Monstrous Thoughts: Philosopher EUGENE THACKER on the “New Golden Age of Horror”

When René Descartes, sitting in his armchair in Leiden in 1641, invites his readers to meditate alongside him, you get the sense he could do with the company. The Meditations are considered the founding text of philosophical rationalism, but on a psychological reading of the “radical doubt” that follows, the primary motor of Descartes’ project is paranoia. The cloaked men in the yard might be robots, his senses deceptive, and, most famously, everything a dream from which he is only just awakening. All of which culminates in a thought experiment. Descartes asks himself whether it’s possible that he’s being deceived by an evil demon – a character he lifts from theology, but which we’d now tend to associate with the horror genre.

Modern philosophy is born in an encounter with horror. The point of Descartes’ demon isn’t to pose a tricky brain teaser – it’s that thought quickly runs up against its own limits, and that the experience is somehow monstrous.

In his Horror of Philosophy trilogy, the philosopher and media theorist Eugene Thacker explores not only this horrifying nature of philosophy, but also the philosophical nature of horror. Thacker thinks that, if read the right way, Gothic tales and Grindhouse hits aren’t only scary – they can help us question the limits of human knowledge, experience, and selfhood. Take the first lines of a famous H. P. Lovecraft story: “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far.” For Thacker, The Call of Cthulhu (1928), no less than Kant’s Critique (1781), is a meditation on human finitude.

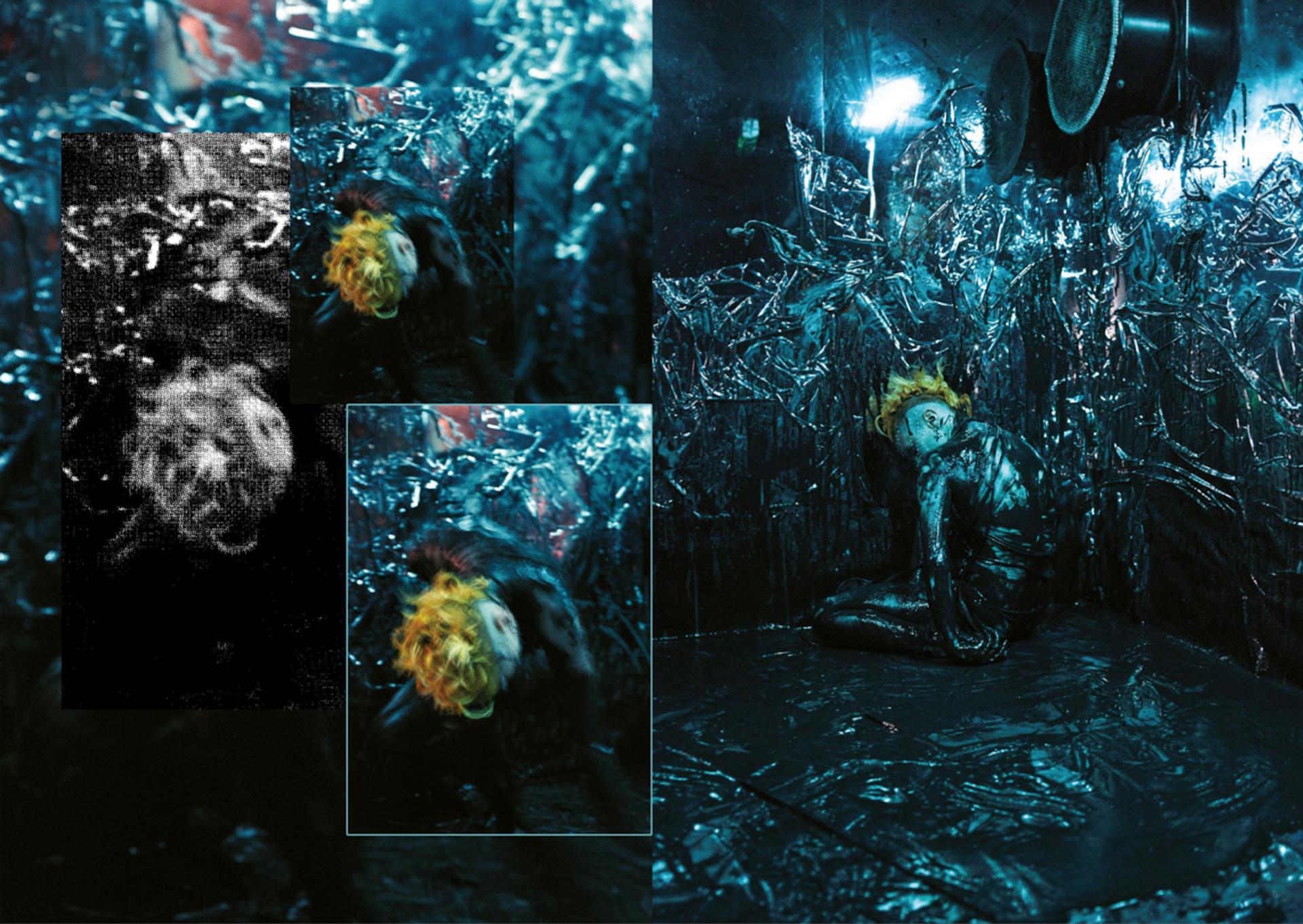

Earlier this month I asked Thacker to explain this disturbing overlap, whether horror really has entered a “new golden age,” what he thinks of the Anthropocene – and, of course, for a few of his favorite recent flicks. Accompanying the interview are images from the fourth issue of Sort Studio, a multidisciplinary project specializing in noise music, cyber-sex, and all things goth, to which Thacker contributed an essay.

Daniel Beatty Garcia: Perhaps we could start by talking a bit about what you mean when you talk about horror.

Eugene Thacker: The kind of horror I’ve always been interested in is more about creating a mood or an atmosphere than creating a narrative, and really more idea-driven than story-driven. “Cosmic horror” writers like H. P. Lovecraft are less interested in shocking you than with the boundary between the natural and the supernatural, or the limits of our ability to know things about the world and our place in it.

In your work this incomprehension in the face of the nonhuman world is the nexus between horror and philosophy.

There’s a synergy between that kind of cosmic horror and certain philosophers who also explore the limits of our understanding. When we think about philosophy we usually think about some sort of picture of the world, and when we think about philosophers, we think about a person who knows, and who’s going to tell us how to live our lives and how to exist in the world and so on. But some philosophers are more interested in asking questions than giving answers, and finding compelling ways to articulate confusion.

These philosophers often write in a gray zone between philosophy and literature, a kind of poetics in the sense of experimentation with form that allows them more freedom and flexibility. So I thought: “Wouldn’t it be interesting if I went back and I read horror stories as if they were philosophy? And what if I read philosophers like Kierkegaard, Schopenhauer, or Nietzsche as writing horror stories?” It was playing with that kind of creative misreading that allowed the project to take shape.

So philosophy and horror are exploring the same questions, and the same predicament. By treating horror as in a sense doing philosophy, aren’t you closer to post-analytic philosophers like Stanley Cavell, who studies the intersection of literature or film and philosophy, than to classic horror theory – which is more influenced by psychoanalysis?

For me, the most interesting horror criticism isn’t necessarily academics from film studies writing about horror films. I’m more inspired by theologians writing about religious experience, for instance. They aren’t talking at all about horror film, but there’s something in what they are talking about that resonates with the kind of films that I’m interested in.

I guess it’s no accident that so many characters or stories from horror are biblical in origin – whether it’s possession, demons, or the devil himself.

That’s the more politically orthodox side to religion. That can become a source for the horror genre, but also if you look, say, at mystical traditions, they’re simply using the terminology of religion or theology to talk about the same structural issue, which is a horizon to human understanding.

In that sense you could say that the ancestor of modern horror is negative theology. Despite the historical breadth of your sources, your understanding of horror as confronting something almost existential sounds quite ahistorical: this is something unchanging, the limits of human knowledge – if not the limits themselves, then the fact of there being limits. How can a theory like yours account for the fact that suddenly horror seems to have taken on this entirely new cultural center-stage position – the supposed “new golden age” of horror?

You do have a point. But my approach is to entertain both the idea that there is something specific to the now, and also that this is how it’s always been. For instance, with the overwhelming burden of awareness that we have today about global climate change, and the delirious topsy-turvy carnival of the political scene, it’s not hard to make the argument that horror is responding to the state of the world by acting like a mirror.

That’s fine, but then you can go back and look at another boom that occurred in the late ’90s when independent horror film came on the scene. That was a different kind of confusing period with different kinds of things happening. Then you can go back to the late ’70s and early ’80s when horror became mainstream. Hollywood took notice of it, and it crossed out of the confines of genre, but yet again you have a different period when this is happening. You can go all the way back to the 18th century, the peak of the Enlightenment and the emergence of the Gothic novel as a sort of underbelly of the costs of instrumental reason. I think the form of that is consistent, but the content of it might change depending on the time and the cultural context that you’re looking at.

The most obvious example of horror that privileges mood over story is the Gothic – Edgar Allan Poe even says somewhere that every single word in a story should go towards creating an atmosphere. Are there any contemporary films that you feel are doing this?

One film I saw recently that I was really taken with is Hagazussa. It’s part of a style or tendency in horror film that is all about slowness, stretching out time, and it’s all about building that mood. It does use some of the tropes of horror film, but it’s more about putting you in this almost hallucinatory, trance-like state. Everything is sort of dilated. You could call it slow horror. What it does is it creates this deep time sense. You get the sense of the human being as just one component in the bigger world – and not even the most significant one.

Other people are calling this tendency “post” rather than slow horror, because it’s abandoned jump-scare tactics entirely. There are even directors that used to be associated with other horror waves that are now supposedly “post-horror.” Olivier Assayas and Claire Denis used to be associated with the New French Extremity, but now they’re doing films like Personal Shopper and High Life, both horrors in theme – ghosts and human experimentation respectively – but slowed down almost to a standstill.

I wouldn’t call it post-horror. What’s more interesting is that it might be transforming the genre itself into something else. And you see some of these motifs historically: in Tarkovsky, in Ingmar Bergman’s films – Through a Glass Darkly especially – all the way back to German expressionism.

It’s also there in a lot of Asian horror. There’s a lot of film coming out of South Korea that I find really compelling. There’s a recent film called The Wailing, and another called A Tale of Two Sisters. Both of these not only have that slow horror feeling about them, they also explicitly deal with a dilemma: is something supernatural happening, or is it all in my head? You have a split between the scientific and the religious, or the psychological and the supernatural, and an uncertainty that’s held all the way through to the end. That’s really hard to do, and it’s another example of just holding or inhabiting uncertainty and confusion and not trying to resolve it too easily.

That sustained uncertainty – what the literary critic Tzvetan Todorov calls “the fantastic” – and that slowed down dread seem to be spreading. Part of the movement comes from the other direction – other genres incorporating horror tropes, directors like Nicolas Winding Refn using the Giallo horror aesthetic.

Absolutely. Crime thrillers like You Were Never Really Here, Lynne Ramsay’s film. These are out of genre, but you can see how they’re importing that same sense of slow, almost lyrical dread. There’s again this zoomed out sense that these characters aren’t really making decisions. There’s some other nebulous set of forces, and the human beings are just puppets. That it’s leading them to some end.

Sometimes this is expressed visually. I just watched this TV show, The Terror. It uses a technique you see a lot in film in which you cutaway to the landscape. The contrast is between the smallness of human beings – the intensive little human drama happening aboard this ship – and then this vast indifferent landscape that is surrounding it. Again, there’s some resonance between that sort of experience and earlier accounts of mystical experience or religious experience.

Still: "The Terror"

Couldn’t this experience of our smallness in front of the vastness and incomprehensibility of nature be a positive one? Poets have called it “the sublime.”

Of course, for some philosophers like Kant there’s a happy ending to the story, because human reason is able to recognize this limit and then say, “Well, okay, that’s off limits, but within this domain we can obtain a certain level of mastery.” It’s interesting to quote somebody like Lovecraft in juxtaposition to Kant, because they’re both talking about that distinction between the world in itself and the world as it appears to us, but Lovecraft goes all the way, and says that there is no moment of redemptive reason.

Bruno Latour has an interesting take on this. He points out that if new research into the Anthropocene shows the nonhuman world to be marked at every point by us, human influence has “scaled up” to the extent that we are no longer so small compared to nature. So experiencing the sublime, that feeling of being dwarfed, becomes impossible. What this shows, for him, is that what we took to be an unreactive or indifferent nonhuman world was in fact sensitive all long, and that we are enmeshed in it at every point.

There’s some interesting things in those kinds of theories, but they are still heavily anthropocentric. I think one of the lessons of the Anthropocene is that there seems to be a species-specific solipsism that we’re so stuck in that we’ve actually named an epoch after ourselves.

What are Anthropocene theories missing?

They usually ignore two kinds of indifference at work. The first is that we can call the world whatever we want and measure it however we want – there’s still the unbreachable opacity of the something-else out there reacting or not reacting. The second kind of indifference is more specifically contemporary. If you look at the tradition of the Gothic novel, there’s a tension between science and religion, and often that boils down to a conflict between the rational and the non-rational. Now added to that is something we could call “cold rationalism.”

Every day you can look at The Guardian, and there’ll be some article with a lot of facts and data about the amount of biomass we consume, or the sixth mass extinction, or whatever. We’re inundated with this big data level of horror. It’s not so much a failure of science – the science works almost too well. What it reveals to us is exactly how indifferent the world is to all of our attempts to master, or control it, or produce knowledge about it. Authors in the early 20th century like Lovecraft and other “weird” authors already understood that the more horrifying path was not anti-science, the non-rational. Far more horrifying is what science will reveal.