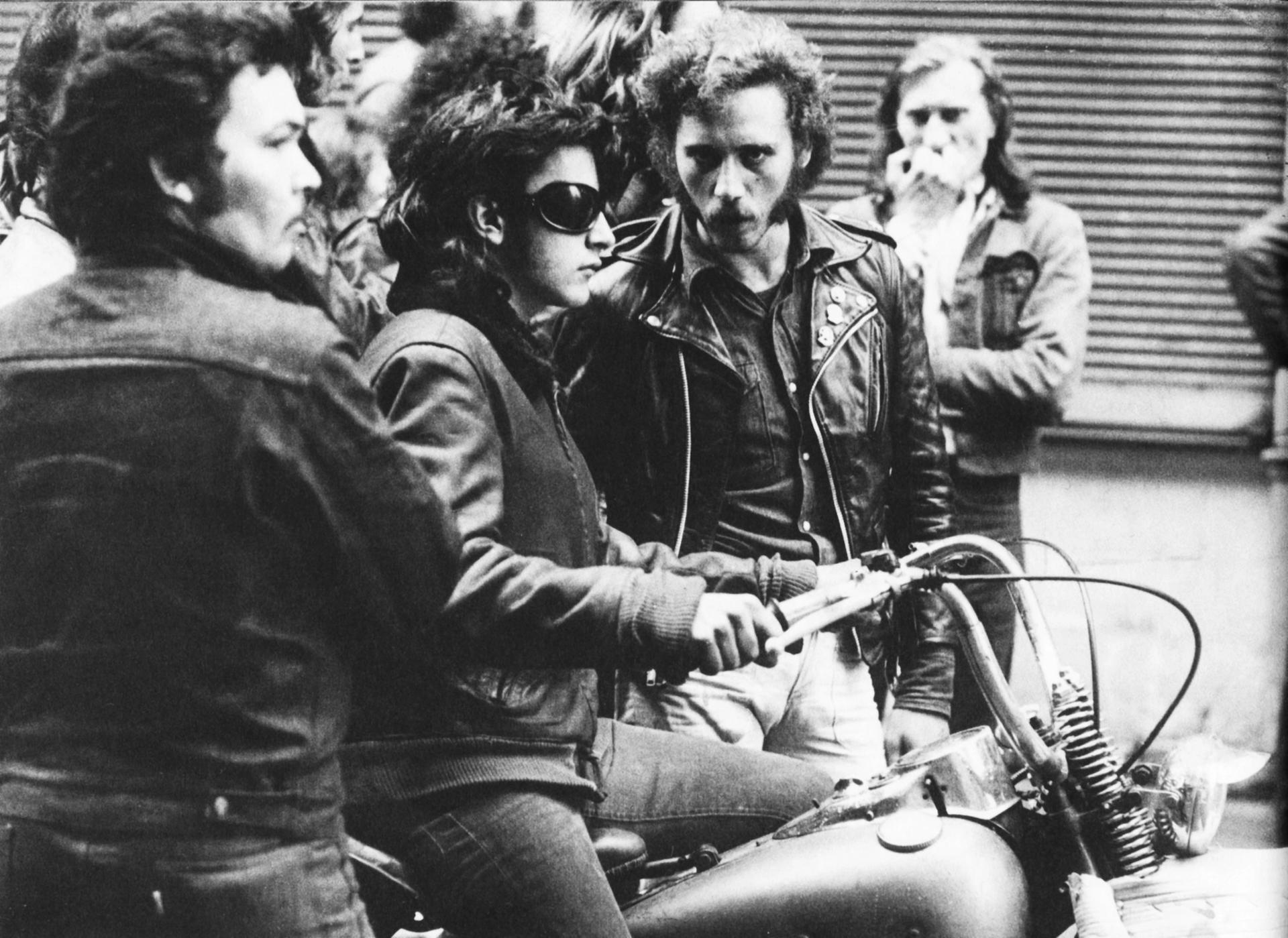

The opening of solo show by Mosset at Galerie Mathias Fels & Cie., Paris, France, 1971.

The art historian Philip Ursprung suggests “total urbanization” as Mosset’s ultimate theme. Parking lots, desert highways, the “boneyard” of decommissioned airplanes near Tucson – totems of industrialized society that stretch across the desert, a creeping totalism for which bikes are perhaps the most extreme metonym. Where else is the sensual rush of speed machines so closely linked to human frailty — the signs and symbols of a rebellious vernacular culture interchangeable for instances of high art? “I still believe that a painting or a ‘chopper’ is saying something,” Mosset says, “either you get it or you don’t.”

Wheels is published by Edition Patrick Frey (Zurich, 2018).

This article originally appeared in 032c Issue 34. Olivier Mosset’s Untitled (2018), will be on view at MaMo Marseille until September 30, 2018.