ETTORE SOTTSASS: The Master of “Bastard Design”

This article was taken from 032c Issue #27, “Raf Simons.”

At times utopian, at times hedonistic, the work of Ettore Sottsass (1917-2007) can best be described by its light touch. As the designer himself once said: “If you have to tune into something as soft as history, there is no way you can do it using harsh measures.” A prisoner of war during WWII, Sottsass lived through hopes of postwar reconstruction, the illusions of industrialization, and the uncertain advent of the electronic landscape. It seems as if history had educated Sottsass as a cosmically detached filter of perception, a visionary who could help cool down events.

A drawing by Sottsass.

The Factotum bookcase. designed in 1980.

Wolf House, Colorado, USA, 1986.

Esprit showroom, Hamburg, 1986

Esprit showroom, Cologne, 1986

Elledue bed for Poltronova (Mobili grigi), 1970

A glass piece for Ernest Mourmans, 2006

Sottsass lopunges in India, 1988.

Ettore Sottsass during World War II, circa 1944

Sottsass developed an interest in photography and painting before taking on practices in ceramics and industrial design. He considered himself an architect who made furniture. He also considered himself a product designer who made buildings. He found it easy to glide past the boundaries of genre, working to add an expressive layer onto the hyper-functional surfaces of modernism.

During his long partnership with the Italian manufacturer Olivetti, Sottsass defined a role for himself as a poetic agent of industry—a creator who operated in the spectrum between art and commercial manufacturing. Unlike his German counterpart Dieter Rams, whose work paid homage to Braun’s engineering, Sottsass approached design with a humanistic eye for what objects can communicate.

When asked by Olivetti to design Italy’s first computer in 1959, below, Sottsass set out to create a machine that accentuated the occult mystery of an unfamiliar technology. What resulted was the Elea, a mammoth console housed in polished aluminum that created a ghostly reflection of the operators who tended to its circuits. Sottsass’s design projected a certain drama – a feel for the fantastical – that became a defining feature during the advent of the electronic landscape.

Ten years later, Sottsass carried this energy over to his iconic red portable typewriter. The Valentine was an alluring anti-machine. It was designed to be used anywhere but the office, in the unformed frontiers of the everyday. An object centered on personal empowerment rather than the glorification of function, the Valentine typewriter presupposed the pop verve that has come to surround today’s consumer electronics.

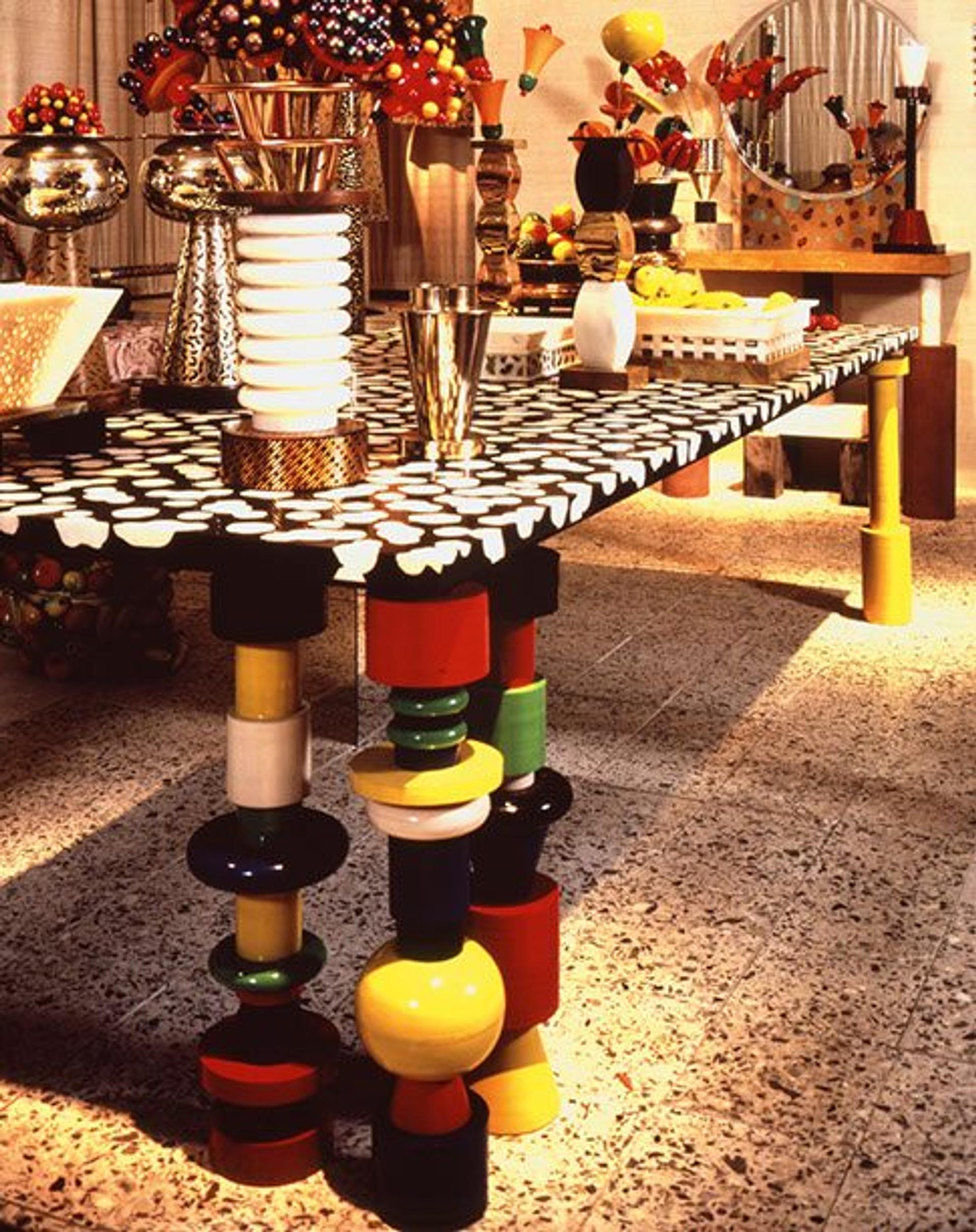

Sottsass’s radical break with Olivetti and industrial design came in the form of Memphis. Heralding itself as “The New International Style,” Memphis’s refreshingly chaotic vision turned into a success that transcended design. It captured a moment in thinking, an impulse to graft something heterogeneous and counter-rational onto the unflinching mold of modernism. Sottsass described Memphis as a “boiling cauldron of mutations” that produced “bastard objects” through a style that traversed metaphor and utopia. It was an experiment that dared to flirt with kitsch and pastiche, freely colliding styles and transporting vernacular materials such as plastic laminate from the kitchen to the living room. It is a style that is now ubiquitously invoked in today’s design, from textiles to objects. Yet as is usual with such cases, the imitators tend forsake the inventors. After all, when introduced to the public in Milan in 1981, Memphis was so iconoclastic that it incited an actual riot.

Images taken from Sottsass, published by Phaidon, 2014. This article was taken from 032c Issue #27: “Raf Simons,” more issues available from the 032c store.