H.R. GIGER’s Private Life Was Just as Dark, Sexy, and Pop as His Art

The late Swiss artist H.R. Giger is best known for his xenomorphic monster in Ridley Scott’s Alien. Giger, who won an Academy Award for his design of the film, modeled the creature partly from Francis Bacon’s 1944 triptych Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion. It was composed in the studio using biological and mechanical materials such as snake vertebrae and Rolls-Royce tubes. The famous chestburster scene, in which the xenomorph is born, was filmed using freshly steamed offal from the local abattoir, including cow, sheep, and pig intestines plus a few parcels that defy categorization. “If the actor is just acting terrified,” Scott once said, “you can’t get the genuine look.” For his part Giger has said, “I never do harmless things like flowers. If they are flowers, they are the flowers that eat someone.”

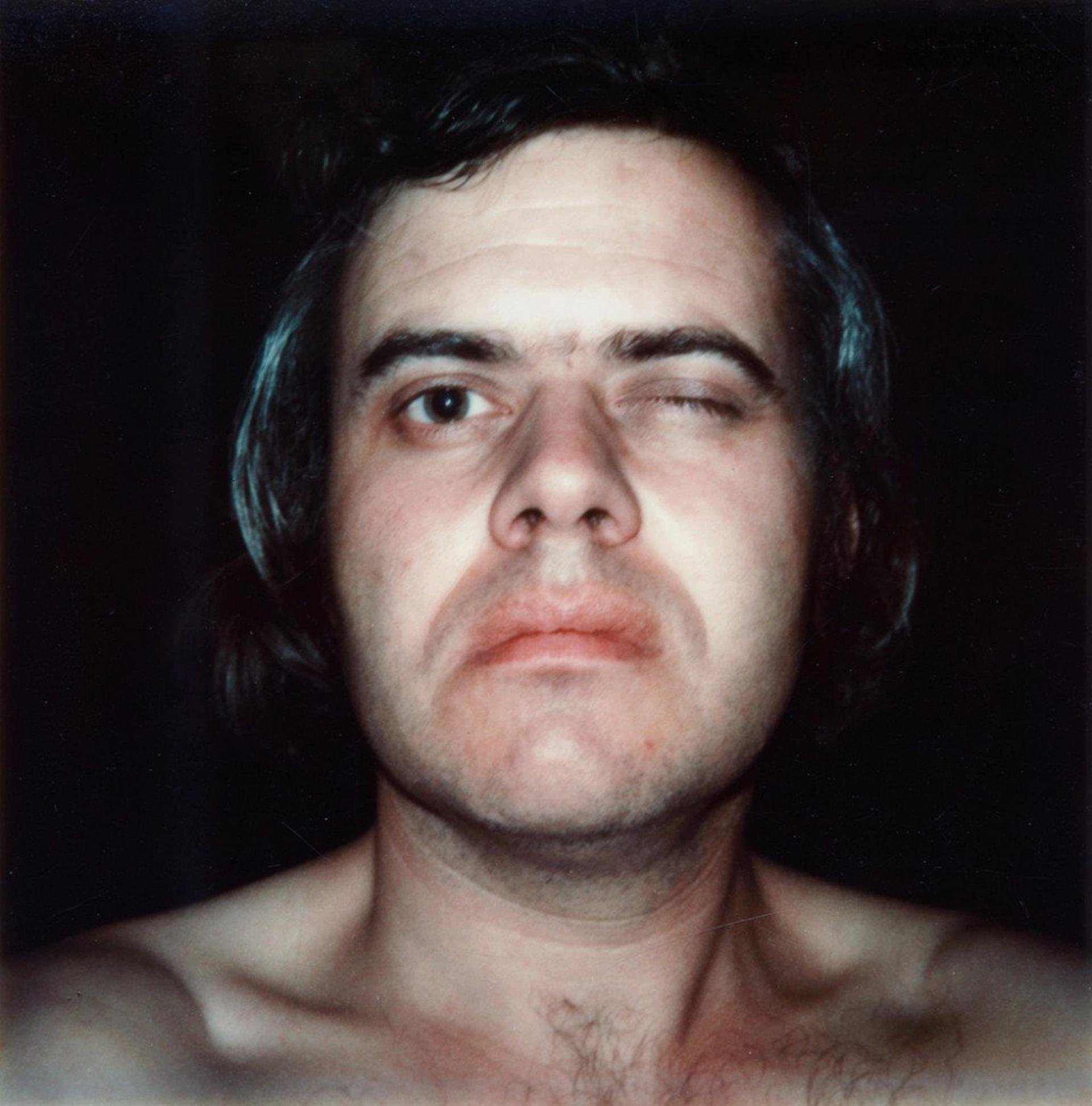

Yet Giger’s role in Alien did more than make the film scary—it also made it erotic. After all, sex, death, and biomechanics are what distinguish Giger’s true original oeuvre. In the recently published book H.R. Giger: Polaroids—comprised of a range of unpublished images by the artist—the skull model of the Alien head and tail are shown in 1979 series of two women using them as cyborg sex toys, BDSM beasts. Other Polaroids—which Giger personalized by scratching, painting, and drawing over them with surreal animations—include self-portraits, airbrushed fashion exoskeletons, and deeply disturbing moquettes that combine design, horror, fetish, pop, and an inscrutable sense of humor.

Over the course of 50 years, Giger, who was a friend to Alejandro Jodorowsky, Salvador Dalí, and Debbie Harry, created a grotesque gesamtkunstwerk that included paintings, scenographies, books, restaurants, and industrial design, and Polaroids presents a glimpse into the backend of this world, a kind of darkroom come to light. “Giger’s work,” claimed Timothy Leary, “shows us all too clearly where we come from and where we are going. It spooks us because of its enormous evolutionary time span.” Beyond its otherworldly form, Giger’s work was also a prescient aesthetic thrust into the post-Cold War politics that defined the last few decades of his life. “I was totally blown away the minute I saw it,” says Dead Kennedys frontman Jello Biafra about Giger’s work. “I thought, ‘Wow! That is the Reagan era on parade. Right there! That shows how Americans treat each other now.’ He captured it in a nutshell.”