Human Animal Demon Machine: LEE BUL’s Crash at the Gropius Bau in Berlin

Just hours before a recent exhibition by the South Korean artist Lee Bul was scheduled to open at the Hayward Gallery in London, a rotten fish caught fire. More accurately, a series of rotten fish caught fire. The carcasses, covered in shiny beads and suspended in gas-filled Mylar bags, were part of Majestic Splendor, an installation originally created for Lee’s 1997 show at the Museum of Modern Art New York, to which potassium permanganate had been added to address visitors’ complaints about the work’s smell. (Though not flammable itself, the gas changes the properties of the objects it comes into contact with.) The damage from the Hayward fire was minimal, but the incident speaks revealingly about the unique material agility of Lee’s creations, in which the inorganic, the living, and the decayed fuse to create overwhelming impressions of beauty and terror. Experiencing them is a bit like watching something burn.

Born in 1964, Lee will open her first solo exhibition in Germany this Saturday, September 29, at the Martin-Gropius-Bau in Berlin. Raised under the autocratic premiership of Park Chung-hee, Lee strove to forge a new idea of femininity early on in her career, through participatory works formed in response to an environment where women’s bodies were strictly policed and abortion was (and still is) illegal.

At times she would appear wearing bulky costumes, delicate yet grotesque, resembling bodies turned inside out – a combination of insect, flower, and machine that the sculpture and installation artist refers to as “anagrammatical morphologies.” At the Gropius Bau, these suits are suspended amid newer works, dreamscapes, and architectural interventions that draw influence from speculative fiction, critical theory, and cinematic dystopias. A general sense of longing – for perfection, perhaps for transcendence – is met by a feeling of immanent dread in this work, recalling such artists as Caspar David Friedrich for his awe-filled romanticism, Italian Futurist Piranesi for his mechanistic labyrinths, and Bruno Taut for his “alpine architecture.”

Exhibition curator and newly minted Gropius Bau director Stephanie Rosenthal spoke to 032c in advance of the opening of Lee Bul: Crash, as Berlin gears up for its fall Art Week.

The artist Lee Bul. Photo: Kim Jae Won, courtesy of Studio Lee Bul

How did such a large solo show come to take place? Why now?

I am very familiar with Lee Bul and her work, having followed her practice for many years, and I was able to engage with her closely after inviting her to be part of the Biennale of Sydney in 2016. Following this, it became apparent to me that despite Lee Bul’s work being known around the world, she had not had a large retrospective in Germany and I felt it was the right time for this to happen.

The exhibition is a mid-career survey that showcases several of Lee Bul’s important works from the beginning to 2018. Lee Bul: Crash is also the perfect first show for the programmatic vision of the Gropius Bau. She is a woman who creates mesmerizing and at the same time deep and meaningful work. Her pieces resonate with their surroundings, reflecting the location and the space of the Gropius Bau, which will continue to be an important aspect for our program for the next three years.

How does the political manifest in Lee’s work, and has the work changed as South Korea transitioned from dictatorship to democracy?

Lee Bul was raised during a strict military regime in South Korea, which shaped many of the concepts we see in her oeuvre. Her works look both outwards and inwards, subtly alluding to Korea’s history and political environment. Her decision to use her work to voice oppression, pain, and vulnerability in this sense is deeply personal.

One work that is closely linked to this time is Thaw (Takaki Masao) (2007), which refers to Park Chung-hee, who established a military dictatorship in South Korea in 1963, and who had adopted the Japanese name “Takaki Masao” while training in the Manchukuo Imperial Army. Park served as President during the 1960s and 1970s – while Lee was a student – before being assassinated in 1979. When Park first came to power he set about creating a socialist state in South Korea. However, this idealistic future mutated into a repressive, autocratic reality.

Lee Bul, "Untitled (Cravings Red)", 2011 (reconstruction of 1988 work). Photo: Jeon Byung-cheol, Courtesy of Studio Lee Bul

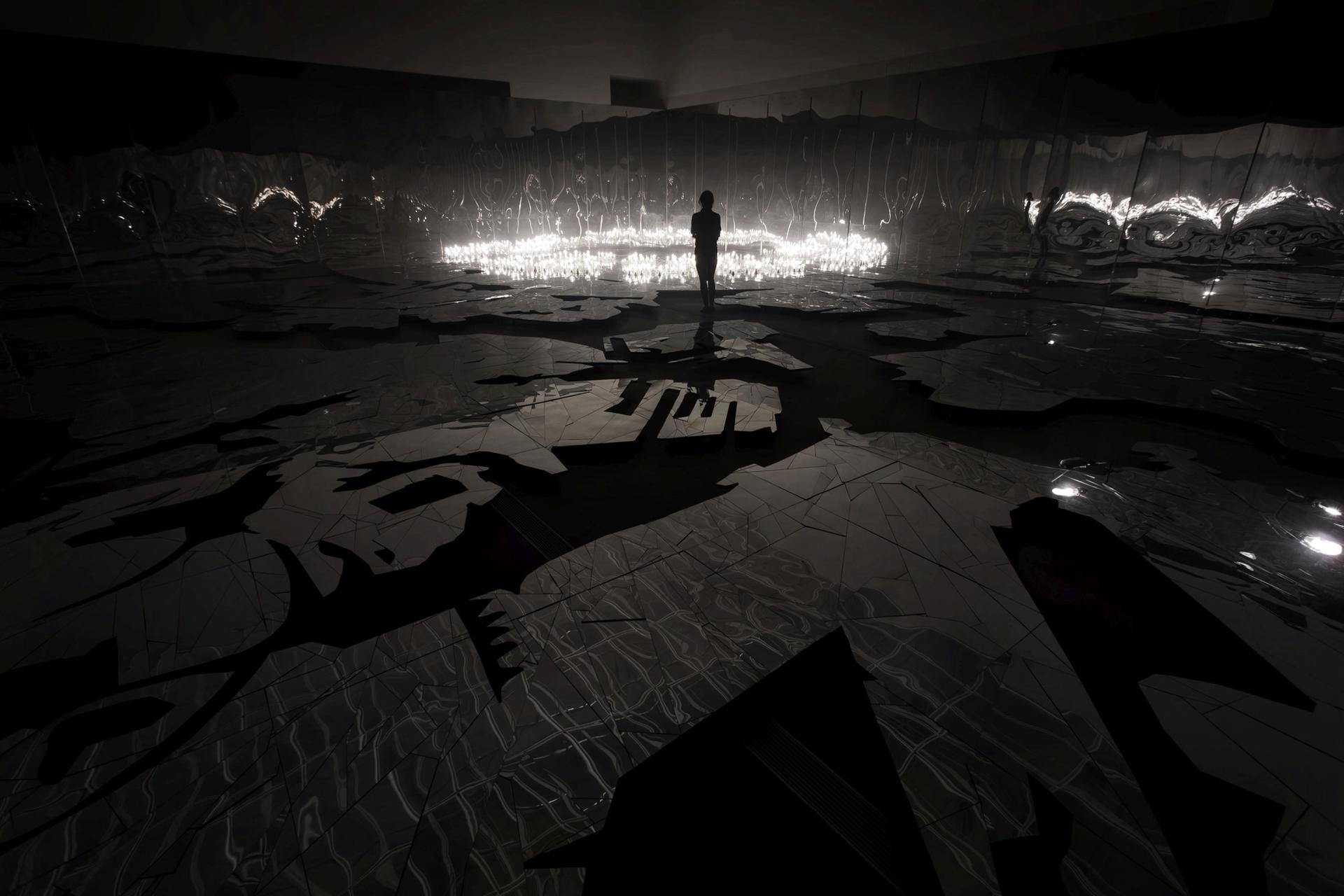

Lee Bul, "Via Negativa II", 2014. Photo: Elisabeth Bernstein, courtesy of Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong

What is unique about Lee’s choice and use of materials?

Lee Bul’s choice of materials is unusual and deeply thought provoking, some alluding to textures of the body, others recalling moments from her childhood environment, such as her use of beads, mother-of-pearl, crystals, leather or velvet. Lee Bul also frequently uses mirrors and mirrored materials – especially for her immersive installations. She appreciates the material for its disorientating and destabilizing qualities, and its ability to bring our bodies – and the bodies of those around us – directly into the works, which are capable of transporting the audience to a different reality, a different place, and a different time. As she explains herself, “I choose what I work with carefully. Everything has connotations, stories.”

These surfaces, when placed alongside each other, align with the concept of the works, creating a tension through their juxtaposition and illustrating conflicting connotations and the layers of meaning Lee sees in utopian idealism.

How does Crash differ from Crashing, Lee’s recent exhibition at London’s Hayward Gallery? And what might the historic location of the Gropius Bau offer Lee’s preferred themes?

For both Crashing at the Hayward Gallery and Crash at the Gropius Bau, the curation responds directly to the location and the audience, offering an alternative perspective on Lee Bul’s oeuvre. The way we have chosen to present her work here in Berlin is very different. While in London the works were shown in five large spaces alluding to the connection between works from different times, in Berlin we focus on the individual works and show them spread over 20 rooms, very often in spaces with large windows that remind visitors of the location of the Gropius Bau.

With the construction in the post-war era of the Berlin Wall directly alongside the north façade of the building, the Gropius Bau was situated close to the border and consequently in the middle of political conflict. This history in many ways draws a parallel to the unsettling alienation and trauma experienced by Lee Bul as a result of Korea’s division and period of dictatorship. This time has greatly impacted her work and is demonstrated through her personal portrayal of architectural topographies and visions of a tainted utopia.

Crash highlights the historical and the political, demonstrating the international relevance of Lee Bul’s work by connecting themes seen in both German and Korean history, with a special focus on these countries’ histories of division, the national trauma related to this division, and the question of reunification.

Lee Bul, "Cyborg W1", 1998. Photo: Remi Villaggi, courtesy of Studio Lee Bul

Lee Bul, “Willing To Be Vulnerable”, 2015–2016. Photo: Algirdas Bakas, courtesy of Studio Lee Bul

Both titles allude, intentionally or not, to J. G. Ballard – a key influence for Lee. How do you understand the connection between the novelist and artist?

Lee Bul has been interested in J. G. Ballard since the late 1990s. Her interest is not only in the way Ballard uses landscape as an expression of an internal emotional state, but also in the way he uses language. Crash was a fitting title for us also because Lee Bul’s approach is about “crashing” together material and content that are seemingly opposed to each other. Beauty and horror, or pain and joy, lie very close together in her work.

There is a sense of existential danger, of longing for technological and architectural utopias, in sculptures such as Willing To Be Vulnerable (2015-2016). Is this a more recent turn in Lee’s oeuvre?

I wouldn’t describe it as a turn. Lee Bul’s investigation into the failings of utopian realism are rooted in her earlier works, notably in her series Cyborg (1997– 2011), which are on display in a light-flooded corner room of the Gropius Bau. Lee Bul is interested in the way humans are constantly striving for perfection, and in how we are always failing to achieve it, again and again. It is this examination of the body as a framework that developed into Lee Bul’s exploration of utopian urban landscapes, their architectural designs, and consequently their shortcomings. I wouldn’t read this examination as a criticism from her side, however. It is more of a curiosity for her.

Made between 2015 and 2016, the highly symbolic Willing To Be Vulnerable – Metallic Balloon is a vast 17 meter-long sculpture resembling Germany’s Hindenburg Zeppelin, which crashed in 1937. It is a work that I have been captivated by for some time, having shown it previously at the Sydney Biennale in 2016. The work in the first instance is both ambitious and optimistic, capturing the futuristic nature of these vehicles that were a symbol of progress and modernity in the early twentieth century. On closer look, it’s material, a balloon made just of metallized and transparent film, reveals its vulnerability. At the Gropius Bau, Willing To Be Vulnerable – Metallic Balloon hangs in the atrium, forming a direct relationship to the building. The layout of the building allows all visitors to pass through the first floor in the atrium to experience the work and its detail from a new height.

These works each underline complications that are inherent to all attempts at utopian idealism, reflecting technical failure, fragmentation, and even destruction. On one hand, Lee is fascinated with the notion of our failings. On the other hand, she continues making work on this matter, without finding an answer for this phenomenon.

Lee Bul: Crash opens on 29 September 2018 as part of Berlin Art Week and runs until 13 January 2019 at Gropius Bau, Niederkirchnerstrasse 7, Berlin.