Screen Protector: For critic A. S. HAMRAH, streaming is a utility, television is an appliance, and the more movies merge with other media, the worse it is for everyone.

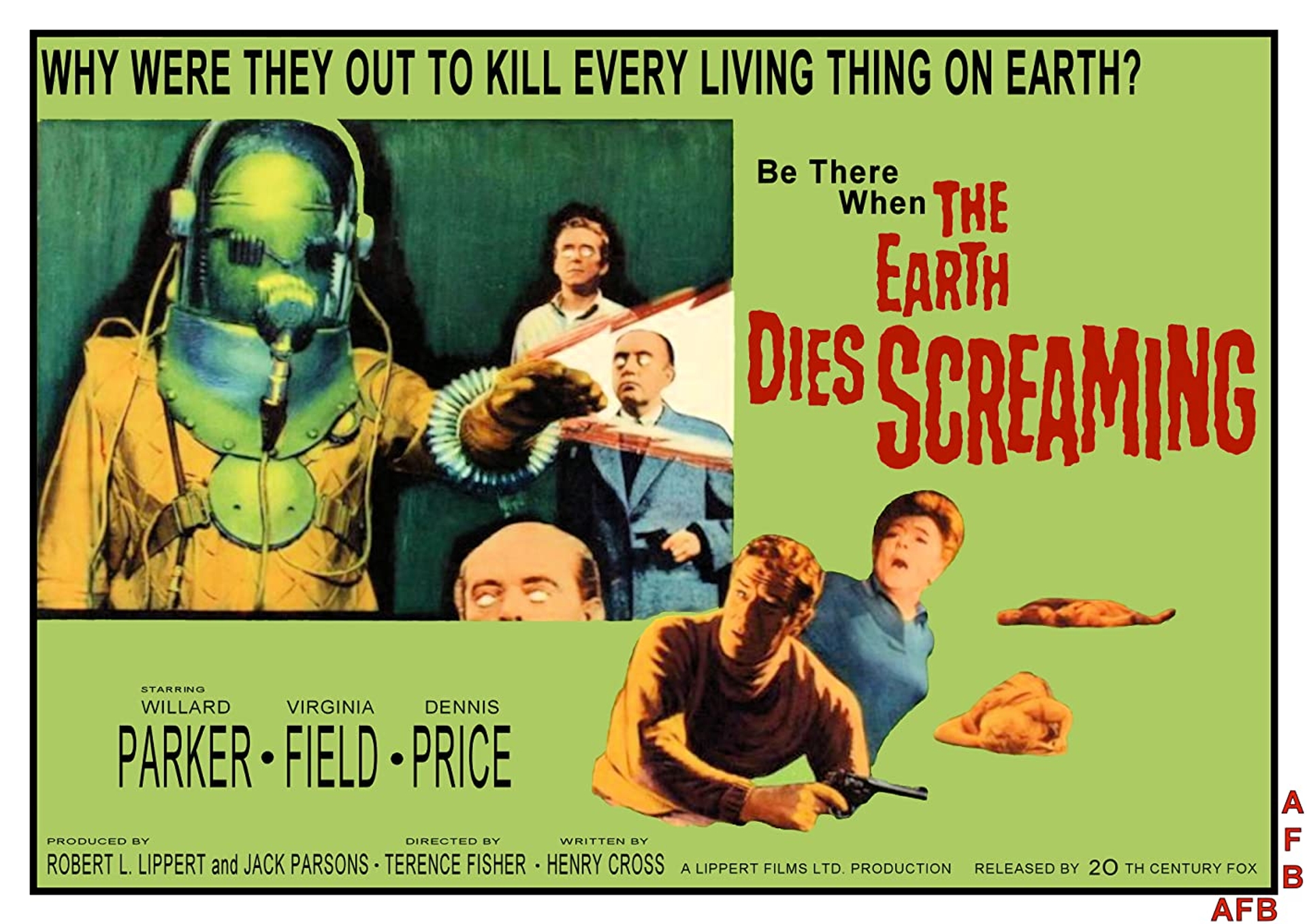

Movie theaters closed. Film festivals canceled. Openings delayed. The most resolute and perceptive American film critic writing today is A. S. HAMRAH, and no radical alterations to his industry will silence him. And that’s fortunate for us, for we have no finer guide to hack through the jungle that is modern cinema, with its endless array of screens and streams, and deliver us more intelligently to the other side. The Baffler shrewdly just put Hamrah on their masthead after he spent 11 years on n+1’s. His collection of reviews, The Earth Dies Streaming: Film Writing, 2002–2018, came out a year and a half ago to rave reviews, and is about to go into its third printing. “Rotten Tomatoes” it is not. The forecast in the book title has never looked more likely – but it isn’t inevitable. Filmdom has no bigger champion of movie theaters than Hamrah. And that’s fortunate for them.

The Fonz jumps JAWS.

Wes del Val: You’ve watched several thousand hours of movies at this point in your life. Initially probably like most other kids, for the pure entertainment and/or consciousness-expanding aspects of it, and then as a professional critic meditating upon what you’ve seen. All of this time sitting silently before a screen, writing your takes on what you’ve seen from an international variety of directors – has it given you a particularly enlightened perspective from which to view the extreme state of the world right now, and the current solitary existence of many of its inhabitants?

A.S. Harman: I hope what I write isn’t “takes.” “Takes” to me means short-form bursts shared on the Internet, initial reactions that people for some reason think they have to get out in public immediately, without hesitation, right after they’ve seen something—yawns or sneezes of the keyboard. You could say “takes” just means “reaction” or “opinion.” Then, when the takes by definition have to be hot, it’s going to be nihilistic and crummy. If all criticism is just takes now, at least I serve mine cold.

The novelist J. G. Ballard wrote, in one of his novels in the early 1990s, that “in the future, everyone will need to be a film critic to make sense of anything.” That day has arrived. In my case, I was able to predict an aspect of this future in the introductory essay to my book – not just because I had been such an inveterate filmgoer, and a writer on the margins for so long. I had also been a movie theater projectionist and a semiotic brand analyst for the television industry. In both those jobs the amount of material you must see and process is staggering, but in different ways. One is mechanical and physical, and the other is cultural and theoretical. They each trained me to look at things in different ways, but in ways that are linked.

Once you can distinguish the good from the bad, you can understand ideology and all the lying and mythmaking and the corrupt ways images are put to use. I don’t mean that cynically, by the way, I mean that all that deepens you and helps you navigate a culture defined by the making and proliferation of images. The cinema taught me about parts of the world I will never visit – not just about geographic places, but about levels of society the movies helped me to recognize in the world when I encountered them. I could examine things in that light. The movies taught me to empathize with perspectives outside the places that formed me.

Among the arts, why is film still such a remarkable balm for the masses? Notice all the lists over the past month being circulated unceasingly on social media. I know, I know, there’s also “prestige TV” available to everyone today, but I feel many people still wax more passionately about movies than they do television shows, from any period. Is it the bigger the screen, the bigger the star, the deeper the impact?

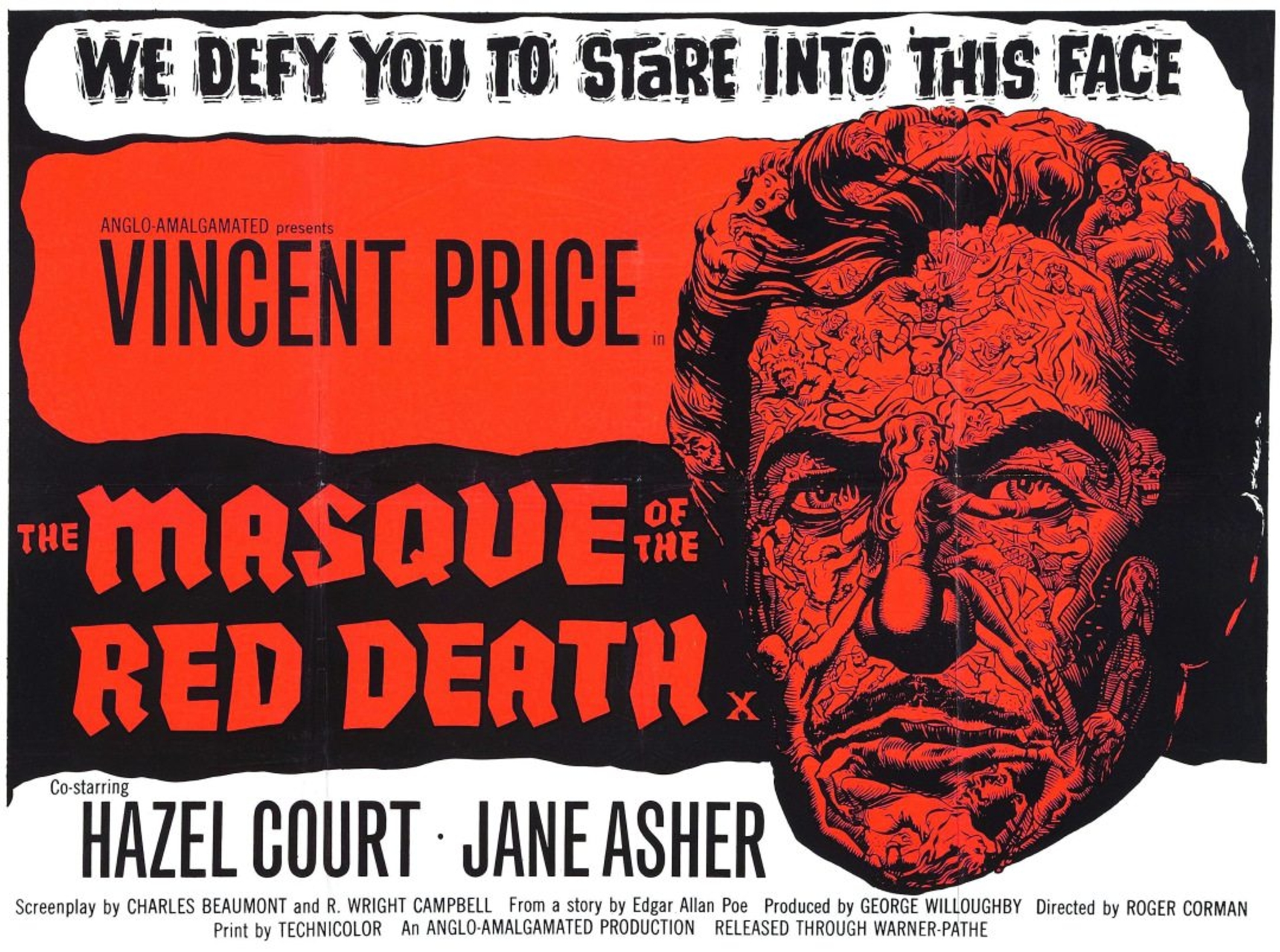

It’s because cinema is not disposable as much as television is. I would not say it’s a balm or an opiate. It’s a way to figure things out. Right now a lot of people have turned to movies to help get them through the disaster of the virus and of lockdown, and of all the death surrounding us. People are watching and discussing films about viruses, isolation, and systemic collapse, from Contagion to The Masque of the Red Death. Not just movies about plague and quarantine. I mean people are turning to things they know have more depth, more meaning, and are more resonant than TV. The crisis has, obviously, revealed the vast immiseration capitalism has created and exploits. We now see, very starkly, how imprisoned we are in this system, one that demands we work 24 hours a day to make the rich even richer, even if that means we lose our homes or in the case of many low-wage workers and medical professionals, die on the job.

Television does not help us understand any of that. Or if tries to, it sentimentalizes it. It’s novels and movies that show us how things are, things that are thoughtful and reflective. TV is just a stream of replaceable, empty nonsense, even in its so-called prestige form. Because the crisis is so intense, however, it is a paradox that now it is hard to concentrate on the kind of thinking we all have to do. Movies help with that more than novels, I think, because they focus concentration more for a set amount of time, and they feel less lonely right now, when many people are home by themselves. Novels need more peacefulness. It’s harder to read now because reading is a choice to be alone. Now being alone is not a choice.

TV just seems so dumb. Video games are better. For a lot of people, video gaming will probably just take over now, pushing TV shows out of the way. I can’t watch TV at all right now. TV news has eroded so much over the last 40 years that it’s worthless. When the news becomes more cinematic it’s better, but not in the way TV usually thinks of “cinematic.” Television struggles with the concept of the cinematic. People in TV think cinematic means a Lord of the Rings movie. I was riveted to the whole uninterrupted half hour of the CNN interview with the mayor of Las Vegas, which was like a Shirley Clarke film or something. I came across it on social media and then watched the whole thing. If it had been just another segment in the 24-hour news feed on TV, it would have hit me differently, I wouldn’t have paid such close attention to it. I watched it three times. It’s just so shocking. That kind of long-form exposé is more like a movie than TV. It was basically just one shot of this woman, an elected official, for an uninterrupted half hour, cackling nervously while she suggested hourly workers go back to work in casinos where the city would allow anyone in.

What is your definition of a movie and how much of a factor does the traditional time span of one-and-a-half to three hours matter for what qualifies a filmed production to be called a movie? For instance, no one would disagree that there was both a Sex and the City television show and two movies but look at the standard length of the movies compared to the totality of the series. And there are “episodes” of Star Wars but no one would call that a TV series. Is it all just structured to milk as much money out of fans as possible, and if they thought the financial support would be there the studios would pump out more regardless of what it’s called or where it first plays?

A movie is a filmed story or set of images that takes place over a certain amount of time and is best seen in large-scale projection—on a big screen. Entertainment conglomerates will exploit any successful property across all media, as has happened with those two examples, just as there are oil wells in the desert and in the ocean, and there is fracking and natural gas. I don’t think those two properties have really been successful or satisfying to audiences in the medium they were moved to, whether it was moving Sex in the City to movies or Star Wars to TV. If people watched episodes of TV shows in a movie theater, they would see how empty they are. Because the mise-en-scene is not there, it’s all big heads, just pictures of people’s faces cut together. It’s all eating in restaurants, driving cars, looking at computer screens, as Werner Herzog said movies were becoming. But, instead, when movies are boring, it’s about spectacle, it’s about extra scale that movies don’t really need – I mean like Transformers movies or superhero movies. There is this misunderstanding of scale inherent in those, and they deliver a different kind of boredom the more they try to be exciting, because there’s so much redundancy. TV exists to comfort people and movies to wow them, the way each is, or was, configured in contemporary Hollywood film production.

How much is truly “lost” watching for example 2001 or 1917 on your sideways phone in bed rather than in a theater? Or is it just a matter of knowledge vs. experience vs. convenience and what each person is seeking depending on their current mood?

Almost everything is lost by watching movies on a phone in bed. Movies depend on large-scale projection, which is a fact people now want to ignore. They have acquiesced to the feed. Watching movies on a phone or tablet or laptop is like seeing pictures of art in a book. Seeing movies in a dark theater is already like being in a kind of dream state. So I can understand why people want to watch them in bed.

But doing that is maybe a waste of time. The question of why people want to do that is what’s more interesting. They’d be better off just to get some sleep. If you can’t sleep, get up. Don’t lie there with this IV drip of images. Where screen-addiction meets laziness, that is where our culture dies. It’s terrible how defeated people are. Something like Quibi was invented for insomniacs who hate their lives and want to burn their eyes out. Or, it was invented by people who would never do that themselves, so that they could cynically exploit people who will. Whenever I couldn’t sleep and turned to my phone to watch comedy clips or something, I just felt bad after, like you might after cheap drugs. Do you think television executives like Jeffrey Katzenberg and Meg Whitman lie in bed at night watching TV shows on their phones? They don’t. They are the pushers getting wealthy off your depression.

Since so many people today do indeed watch films on small screens in a variety of settings, what do you think that portends for the next 20 years of movie-making and the culture surrounding it?

It’s hard to say right now. I think the Covid crisis is going to permanently reconfigure Hollywood and all film and TV production in some way, everywhere. People are watching a lot of movies these days at home, and I know I miss movie theaters and so do lots of other people. But I don’t think anyone is sitting at home saying to themselves, “If only I could get out of the house and go see a Tom Holland movie. Why can’t I go to a movie theater and see Charlize Theron and Robert Downey, Jr. right now?” I mean, who gives a fuck? That “Imagine” video Gal Gadot put together was so telling. These clueless celebrities are not made more appealing by having bedhead and mouthing a song everyone knows. They have no aura, nothing special, just money and skincare regimes that are breaking down. The blockbuster stars are irrelevant right now.

I think there is going to be a lot more green-screen cinema, and movies made at desks in computers, and streaming is going to become more and more important, paradoxically just after the moment last year when people began wanting and seeking out better movies, instead of franchise movies. The success of Parasite, with its violent criticism of the 1%, was surprising. It indicated a change, even though many more people saw the Avengers movie. So I expect there could be a major retrenchment that will be very right-wing and dumb, as studios all go as Disney+ as they can, even though their bottomless amount of blockbuster content seems dated now.

The more movies and TV merge into one medium, the worse it is for both of them. Movies because they are diminished by that, brought down, and forced to adapt to TV standards. TV because it just adds to the lie that TV is something more than the transmission of live events, or recently recorded events.

“Quibi was invented for insomniacs who hate their lives and want to burn their eyes out. Or, it was invented by people who would never do that themselves, so that they could cynically exploit people who will.”

Movies clearly aren’t going anywhere, but how often do you stop and think about how many human hours went into producing, directing, lighting, editing, and, and, and… each and every single movie we all so blithely scroll past while pointing out that we can’t find anything to watch?

In the virtual content mound, human effort is meaningless. It’s all just junk you can swipe by or not, just as on dating apps humanity is reduced to a swipe of approval or disapproval. Because of this crisis, movies could go away as new productions that are shown in theaters. That could happen. It all depends on how long this lasts, if a vaccine is discovered, if widespread testing becomes available and affordable. We do not live in a civilized country. Large corporations would prefer you to stay home and pay them monthly subscription fees, even as their servers destroy the environment. Streaming is a utility, television is an appliance. For Disney, it’s better if they are like Con Edison, and they send everyone on the planet a monthly bill. They don’t even send one, though. They extract their fee from your bank account hoping you won’t notice, that you’ll forget that happens every month.

Does unlimited streaming, when it’s so easy to start, stop, and move on from movie to movie or show to show, place a different emphasis on beginnings and/or endings?

The end point of a movie is what makes it. That’s why endings are so hard. A bad ending can really ruin a film. TV, on the other hand, does not have endings. It goes on and on. When a show ends well, like The Sopranos or Seinfeld did, people get mad at it. Game of Thrones struggled so much to end, it was sad for a lot of people to watch, I think, and then they left those coffee cups and water bottles on the set when they were shooting, broadcast that, and had to go back and digitally erase them from the shots. And all the pieces before the last season aired, extolling how great it was. And then viewers got that.

TV fans prefer the shows they like to just peter out and fade away, and then to go into syndication. There’s this presumption that it will never really go away, even if there is an identifiable “jump the shark” moment. That moment becomes part of the process of it fading away. A movie is new each time you see it. TV really is wallpaper. You can see a movie you didn’t like the first time you saw it, and have a completely new experience. It can be a real revelation. It tells you you’ve changed, you’ve grown, you know more and are more understanding. TV, when re-watched later, tells you how stupid you were to like it in the first place, and how you wasted your time. That’s why a lot of sitcoms play on the idea of pointlessness and stupidity. Or just repetition. It’s the same each time you go back to it.

I want to talk more about the specificities of writing critically about film, rather than say theater or dance. All three show human beings in motion, mostly featuring planned stories as characters, and there’s speaking in theater just like in movies. Is the primary difference that a movie is shown on a screen (that again) and is not live and is there key critical language exclusive to writing about film and not the other arts?

There are technical terms in film production that critics sometimes misuse, like “jump cut” or something. You find words used in strange ways in movie reviewing, like “zoom” or something. That’s trivial, really. Technique, though, is not something many critics care about. They care more about plot and message and judging if acting is good by their standards. So often you will read reviews and you can’t tell if the movie is in color because the critic you’re reading doesn’t care about what it looks like, just what it’s saying. I mean, they assume you assume it’s in color, of course, and that contemporary movies have got that figured out and it’s something you don’t have to notice or mention.

Each medium has its own form, its own language and there is a subsequent discourse around each that becomes calcified over time. Projecting shadows from moving filmstrips onto a large screen is not the same as live theater or dance at all. The images are ghosts, really, and they exist in the space of the projector beam overhead. They affect us optically because we are watching shadows of pictures shown at a certain frame rate. Projecting movies digitally retains that as a memory in the audience. You have to see it through a new kind of memory because it looks different on screen and has a different effect on the eye and the brain. It doesn’t have the depth or the fragility that is so enjoyable and satisfying with film, the shimmer that creates movie stars and which affects the viewer emotionally. Digital is too clear, but that’s what the generation of Lucas and Spielberg in Hollywood wanted movies to become, essentially a storage medium without material flaws. And then they made the mental leap that someday people will only know digital and have no memory of actual film projection. At this point it’s impossible to understand why they wanted all that. It’s wrapped up in their desire for immortality, this overweening idea that tech people and baby boomers share, that they should not have to die, and that they don’t have a cultural expiration date.

The wealthy donors who support dance and theater are not interested in criticism, criticism is for readers, not for donors. It seems to be that for a large part of the audience for dance and theater, what they are interested in is virtuosity. In classical music, in opera, in the highbrow forms of theater and dance, this wealthy audience wants an experience of discernible quality that they can recognize and discuss because they have seen it and heard it before. The same as American Idol. They are comparing different performers in the same roles. In film criticism, there is still a lot of room for other things; it’s more free, it can get more out-there. Film festival culture tends to move filmmaking into these more empyrean realms, however. It becomes more niche and highfalutin because of the donors and the opening night parties and so on. And then film critics want to be part of that and it makes them timid about criticizing what they see.

Baby Yoda, Internet sensation.

“For Disney, it’s better if they are like Con Edison, and they send everyone on the planet a monthly bill. They don’t even send one, though. They extract their fee from your bank account hoping you won’t notice, that you’ll forget that happens every month.”

How are you critics able to sit for such long spells and watch so many films a day? I’m serious, I’m always amazed at your stamina. Sontag surely never missed a chance to mention marathon sittings. Are we back to why the vast majority of movies are around two hours long simply because of what the average human wishes to endure?

It is unhealthy, these marathon viewing sessions, but I like writing about things that have an endurance-test aspect to them, though now that is becoming trivial because of binge-watching and listicles. You have to get up from binge-watching TV, too, just like you should get up instead of watching things in bed when you can’t sleep. I’ve written pieces in which I’ve had to see every film that was press-screened for a festival or every film about a certain subject that came out over a certain period of time. I watched them in movie theaters, not on the couch at home. That’s just not good for you physically. Neither is. It’s a habit cinephiles get in when they’re young, and then it takes a toll.

The French filmmaker and critic Luc Moullet wrote something I read last fall that has kind of haunted me: “Seeing too many films eats you up.” I think that’s true. The movies, we were told, are like a rollercoaster ride—that was the blockbuster-era approach and goal. I think that era just ended this March. But film criticism is a real rollercoaster ride, too, let me tell you. I was glad Martin Scorsese, also last fall, finally said theme parks and movies are two different things. Film is durational and time-based, you have to experience it that way or you are just kidding yourself about it. It takes a certain amount of time, there’s no getting around that. If you watch it in bits you are stealing something from it instead of experiencing it.

That’s one reason the art world loves movies – they can rob them – and that certain kinds of theater directors do, too. They want to chop movies into bits, and it upsets them that the cinema has been so dominant for the last century or more. They pretend to criticize it by exploiting it. That’s why non-cinephiles and art critics liked Christian Marclay’s The Clock so much ten years ago, and cinephiles were largely indifferent to it. It was something cinephiles had already thought themselves, so they didn’t get much from seeing any of it. The Clock cut the cinema into random bits that all had time in common, literal pictures of clocks, then kidded the cinema’s durational element by making the whole thing 24 hours long, so that no one could watch it in one sitting. It’s so childish and obvious.

It’s perfectly understandable, though, because even filmmakers want to enact violence on the cinema itself, as a form – to cut it up. And some film critics do that, too. There’s a good way and a bad way to do it. You have to do that, like pruning a tree so it grows better. Trees get viruses like people do. A virus shut down all the movie theaters and film production in the world. Viewers at home are now taking cinema like it’s the cure.

CONTAGION promo montage.