GALINA BALASHOVA: The Artistic Director Behind Four Generations of Soviet Spacecraft

Can intimacy exist in a vacuum?

When architect Galina Balashova was commissioned to devise the interiors of Soviet space capsules, she was given a futurist-design dream. Without the limitations of gravity – with no up or down – architecture could be freed from earth-bound requirements such as a ceiling or floor. Yet Balashova had the visionary insight to realize that the mind has its own internal gravity, a craving for familiarity.

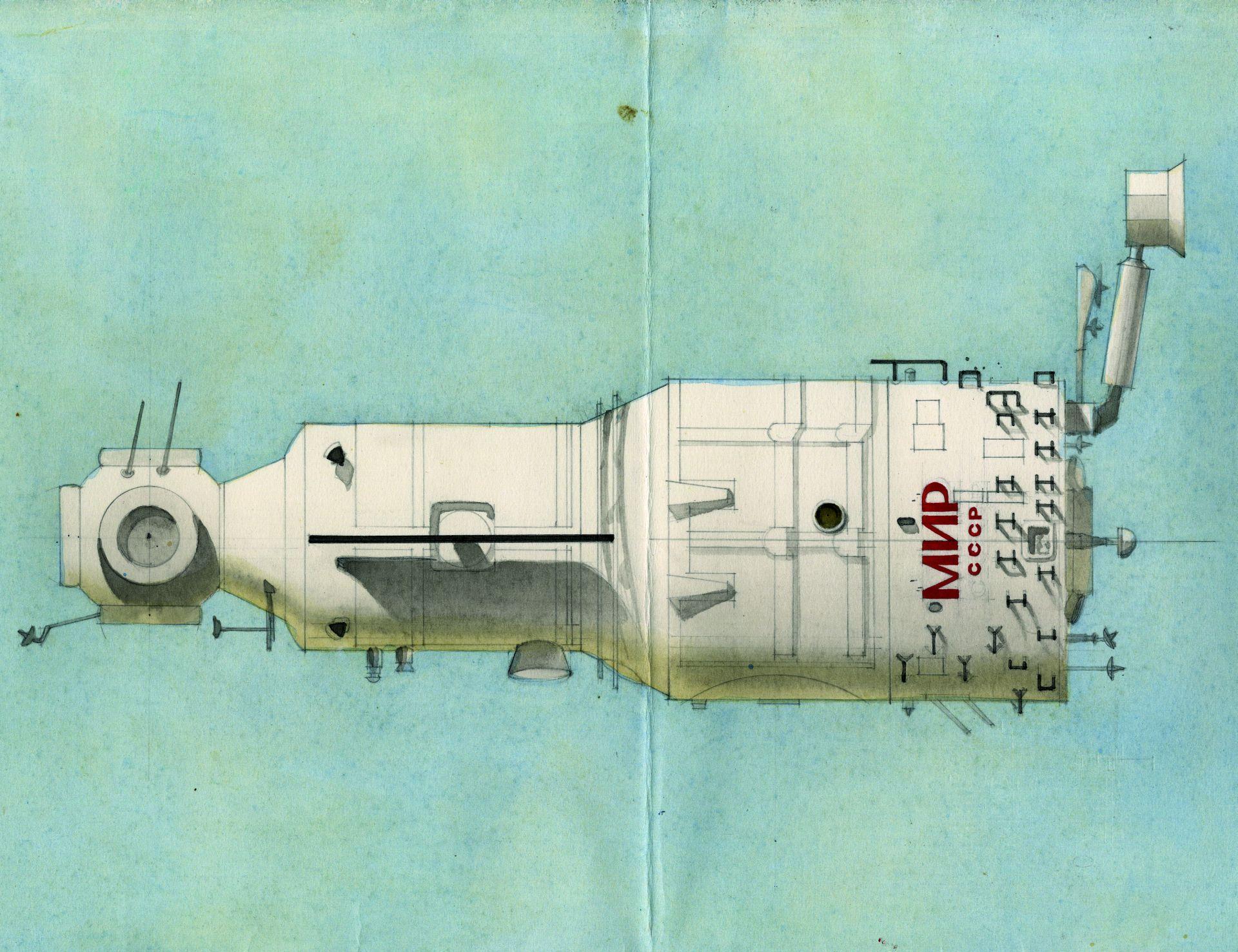

After decades of remaining classified under the Soviet government, the work of the space architect Galina Balashova has now been assembled by the German Architecture Museum (DAM) in Frankfurt- am-Main. Balashova had a hand in designing four generations of spacecraft: the plans for the Soyuz capsules, space stations Mir and Salyut, as well as the orbital glider Buran. The sole architect working amongst banks of aesthetically agnostic engineers, Balashova took on the utopian design challenge of making the void habitable. The marriage of experimental and meticulous thinking that Balashova brought to quotidian fixtures resonates with contemporary industrial designers such as Marc Newson. She conceived each minute de- tail: from logical button configurations on control decks, to chairs that accommodate weightlessness, to even the stitched insignias on cosmonaut outfits.

Hired by Sergei Korolev’s Experimental Design Bureau OKB-1 in 1957, Balashova operated behind the testosterone-charged posturing of Cold War propaganda. For over thirty years, hers was an anonymous form of political art that subverted the practices of her Russian constructivist forebears. Kazmir Malevich’s claims to autonomous zones of free-floating form seem pathetically abstract in comparison to Balashova’s designs. Within her architectural reality, objects and beings were truly free- floating, and she had the agency to tangibly shape the granular experience of space.

Balashova understood that to ensure the wellbeing of cosmonauts, capsule chambers had to mimic an environment where gravity exists. Her prototype de- signs of bookcases and foldaway tables evoke scenes from a typical modernist home of the time. Yet something more mysterious is at play. The design archetype of the terrestrial toilet bowl is informed by the earth’s ability to make things fall. However, under zero-gravity, such a design loses its functionality. Since Balashova’s constraints were dictated by laws of psychology rather than physics, these objects become hollowed-out surrogates for the domestic. Their cladding, fittings, and surfaces are uncanny shells floating within a distant yet strangely familiar environment.

It appears Balashova has straddled two perceptual realms since birth. Her first childhood memory was falling down a rabbit hole in the woods near her home in Lobna, a moment that she seems to revisit through her ouevre of watercolor landscapes. A prolific and skilled painter, she placed scenes of snowy Muscovite park- lands into light metal frames and attached them to the windows of Soyuz orbitals as a way of reminding the cosmonauts of life on earth. While the cosmonauts would return to earth in the landing module, these watercolors would either remain in orbit or be burnt up if they edged too close to the atmosphere – ephemeral odes impossibly longing for home. Floating amongst charred debris, they stand as artefacts of the iconoclastic soul within the Soviet cosmonautic machine, or perhaps just as silent missives to the gods from a suburban Sunday painter.