House as Archive: James Baldwin’s Provençal Home

Somewhat removed from the fanfare of movie adaptations and much-promoted acquisitions of the past few years, Magdalena J. Zaborowska’s Me and My House: James Baldwin’s Last Decade in France appeared in April 2018. The book takes the Provençal home Baldwin occupied from 1971 to 1987, including the personal possessions that were subsequently salvaged from it, as “a lens through which to expand his biography and explore the politics and poetics of blackness, queerness, and domesticity” in the works he authored there. Drawing from interviews, letters, manuscripts, and personal experiences, the work is heavily illustrated, mostly with photographs taken by Zaborowska herself – no one else had endeavored to so thoroughly document the lived contents and grounds of Baldwin’s home.

Zaborowska, a professor of Afroamerican and American Studies at the University of Michigan, was struck by the intensity of her experience at the house, where the archival importance of the place itself and its material occupants became vivid to her. Me and My House richly describes Zaborowska’s time and interactions there, while calling for the preservation and elevation of the Baldwin material archive, and of others like it – the Black material archives ignored, forgotten or disregarded as a result of institutionalized value systems that prioritize the documents of white experience, to the brutal and systematic impairment of all others. Baldwin’s home is a place “no one will ever curate as a ‘writer’s house,’” Zaborowska writes, but we can use digital technologies to reanimate and repopulate the long-empty domicile such that others can share its experience. In the text below, Zaborowska narrates her early journeys to Baldwin’s home and proposes a salve for its recent loss: a virtual presentation of Baldwin’s home and effects, tentatively titled “Archiving James Baldwin’s House,” currently in the intermediate stages of archival research and digital production in collaboration with the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) in Washington, DC. Conceived between Baldwin’s place of origin and his chosen abode, and active at the borders of literature and architecture, material culture and its visual representations, the project seeks to make Baldwin’s things at home, anywhere.

The mantle above the fireplace in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, October 1987. Courtesy of the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC); photographer unknown.

Going to see Jimmy

I first heard of James Baldwin’s house in the South of France, which he called the “spread,” during a summer research trip in 2000. “Chez Baldwin,” as it was named by local residents, was just outside the city’s medieval stone walls, in one of the world’s most scenic locations – inland from Nice, overlooking the picturesque hills of Provence that slope dramatically to the bewitching waters of the Mediterranean. Instructed by a friendly bookstore owner in the postcard-pretty town of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, I found my way to the large, untamed property located along the sunbaked Route de la Colle, right outside the city’s ramparts and across from the famed hotel “Le Hameau,” where Baldwin stayed during his first visit to the area. I stood in front of a tall, locked black iron gate. A two-story garage-gatehouse with a steep external stair slashing against its wall stood to the left of the gate. It looked unkempt, overrun with hot pink flowering vines, but seemed occupied, as evidenced by a door left ajar and a red car parked on the street in front of the gate. At first glance, the property seemed a typical, crumbling Provençal structure consisting of several buildings, perhaps with proud origins in the 18th century. A large garden tightened its grip on the stone and tile of the main building, which stood at the end of a crumbling stone pathway.

I arrived at that locked gate 13 years after the writer’s death, dreaming of coming across something exciting and inspiring. Most of all, I hoped to see and absorb anything I could. Likely having noticed me peering into the property, a young woman appeared on the steps of the gatehouse. She was polite and friendly and accepted quickly that I, a holder of a small rectangle of paper, was indeed a professor from the University of Michigan who was researching James Baldwin in France. She gave me her mother’s phone number and told me to call her for permission to see the house. By a mere stroke of luck, the young woman’s mother, Jill Hutchinson, was available and let me see Chez Baldwin the next day, having explained that it remained largely in the state in which Baldwin’s younger brother David, who took care of the property after the writer’s death, left it in 1996. Removed against his wishes – he had wanted to remain with Jill and die in his brother’s house, in his bed – David was taken to the United States in the final stages of a terminal illness. Hutchinson had been his beloved partner, a terrific woman who had helped the Baldwin family for years by taking care of the house and its many repairs, renting it out to generate income for its upkeep, and handling many official and legal matters. She not only gave me, a perfect stranger, a day of her time to let me see the house, but later took me to her own place in the nearby town of Vence to show me Baldwin’s famed LP record collection that had traveled the world with him and the Legion of Honor medal given to him by the French president François Mitterrand in 1986. She had removed these items from Chez Baldwin after some burglary attempts convinced her that such valuable objects were not safe there.

“All of us know, whether or not we are able to admit it, that mirrors can only lie, that death by drowning is all that awaits one there. It is for this reason that love is so desperately sought and so cunningly avoided. Love takes off the masks that we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.”

Hutchinson assured me that over the years he had lived there, David Baldwin preserved the furnishings and layout of the house as much as possible in the way James Baldwin had left them at his death in 1987. She let me wander through the building, parts of which were unoccupied, and allowed me to take photographs. Although her friendship and later passionate relationship with David Baldwin did not begin until 1988, after Jimmy’s death – and she never met the writer – she had read his novels as a young woman in England and “absolutely fell in love with Another Country,” the book that “taught [her] how to really read.” Filled with rare antique finds and art, her house in Vence is a space of refuge, where some of the remnants of Chez Baldwin have found badly needed shelter. She told me fascinating stories about Baldwin’s residence and its inhabitants, passed onto her by David, who loved to talk about his brother and their life together as a family of men cohabitating in the house.

As we know from the biographies and documentaries, that family included Bernard Hassell, a beautiful dancer and choreographer who Baldwin met in 1952 at the Montana Bar in Paris during his first visit to France. Once James had moved into Chez Baldwin, Bernard came to live there and manage the household while taking the gatehouse as his quarters. He can be seen in photographs with Baldwin at the local inn and restaurant La Colombe d’Or; Beauford Delaney, a painter, created two portraits of him in the 1970s. Hassell’s relationship with Baldwin was never sexual, and they weathered many stormy times. One of their fights in the summer of 1974 ended up with Bernard being fired; he was brought back to re- store order in the increasingly chaotic household in 1976–77. He died at the house several years after Baldwin, a victim of HIV. Nicholas Delbanco offers an unforgettable vignette of Bernard arriving as part of Baldwin’s entourage to a dinner in the mid-1970s. They drove up in style, in Baldwin’s Mercedes, Delbanco recalls, “dark brown and substantial, just short of stretch-limousine size. … They were dressed for the occasion, grandly. They wore boaters and foulards. Their boots gleamed.”

Baldwin’s Christian Dior jacket in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Photo: Magdalena J. Zaborowska

Baldwin’s Led Zeppelin jacket in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. Photo: Magdalena J. Zaborowska

Friends, artists, academics, and celebrities passed through or stayed for a while at the house, as did lovers, most of whose identities have been protected in the biographies. Among the visitors were Baldwin’s close friend and possibly onetime lover Mary Painter; Cecil Brown; Henry Louis Gates Jr.; Josephine Baker; Nina Simone; Yves Montand and his wife, Simone Signoret; the writers Maya Angelou, Toni Morrison, Nicholas Delbanco, and Caryl Phillips; the actors, artists, and intellectuals Miles Davis, Eleanor Traylor, Louise Meriwether, and Florence Ladd; and many others. The Swiss painter Lucien Happersberger – who Baldwin met in Paris about 1950 and who inspired his second novel Giovanni’s Room – visited along with his wife and children (Baldwin was his son Luc’s godfather). Although their sexual love relationship did not survive beyond a few years, Happersberger remained an on-and-off close friend throughout Baldwin’s life; he took care of the writer’s ravaged body when he was ill with cancer, nursing him through the last weeks of his life.

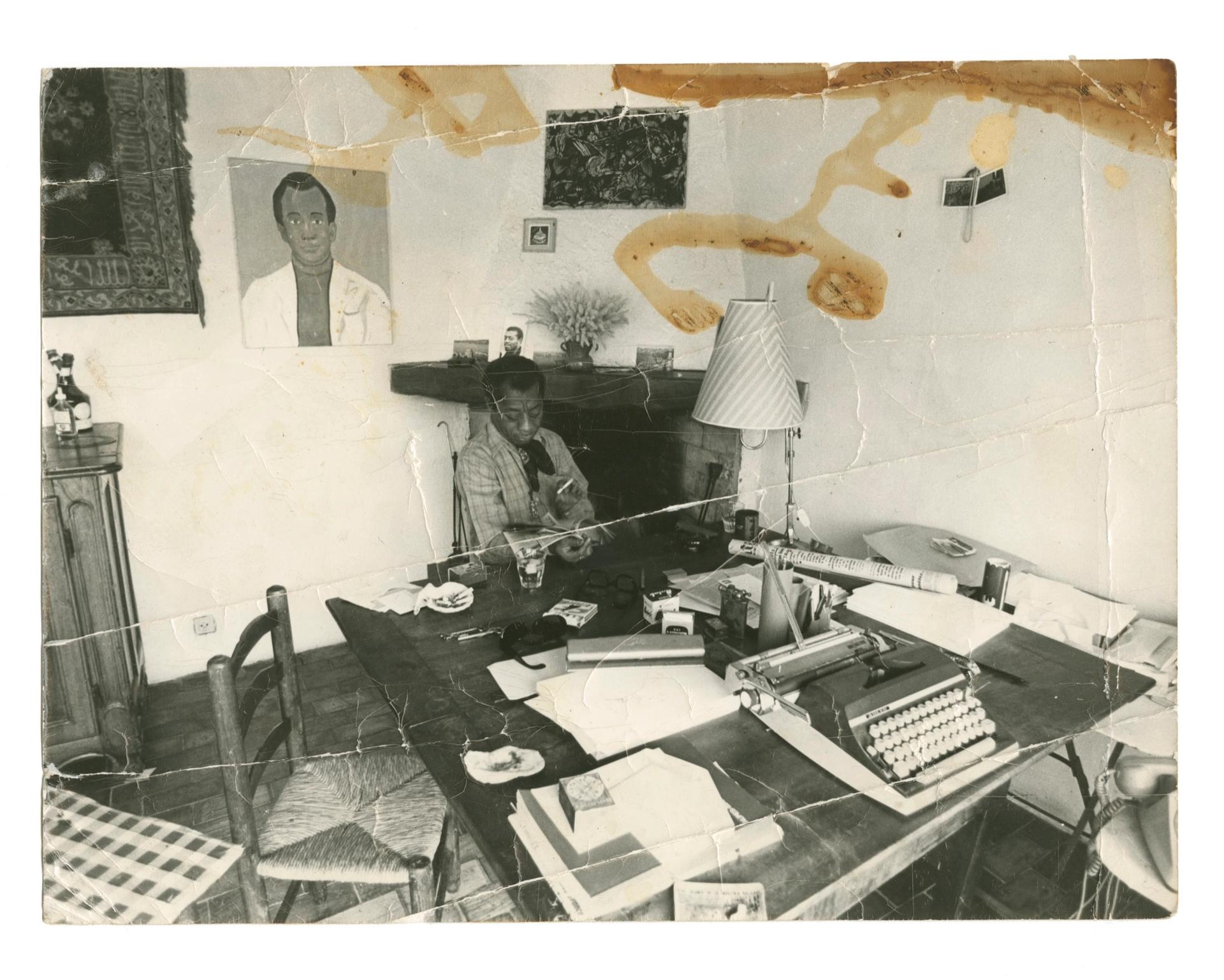

David Baldwin’s passing in 1996 halted his archival efforts to organize and secure the contents of the house, whose parts were subsequently rented out to provide income for its maintenance. While the manuscripts, diaries, and letters were removed by the estate following the writer’s death, everything else remained: a copious library, posters, paintings, photographs, files of Xeroxed material, two typewriters, furniture, knick-knacks, phone logs, and other ephemera. Jill Hutchinson, who was not allowed to accompany David on his final trip to the United States, was left alone to manage these complex matters while grieving her lover’s death and her inability to be at his side.

“You can’t sleep with a yacht,” Baldwin told anthropologist Margaret Mead in 1970. “You can’t make love to a Cadillac, though everyone appears to be trying to.”

My first visit at Chez Baldwin in June 2000, not even four years after David’s passing, involved a rather emotional tour of the house. Afterwards we sat, joined by my then partner Coleman A. Jordan, at James’ surviving welcome table under an arbor. That specific piece of outdoor furniture and another one in the living room were the actual objects that, besides an old hymn and Turkish parties with theater friends in the 1960s, inspired the writer to title his last play The Welcome Table (1987). While in the lush garden, we wore Jimmy’s “guest” straw sun hats, which Jill picked up from the hooks by the side door leading to the kitchen; she explained that they were necessary in the Provençal climate, and that we ought to wear them to honor Jimmy. Bathed in dappled sunlight, surrounded by the breathtaking views of the area, with the ancient crumbling house looming behind, we may have made a picture worthy of an impressionistic painting.

Inside the quiet house, the walls were generously decorated with David’s artwork and photos of Baldwin and his friends and family, posters, and, in some of the upstairs rooms, peeling frescoes that may have been a century old or older. Bookshelves overflowed with volumes. David may have contributed books and records to the sizable collections that were left at the house. After James’ death, he answered many letters from individuals and institutions hoping to obtain permissions to stage the writer’s plays, look at his papers, publish news releases, or quote from his works. Though uninhabited for some time, the interior, filled with furniture and objects, seemed eerily full of life, as if vacated seconds ago. It seemed to be awaiting the return of the brothers, who had stepped outside for just a moment.

“Perhaps home is not a place but simply an irrevocable condition.”

James Baldwin – Giovanni's Room

I lingered in front of the study on the ground floor at the back of the house (I could not look inside as it was rented out at the time), where Georges Braque had once had his atelier, and where Baldwin had his writing study, or “dungeon” and “torture chamber,” as he called it in a letter to David dated March 8, 1975. This letter, full of details about the writer’s daily labors, talks about him “sweating out his volume on popular cinema,” The Devil Finds Work; it describes him being “scared shitless” about finishing it, and him being “about to turn it in.” The letter reveals what we rarely saw in his public appearances: an insecure and terror-stricken writer who muses about having to discover, when the “book The Devil is almost over,” that he is, in his own eyes, the “world’s worst” author and has “no talent at all.” He frets, in a diva mode, that he cannot imagine “anybody ever” reading his book, but is certain that at this crisis point, “either it, or I,” will be forced to “leave this house.” These thoughts on authorship reveal someone never fully secure in his talent, who approached every writing task as a terrifying challenge and every completed project as an occasion for crippling self-doubt. The section of the letter devoted to Devil ends with an affirmation, however, that acknowledges that even though the book is not “like anything” he has done before and “I just don’t know,” his lover, “Philippe,” thinks it “very good.” The book was composed inside a study that consisted of the workroom and the writer’s living quarters, equipped with a small kitchen and a bathroom. Baldwin liked to take breaks to read or edit on the patio, sitting at a round wooden table in front of it.

The teeming garden, which embraced the house on all sides, was filled with places to sit and take breaks; it also held Baldwin’s welcome table, which appears, with the writer sitting at it all alone, in his Architectural Digest piece. A pathway leading to the side of the property, and festooned with dense greenery, was still adorned with strings of colorful light bulbs hanging over a metal frame that supported the vines – a remnant from Baldwin’s 50th birthday party on August 2, 1974, “an occasion long talked about. … More lights than ever were strung in the little orange grove, the food and wine ‘never stopped.’” I walked through the now overgrown, densely green tunnel and could easily imagine it all lit up at night, framing the many guests’ laughter, conversation, and jokes drifting around with cigarette smoke.

On a wall by an arched passageway that led to the back of the property on the left side of the front of the house, a small, immured mirror blinked. Jill told me that Jimmy, always a sharp dresser and meticulous about appearing “impeccable,” would check his looks in it before joining his visitors in the garden. As I wandered around, the never-realized plans, Baldwin’s deathbed wish to transform the property into a retreat for African Diaspora writers, made a lot of sense. Despite the many loud parties, arguments, and fights it once witnessed, the peaceful and nurturing energy of the house and its surroundings was palpable, and the main building and adjoining structures were spacious enough to accommodate at least a dozen guests in separate studio bedrooms.

James Baldwin’s belongings in storage in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 2014. Photo: Magdalena J. Zaborowska

The attention that readers and scholars pay to places where important works have been created, and to structures, cities, and landscapes that inspired memorable lines of texts, stems from the need to anchor the material and make tangible what is elusive and impermanent about literature, and from our hope to share in imagination and inspiration. The need to see the places where writing happened emerges from the desire for closeness to one’s subject. What better place to feel inspired than within the walls that once housed the admired writer?

When I returned to Saint-Paul-de-Vence in 2014, the house was empty and run down. I was also fortunate to survey what remained of Baldwin’s authorial haven – books, journals, magazines, files of photocopied pages, vinyl records, photos, posters, framed artworks, an electric typewriter, and print clippings that used to spill over shelves and desktops throughout the house. I came back to finalize the documentation of that archive in 2017 and then, in 2018, to document new objects from the collections of the sisters Pitou Roux and Hélène Roux Jeandheur, whose mother Yvonne was Baldwin’s closest friend in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. The 2014 visit, on which I took many photographs of the house, took place just months before a demolition erased the wing that housed Baldwin’s study and living quarters. By now, the house’s surviving tallest central part has been lost to a hideous development project.

The piles of boxes constituting the material remnants of Baldwin’s life have survived to this day, painstakingly moved from one storage location to the next because of efforts colored by deeply personal motivations. For Hutchinson, this meant salvaging and preserving the objects that filled the house and that David Baldwin had kept in memory of his beloved brother. As she told me, fully aware that he would not see her again, David begged her to “take care of the house.” She removed the most personal pieces to her own house, and packed up others and placed them in storage. For me, the storage boxes I encountered in 2014 seemed filled with treasures that could reveal Baldwin’s reading tastes, the musical soundtrack of his everyday life, the names and numbers of people who called and left messages noted on loose pages of a telephone log, and many files of material he used to research his works, like those for his little-read brilliant last essay volume, The Evidence of Things Not Seen (1985). Unlike the artifacts precious to traditional archives and libraries – manuscripts and letters that the Baldwin estate has recently sold to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture – the contents of his bookshelves, an electric typewriter, old photographs, and artwork were abandoned as possessing no value, as “not unique,” as an archivist once explained to me – to her they were detritus: refuse, if not trash.

“I am a writer. I like doing things alone.”

There are now two small historical markers honoring Baldwin in New York City’s Harlem and Greenwich Village neighborhoods: a street sign proclaiming “James Baldwin Place” on 128th Street, between 5th and Madison in Harlem, where the building of the former P.S. 24 grammar school, which Baldwin attended, still stands, and a plaque on the house on Horatio Street that he occupied for a while in the late 1950s. Yet in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, there is not even a sign with his name and information confirming his residence. This absence – not at all surprising given how few African American writers’ houses are open to the public in the United States – only compounds Baldwin’s “homelessness” as one of the most important African Diaspora writers and intellectuals. Much like those of countless other black Americans whom the new NMAAHC in Washington honors, his legacy remains in flux, the material traces of his life almost completely erased in this country.

The need for a virtual house museum for Baldwin may not seem urgent or obvious to those who consider his published works the only terrain worth examining and his manuscripts the only material part of his life worth salvaging. Scholarly desires for material preservation are more often than not at odds with those of estates, lawyers, and kin, not to mention archives and libraries. While the leftover Chez Baldwin artifacts I have studied were abandoned, I read these items as central to and marking Baldwin’s daily life as a writer. These objects demand reading as rich evidence of his black queer dwelling practices that were key to the composition of his important late novels and essays, works that are finally being recognized for their daring form and message, like If Beale Street Could Talk, The Devil Finds Work, Just Above My Head, The Evidence of Things Not Seen, and especially his unpublished play The Welcome Table.

Foreign language editions including Baldwin’s "If Beale Street Could Talk", "The Devil Finds Work", and "Giovanni’s Room". Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 2014. Photo: Magdalena J. Zaborowska.

While offering rich visual documentation of the very milieu that enabled the writing of these works, a virtual Chez Baldwin house museum would resist the material erasure of Baldwin’s life in the United States and France, and elucidate the unequal valuation of Black and white literary legacies. For scholars, teachers, and readers everywhere, we must make good use of Baldwin’s contribution to writing and rewriting the conundrums of Black domesticity, whose full impact on the US national house, which in a 1980 article for The Nation he termed the “house of bondage,” we have yet to acknowledge. In this house, Black people are not made to feel at home; even national heroes remain homeless here, like Rosa Parks, whose Detroit house was recently slated for demolition. After Parks’ niece Rhea MacCauley had exhausted appeals to local authorities, she purchased the structure for 500 dollars and caught the attention of an American artist living in Germany, Ryan Mendoza. He painstakingly took the house apart and paid for its transport to Berlin, where it became a museum. Why did this house have to be taken across the Atlantic to be saved? Why did the largest Black city in the nation not have sufficient interest and resources to save it?

What we understand as the matter of Black lives, its materiality, traces, remnants, and even refuse, has always been read differently from the matter of white lives, which have so far taken historical precedence in the museums populating the US national house. How is it, one may ask, that Baldwin’s house library has been abandoned as worthless, while the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University cherishes Walt Whitman’s reading glasses as a precious artifact? While visiting to give a talk there, I asked two archivists from the Beinecke to discuss the remaining archive of books, objects, clippings, artwork, and photographs from Chez Baldwin, and the possibility of their acquiring it. To my astonishment, the archivists explained that, unless there were provable traces of Baldwin’s “hand” on the books and other materials, they did not see any value in preserving these objects because they were not “unique.” The problem was an insurmountable difference in vision and imagination, and certainly in experience: I saw the books, files, magazines, and clippings as possessing great, unprecedented value in the simple fact that they once belonged to Baldwin, while the archivists, however they were trained, saw no value whatsoever in these materials.

Most glaringly, they neither comprehended the racial underpinnings of the cruel paradox, nor saw the point of answering the loaded question about Whitman’s reading glasses versus Baldwin’s library, photos, artwork, vinyl records, and an old, spare electric typewriter. A few months ago, as if in response to my scholarly rage concerning that response, The New York Times reported that the Beinecke had recently bought Jonathan Lethem’s entire archive, including “dead-tree artifacts.” The very same person who saw Baldwin’s possessions as worthless spoke of this part of Lethem’s archive as “playful” and “charmingly weird,” and boasted that the purchase included his comic books, a trove of electronics, and many a drunken drawing of “vomiting cats” by the writer’s friends.

“True rebels, after all, are as rare as true lovers.”

This issue of appraising what constitutes a writer’s archive and material legacy, so obvious to some, is invisible or even incomprehensible to others. I see it as directly linked to what Saidiya Hartman terms the “violence of the archive,” or the impossibility and scarcity of material documentation of Black lives, the “archival silences,” if not the deliberate erasure that those who work in African Diaspora studies have to contend with, no matter their historical focus. Today, we take for granted that electronic devices have become our “environments” and that we “inhabit” them. Hence Lethem’s tablets, iPods, and laptops seem valuable sources of information as “born-digital archival holdings.”

The archive is not only personal and political: it is also filled with emotions, projections, and memories – it is a playground for interpretation, and who experiences it, and how, matters. Especially needed in African American studies, where documentation, interpretation, and preservation efforts have been historically hampered by racialized systems of adjudicating research results and archival values, are digital tools that can help us to fight back, but that also require that we use them wisely. In its desire to preserve, to the degree that a project like this allows, what remains of the matter and stories of the domestic life of James Baldwin, “Archiving James Baldwin’s House” offers an assembled portrait of a writer whose imagination and passion for social justice filtered through all kinds of intellectual and visionary spaces – from nation to city streets to the privacy of the bedroom. By contextualizing Baldwin’s ideas within his biography, scholarship, and recent popular events devoted to his legacy, as much as within his complex literary works, his house, and the eclectic archive of material objects salvaged from his dwelling, this virtual writer’s museum will highlight his personal contradictions, challenges, and struggles, which his essays, interviews, and brilliant letters reveal as being always unabashedly political, regardless of current theoretical vogue or idiom. Baldwin’s proud domestication of our shared humanity and his fierce embrace of himself as a marginalized subject and inimitable individual – “black, poor, and homosexual,” as an interviewer once put it – constitute his most enduring gift.

In the redevelopment plans, the entrance to an underground garage occupies the former site of Baldwin’s “welcome table,” where the author wined and dined his wide circle of 20th century luminaries. Saint-Paul-de-Vence, 2017. Photo: Magdalena J. Zaborowska.