Mining a Counter-History from the Past: WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS and Subcultures in Kansas

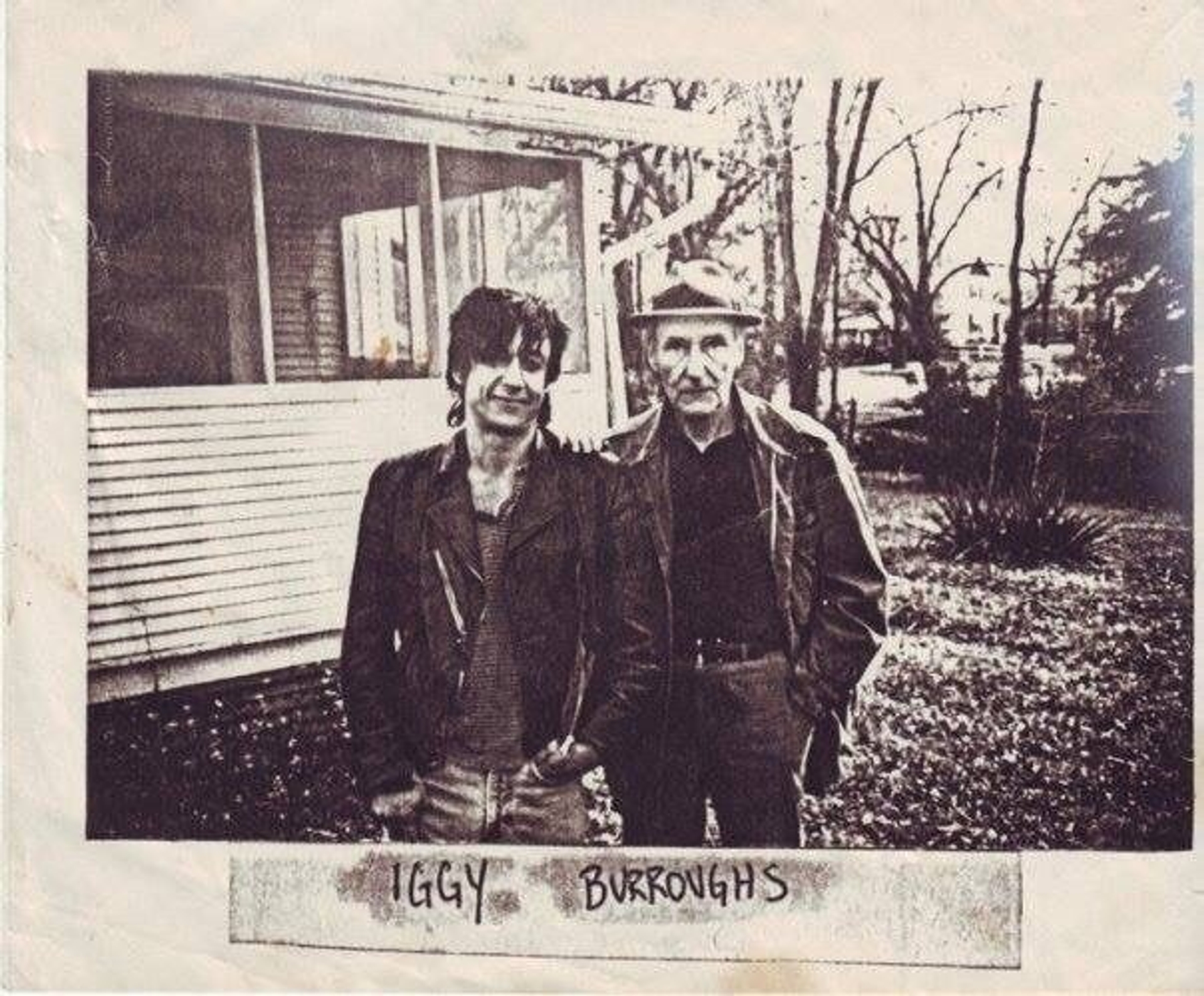

William S. Burroughs moved to Lawrence in 1981 with the encouragement of close friend, brief lover, literary executor and current bibliographer, James Grauerholz. He settled in a small bungalow located at 1927 Learnard Avenue. Just a couple of years after his arrival, Grauerholz describes Burroughs as becoming the genius loci, the prevailing spirit of Lawrence. Burroughs was attendant spirit of Kansas counter culture, and lived among the rows of clapboard houses and oak trees of the small college town until his death in 1997.

Burroughs's move seemed illogical to outsiders, who evaluated the relocation with an air of elitist presumption concerning Kansas. Accounts of Burroughs’s time in Lawrence suggest he approached life there with the attitude of a local. He shared his small home with three cats, maintained a garden in the backyard, and could often be seen walking with his cane to the local grocery store, Dillons. He built an Orgone Accumulator Box in his backyard and shot his beloved guns with the same fervor of any born and bred Kansan hunter.

Documentation of his life in Kansas can be seen in various lo-res videos have been achieved online. One video shows Kim Gordon and Thurston Moore of Sonic Youth and Michael Stipe of R.E.M. visiting Burroughs in 1995. In another video, Burroughs is shooting one of his infamous “Shotgun Paintings” somewhere in the country. A series of Burroughs’ “home videos,” shows Allen Ginsberg, Steve Buscemi, and Patti Smith in his living room. A low analog buzz plays underneath the clips as Patti Smith strums her acoustic guitar and sings along. Shot by Wayne Propost and edited by Michelle Tran, the videos show Burroughs and Ginsberg seated around the warm light of a kitchen table lamp, the former petting his cat and flipping through a magazine. Friends and local teenagers wander in and out of the frame, milling about among the counterculture celebrities. Smith’s singing and playing are edited as non-diegetic sound, carrying across clips where she is not seen. In these shots, Burroughs gestures emphatically about guns, or books, or whatever topic he was likely lingering on. The second part of the home movies are edited in roughly the same way as the first, with Smith’s music complementing the warm domesticity of the visual material. Near the end of both parts of the videos, Smith’s audio presence cuts out as Burrough’s voice briefly becomes the focus, his raspy speech adding to the personal and intimate nature of the fleeting moments.

Also among the digital detritus is a series of photographs of Kurt Cobain and Burroughs together at the Learnard Ave property. Cobain, an ardent admirer of Burroughs, visited during Nirvana’s 1993 tour. In a series of letter correspondences, Burroughs invited Cobain to Lawrence at the same time he declined Cobain’s request for him to appear in the “Heart Shaped Box” music video. During Cobain’s visit, Burroughs gave him a tour of the property, showing him his garden and even encouraging him to enter his Wilhelm Reich-inspired Orgone Box.

Four years prior, Nirvana played a show at the Outhouse, a venue whose status remains legendary nearly two decades since its closure. The Outhouse sits among the cornfields between Lawrence and neighboring Eudora, my hometown and the town where Burroughs and Nirvana’s collaboration “The ‘Priest’ They Called Him” at Red House Studios in 1992.

In 1979, Bill Rich — who later became the Outhouse’s promoter— began a local fanzine in Lawrence, Talk Talk. Soon after, he opened Fresh Sounds Records, an independent recording label, and began releasing cassette compilations and flexi discs featuring local bands. By in 1985, Lawrence promoters began hosting concerts at the Outhouse in response to the growing scene and the increasing police crackdowns of house shows.

The Outhouse then began its transformation into a full-fledged punk venue. At first, shows were primarily booked by KJHK, the University of Kansas student radio station, attracting college students and high schoolers alike. It was not long before a general community of maladjusted children of Evangelicals and conservatives began flocking to the fields on a regular basis.

The venue attracted negative attention shortly after opening. Neighbors complained of shaking windows during shows and flocks of teenagers showing up to their homes at 3am, asking to use the bathroom. Official complaints started coming to the county commissioner in February 1986, but local perceptions surrounding the venue became increasingly hysterical and as the venue grew and concerts became a daily occurrence — the pervasive effects of The Satanic Panic and the 1980s Culture Wars only exacerbating the problem.

Brad Norman directed the 2017 documentary The Outhouse: The Film (1985-1997), which constructs a genealogy of the venue and local scene through the lens of performers, concertgoers, and nearby neighbors who despised its very existence. The documentary portrays the esteemed status the venue held for not only local punks, but for legendary musicians whose preconceived stereotypes about Kansas often faded away within a single night at the Outhouse. Interviews featured in the documentary include the likes of Black Flag’s Henry Rollins, Bad Brains’s H.R., Fugazi's Ian MacKaye, and Fishbone’s Angelo Moore and Norwood Fisher, “It was like CBGB’s out there in the middle of the cornfield.”

Despite best intentions, the Outhouse did ultimately experience undesirable consequences of a subculture splintering into different groups –– punks, skinheads, metalheads, communist punks –– fights became common at the Outhouse. Racist skinheads infiltrated the scene and attempted to take over security positions at the door. Already a white cinder block building in the middle of nowhere Kansas, with no access to life beyond the cornfield, the threat of racist skinheads made the space even more dangerous.

That said, the Outhouse’s ethos was fundamentally opposed to any form of fascism and racism. In response to white supremacists invading the space, four anti-racist skinheads,colloquially called the “Four Horsemen,” assumed roles as de facto leaders and formed “Skin Heads Against Racial Prejudice” (SHARP) in 1989. Not only were they anti-Nazi and anti-racist, but violently so. If anyone was caught exhibiting racism at a show, SHARP would beat them up, throw them out, and cut up their cherished Dr. Martens.

As a space made by, for punks, the Outhouse was radically resistant to hegemonic discourses and solutions. Internal problems were handled from within the community, never capitulating to outside policing. Routine concertgoers, bonded through the physical space and their mutual disdain for mainstream culture in Kansas, took care of one another and supported each other’s art. It was not merely a space for degeneracy or pessimism, but instead a space in which one could imagine a future world. “Punk rock style may look apocalyptic, yet its temporality is nonetheless futuristic,” José Esteban Muñoz writes, “letting young punks imagine a time and a place where their desires are not toxic.”

Many of the cornerstones of American punk and post-punk passed through the Outhouse over its 12-year reign. Black Flag, Circle Jerks, Bad Brains, Fugazi, Sonic Youth, Nirvana, Green Day, Rollins Band, and Fishbone are just some of the names who paid a visit to that small box in the middle of a cornfield. By the early 90s however, the Outhouse had already departed from its primarily punk and post-punk origins. Metal and Ska became more common as punk was becoming obsolete nationwide. The community, which at times had quite literally burst beyond its means, declined with the venue’s genre expansion. The decline was furthered by the concomitant mainstream success of Grunge and the rise of new and diluted genres like Pop-Punk.

By the mid-90s, the Outhouse ultimately whitewashed its interior walls, effacing years of sedimented graffiti in order to make it a more “neutral” space for any form of “alternative” music. However, without the definitive aesthetics or touchstones which punk subcultures had provided the space with for so long, the space became less and less suitable for any community to form around underground music. The space was later painted black, and crowds became older and smaller with time. Without a central image, the Outhouse slowly died out. On January 4, 1998, just a few months after Burroughs’ death, the venue hosted its final show and officially closed its doors.

Burroughs, himself, was not unfamiliar with the Outhouse. Of course, artists who paid him a visit often did so at the same time they were playing a gig there. However, his relationship to the scene was much closer than that. In 1983, Burroughs wrote the lyrics for “Old Lady Sloan,” a song by the Lawrence punk band The Micronotz. He also released multiple spoken-word records with Fresh Sounds Records, promoter Bill Rich’s independent label based in Lawrence. There is no evidence of him attending a show at the Outhouse, but there are many images of him making his shotgun paintings on the property.

Now a strip club, the Outhouse has not hosted a concert in over two decades. However, like other histories of Lawrence — whether it be its status as the center of the anti-slavery “Bleeding Kansas” movement or its storied protests of the 1960s and 70s — the legacy of the city’s subcultural practices at the end of the 20th century continue to play out in the present. The punk sensibilities of creating alternative spaces, communal and mutual forms of care, and fostering community through live music which were crucial to the Outhouse are also key to a radically new scene which has emerged from the isolation of the pandemic.

Unlike the Outhouse, whose scene operated in a sort of vacuum free from cares about the outside world, today’s new scene expands beyond any original sense of genre, community, or venue. Not limited to the DIY punk and hardcore scenes often associated with the Midwest, many DJs, rappers, experimental musicians, and post-punk bands define the new sound of Lawrence. That said, like many punk or DIY scenes, it embraces amateurism, growth, performance, collaboration, movement, and fluidity, but flatly rejects gatekeeping. At the same time, it embraces values of intimate community-building, and collapses the local with wider movements of music, as local artists routinely open for bigger acts like Club Eat, Yves Tumor, Coucou Chloe, AceMo, Machine Girl, and Hook at shows in Lawrence.

photo by Phillip Pyle

photo by Phillip Pyle

photo by Phillip Pyle

photo by Phillip Pyle

Like the Outhouse, the current community is, in a way, performing utopia. Taking from the Frankfurt School idea that utopia is above-all a critique of the here and now, José Esteban Muñoz constructs an idea of the utopian performative in his book, Cruising Utopia. Muñoz is concerned with the ways in which queer and punk subcultures enact ways of doing that are always in progress, never finished, and are based on shifts between acts of repetition and reiteration. “Utopian performativity is often fueled by the past,” Muñoz writes, “The past, or at least narratives of the past, enable utopian imaginings of another time and place that is not yet here but nonetheless functions as a doing for futurity, a conjuring of both future and past to critique presentness.”

Lawrence subculture today seems to do just that — to (un)consciously garner its methods and drives of subversion from the city’s historical legacy, to imagine a future which obliterates divisions between genres, groups, spheres of existence in a way that critiques the present. Like the Outhouse, it resists the threat of cultural hegemony affecting all subcultural spaces while repudiating the particular form of suburbanization impacting Lawrence today. Built on a foundation of interpersonal and mutual forms of care, support, and collaboration, the scene is constantly evoking an affect which will long outlive its life, and which will stay with those who will inevitably move out of the area to bigger cities. “This potentiality is always in the horizon and, like performance, never completely disappears but, instead, lingers and serves as a conduit for knowing and feeling other people.”

After all, did Burroughs himself not find a bit of utopia in Lawrence, too? After a career of writing on dystopias, drug-fueled apocalypses , surveillance, and urban degradation, Burroughs began exploring utopias and the more compassionate visions of his mind in Lawrence. There, he opened a new and sympathetic facet within himself and became somewhat of an animal activist. Concerned more with animals than with humans, Burroughs’ utopic imaginings were posthuman, in a way — he would dream of hybrid animal species, creatures which may one day evolve into being. Although not utopic in an anthropocentric sense, this shift in Burroughs’ thinking and writing was nonetheless utopic when compared to his earlier envisioning of hellish futures and vitiated landscapes. Like punks stumbling upon the nondescript building of the Outhouse in the 80s and 90s, and today’s scene gravitating toward various venues such as The Bottleneck, The Toilet Bowl, and Replay Lounge, Burroughs found and staged utopia in Kansas, among the historical remnants of past utopic efforts and the stray cats that wandered about his property.