Origin of the Gothic and Sublime: Becoming RICCARDO TISCI

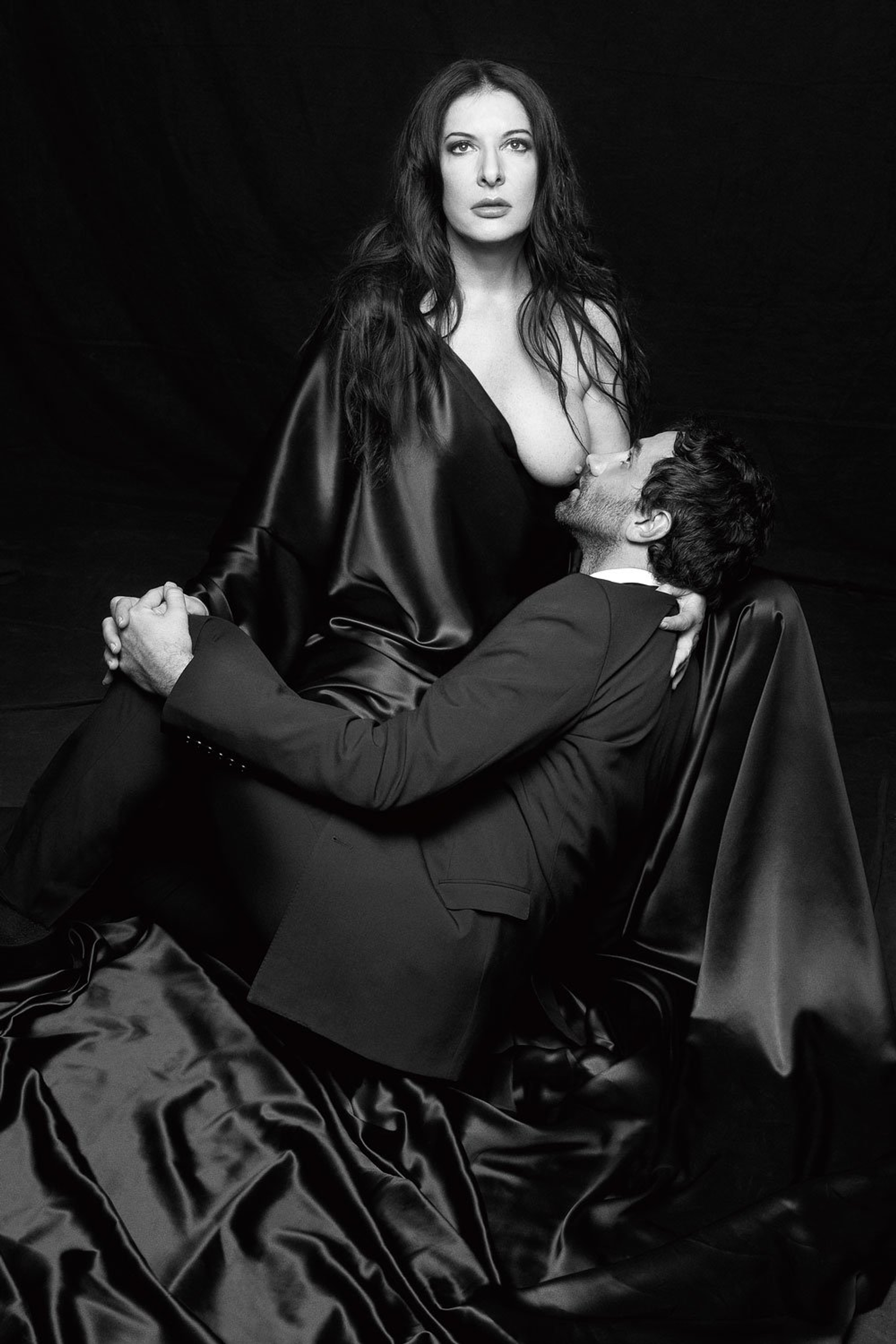

Photo: STEVEN KLEIN, Interview Magazine, 2011

Riccardo Tisci, Burberry’s chief creative officer since 2018, has been called “gothic” in the press since 2004.

“Gothic” is an elastic descriptor, one applied by critics more than by creators across cultural disciplines. Giorgio Vasari used it as an insult in Lives of the Artists (1550), describing the ornate architecture of a medieval cathedral. The art historian deemed the structure – with its rounded arches, rose windows, and gargoyles – offensive and barbaric, inferior to the classical style favored by his Renaissance contemporaries.

Vasari used somewhat literally the term “gothic,” which derived from the Ostrogoths and Visigoths – nomadic warriors who “polluted the world” with their “deformed structures,” bringing the gilded age of the Roman Empire to an end and plunging civilization into the Dark Ages.

“In every hard story, you find romance,” Tisci has said of Thomas Burberry, the self-made Victorian visionary who founded the British house at age 21. A fellow self-made man, Tisci also started from humble beginnings. The designer grew up in a Roman Catholic household near Como, a lakeside town that is home to Italy’s so-called last gothic cathedral. Tisci was one of nine children, reared by a widowed mother from Puglia who could “feed an entire family from one piece of bread.”

Album cover: Jay-Z and Kanye West, Watch the Throne, 2011 Artistic direction: Riccardo Tisci

He traces his fascination with beauty and fashion back to a childhood spent watching, in delight, as his eight sisters teased their perms and applied blue eyeshadow, a process he called a “ritual” of transformation. Tisci has described the women in his life as “warriors” who would come home every day and remove their armor, transforming back into nurturing caregivers. He was shy as a teenager and, coming of age in the heyday of new wave, shielded himself in dark armor of his own design: capes and platform shoes to complement his long black hair and pale makeup.

Tisci’s appointment at Burberry was a kind of creative homecoming. He first left Italy for London at 17, embarking on a chivalric quest for economic opportunity in support of his family. England delivered: his exceptional illustration skills earned him a full scholarship to Central Saint Martins. Like any good fashion student, he ended long days in the studio with nights out on the town. In the spirit of the New Romantics – who made London nightlife sparkle again, after the somber years of punk – Tisci blossomed after dark, refining his aesthetic on the dance floors of the 1990s. England, Tisci says, is where he learned to be himself.

His graduate presentation landed him jobs at Puma and Ruffo Research, where he worked before launching his own label in 2004. He showcased his second collection off season, on the outskirts of Milan. There, his model and muse, Mariacarla Boscono, emerged from a cloud of church incense; she wore a long, vampiric coat and strode onto a catwalk with a crucifix and funeral pyre as her backdrop. Days later, Tisci received a call from CEO Marco Gobbetti: he was summoned. Soon, a castle-dwelling aristocrat by the name of Hubert de Givenchy would hire Tisci to help revive the storied maison.

“For two months, I was wandering around my house like a ghost,” Tisci has said of the improbable mission. He was just 30 years old when he arrived in Paris, shod in worn sneakers, and introduced himself to skeptical atelier staff. “They were a bit afraid of me in the beginning,” he has recalled – and, in retrospect, they had reason to be. Tisci was about to transform a traditional couture house into a test site for experimentation. In doing so, he became one of the fashion industry’s most lovable heretics.

Photo: DUSAN RELJIN, Visionaire Magazine, 2011

"They called me the antichrist,” Tisci has said. New York Times’ fashion critic Cathy Horyn called him fashion’s "latest cabbage patch discovery”; Vogue’s Sarah Mower summed up his “first stab at ready-to-wear” in one word: “painful.”

The critique cuts to the heart of Tisci’s aesthetic aims, which he continues to develop at Burberry to this day: to move beyond fashion’s preference for the beautiful and, instead, use clothing to attain the sublime. Beauty is the domain of classicists, of those seeking good taste, but the romantic seeks powerful and awesome sublimity. In the writings of philosopher Edmund Burke, “pain” – as passion or as fear, in death and eroticism – is precisely what distinguishes the two.

Tisci is credited with kickstarting luxury fashion’s streetwear craze. He put a snarling rottweiler – his own gargoyle – on a t-shirt, and Swarovski crystal skeletons on catsuits in a collection seeking “a romantic way to see death.” In athleisure, he printed “PERVERT” on jerseys and put Bambi, cut in half, on sweatshirts. He cast models as gothic temples, painted their faces like stained glass windows, ornamented their architecture with oversized septum rings and gilded crowns of thorns.

As millennials joined the cult of social media, Tisci became an ordained priest of viral fashion. He sent Beyoncé to the Met Gala in a latex ballgown, Madonna in a breastless bodice and chaps veiled in lace. As the stylist for Kanye West’s Watch the Throne tour, he put the “Devil in a New Dress” rapper in a leather kilt. He cast transgender model Lea T as the face of his AW-10 campaign, and Kim Kardashian as the Audrey Hepburn of the 2010s, working the miracle of her transformation from reality TV star into style icon.

Photo: AGATHE POUPENEY, BÓLERO, 2013. Costume design: RICCARDO TISCI

Tisci recruited his “artistic soulmate,” Marina Abramović, to help him take on the ultimate taboo: a seasonal presentation-cum-performance piece commemorating 9-11 during New York Fashion Week. Vanessa Friedman wrote in The New York Times that Tisci’s show demonstrated, “as gracefully as [she had] ever witnessed, the power of fashion to reflect history and experience; to weave it, literally, into the garments we wear.”

By the end of Tisci’s “50 Shades of Black”-themed tenure at Givenchy, staff tripled, sales reached 500 million euros, and Tim Blanks christened him as “fashion’s dark night of the Catholic-Gothic soul.” His personal signatures – his emphasis on representation, his high esteem for streetwear, his use of the digital feed as a never-ending catwalk – became luxury fashion protocol. “Basically anything you like, or don’t like, about fashion in the past ten years,” Kanye said in 2019, “it’s Riccardo’s fault!”

Three years ago, Tisci broke away from the authority of Europe’s fashion conglomerates, like Henry VIII leaving the Catholic Church – the original house of luxury. He returned to his professional birthplace to take the supreme creative helm at Burberry, a heritage brand synonymous with Britain itself and entrenched in outerwear iconolatry.

Established in London in 1856, the house of Burberry came with its own holy trinity: the insignia of the Equestrian Knight, who carries a flag emblazoned with “Prorsum” (“onward,” in Latin); the Burberry Check, a tartan pattern so sacred and subversive that it sparked a Reformation; and the trench coat, a gabardine institution in foggy Westminster.

Tisci arrived at Burberry with a spirit of iconoclasm and with “Prorsum” as his rallying cry. He tapped Peter Saville for a graphic revision of the brand’s insignia, and with the Unknown Pleasures album designer, Tisci replaced the heraldic trinity with a logo containing only three essential terms: Burberry, London, England.

Photo: JUERGEN TELLER, BURBERRY/SS-21

Photo: DAVIT GIORGADZE, BURBERRY/AW-20/21

Photo: COURTESY OF BURBERRY, 2020

Photo: BIBI BORTHWICK, BURBERRY/SS-21

Aimed at shedding preconceptions associated with these proper nouns, and ones linked to the designer’s own name, Tisci’s debut season was, at once, a love letter to Burberry’s roots and a call to reinvention. He named the collection “Kingdom” – but sought to carve out an inclusive domain in which monarchs coexist with football hooligans and London punks, and where the separatist nation’s ingrained social hierarchy is flattened and replaced with an expanded and more pliable view of Britishness. Signaling a future of fluidity, Saville created a new grid of Ts and Bs – for founder Thomas Burberry, and perhaps for Tisci’s Burberry, too – to integrate the label’s contradictions on fabric prints.

Photo: DANKO STEINER, BURBERRY/SS-19

Photo: JUERGEN TELLER, BURBERRY/SS-21

Photo: NADINE FRACZKOWSKI, BURBERRY/SS-21

Photo: RAFAEL PAVAROTTI, BURBERRY/2020

At Burberry – a brand born of a desire to better coexist with the environment, to be in the streets of rainy London or on the icebergs of Antarctica – the Tiscian sublime looks different. Like the well-dressed subject in Caspar David Friedrich’s painting The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1818), Tisci confronts the natural world from his human, designed, urban one. Since arriving at Burberry, he has staged fashion shows in the forest, adorned models with prosthetic fawn ears, and taken artist Anne Imhof out of her punk element and into the wilderness.

“People say I’m gothic,” Tisci once told a reporter, “but I think of it as being in love.” Emotion is the foundation of the designer’s work, and the purity of feeling – of longing, of fervor – that informs his practice feels transgressive at Burberry, a product of a culture known for its reserve. Yet perhaps of all the archetypes from the romantic tradition, it is the brooding English protagonist – the Byronic hero – who is closest to the darkness of his own yearning, and whose unbridled passions and desires are heroic precisely because they defy the codes of social conditioning. The presence of this friction – between restraint and passion, the pastoral and the glamorous, the picturesque and the sublime – means Tisci at Burberry is Tisci at his most radical.