Super Modern MUGLER

Thierry Mugler created his first collection – “Café de Paris” – in 1973, but it was in the 1980s that he rose to international prominence as a designer, becoming known for the dynamic silhouette of his womenswear, its pinched waistlines and prominent power-shoulders. Before Paris, Mugler was “a lonely, bewildered child, borderline autistic, borderline anorexic . . .” growing up in Alsace, where he was “saved” by a training in classical dance that would infuse nearly three decades of body- and movement-obsessed work in fashion and fantasy.

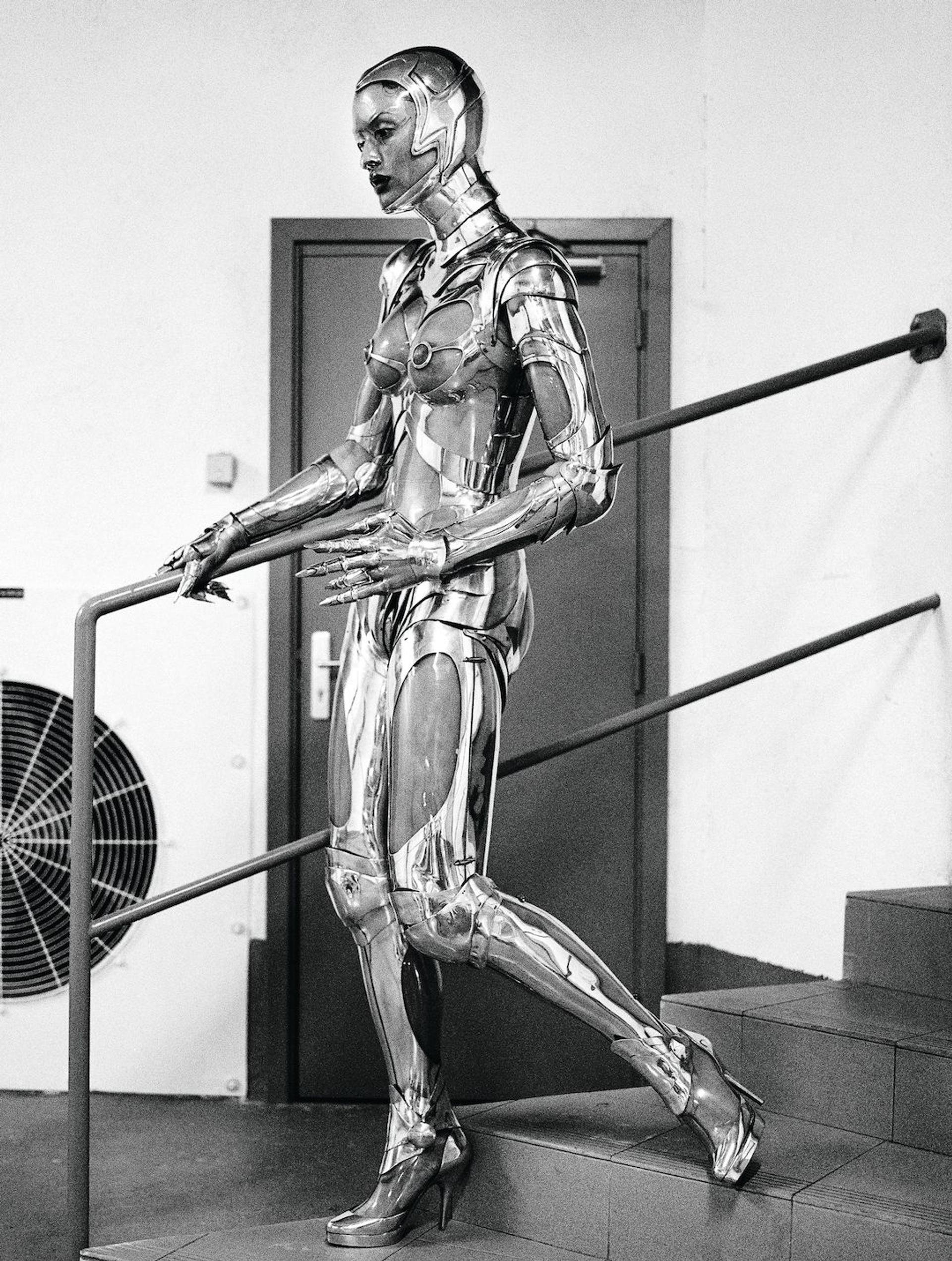

Produced and premiered by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts in March 2019, Thierry Mugler: Couturissime was the first retrospective of the designer’s work, conceived as an opera in five acts. The exhibition assembled 140 Mugler outfits created between 1973 and 2001 – most of which have never been displayed before – and cast them as stars in an immersive performance of costumery, video footage, archival materials, sketches, and images by the crème de la fashion photography. The catalog accompanying this Gesamtkunstwerk is also the first reference monograph devoted to Mugler, and is as spectacular as his défilés were known to be. Fetishism and futurity, tragedy, metamorphosis, and machines – especially femme bots – are explored via Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdin, countless mega-muses (Linda Evangelista, Jerry Hall), icons (Madonna, Beyoncé, Bowie), and the Cirque du Soleil.

Mugler’s work emerges from this “fashion extravaganza” as a dance of seduction: he designed the black floor-length dress worn by Demi Moore in Indecent Proposal (1993), where it incarnates a forbidden desire for possessions and to be possessed. He directed and created the wardrobe for George Michael’s supermodel-studded “Too Funky” music video, with its Anne Bancroft voiceover from The Graduate (1967): “Would you like me to seduce you? Is that what you’re trying to tell me?” Mugler’s eroticism is at once aggressive and accessible, as though his futurist wet dream – of cyborgs and body modification, of industrialized pleasure couture, of armed sex pirates from space – is somehow shared among us, programmed into the early 21st century libido.

When Jack Lang, minister of culture under François Mitterand and a contributor to the Couturissime catalog, appeared at the National Assembly in 1985 in a Thierry Mugler suit – a Mao collar, where ties are mandatory – he made an indelible statement of support for France’s fashion industry. “Le prêt-à-porter est le prêt-à-vivre” President Mitterand declared at a Mugler-organized reception for his fellow French designers: ready-to-wear is ready-to-live. Mugler, in other words, seduced a nation and stimulated an industry capital, a cornerstone of the swollen edifice that is Paris Fashion Week.

Mugler told art historian Linda Nochlin that “fashion is the only art that walks down the street.” Through fashion, he’s said elsewhere, “you create forms of life, the pleasure of being, of coming and going.” Mugler describes a kind of living exoskeleton, animated and fed by and fused with the wearer – at once transhuman and hyper-human, driven not by technology or its aesthetic but with the enhancement of our natural form by any means. If his vision appears to ask a lot of the modern physique, Mugler has used his own body as a canvas as well: in the last decade or so he’s rebuilt his svelte frame, assuming a beefy, pierced and tattooed persona who goes not by Thierry, but by Manfred. “Body sculpting,” he says, “is a journey to the furthest limit of your capacities.”

Yesmin Le Bon wearing Thierry Mugler photographed at the London Palladium for ES Magazine