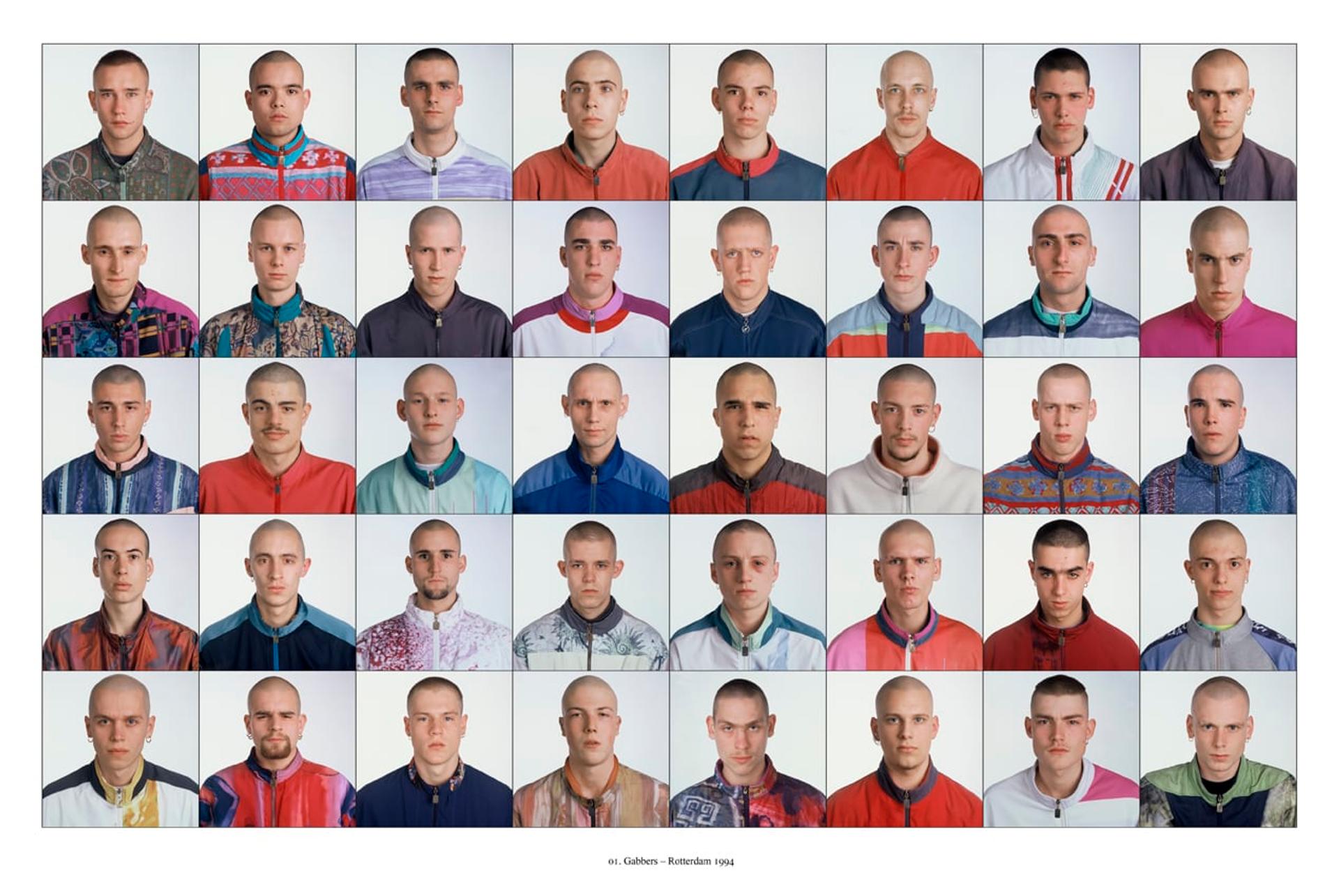

The 154 Exactitudes of Ari Versluis and Ellie Uyttenbroek

Since its first iteration in 1994, Dutch photographer Ari Versluis and “profiler” Ellie Uyttenbroek have been developing their portrait series Exactitudes – a project that sits somewhere between street style blog and sociological study – questioning the nature of individualism and collectivity. Willing participants are photographed and arranged on 3×4 grids in identical poses that allow the nuances that characterize their looks to crystallize.

Exactitudes began with the tempo-switch of Detroit house into gabber in the pair’s hometown, the port city of Rotterdam. Gabber was a semi-isolated, early-internet cultural moment centered around hardcore dance music, Italian tracksuits, shaven heads, and ecstasy. Versluis and Uyttenbroek, art school graduates who had spent time following fashion trends in 1980s London, were uniquely poised to document this subcultural explosion. In the years that followed, they began working in cities including Paris, Casablanca, Beijing, and Rio de Janeiro, publishing the first edition of Exactitudes in book form in 2002 – an anthropological update of August Sander’s People of the 20th Century that has now been reissued six times. There are 154 grids in the 2014 edition, all of which are available to view online (that’s a total of 1,386 street-cast and studio-shot portraits, with a few extras thrown in). Each is accompanied by an audio file in which a man with a cut-glass British accent reads a short, poem-like text, assembled from interviews held with each subject about their lives. The 50th entry, for example, is “Ecopunks,” shot in Rotterdam in 2002: “Tribal anti-consumerists, no-logo-ists. Crossing borders in vans in search of illegal technological enclaves where the music is pumping. No clock, no need, just dogs and magic mushrooms.”

In an age when the big vacuum of targeted marketing sucks up every sound, trend, or movement before it has had the chance to mature, Exactitudes provides a handy timeline for thinking about identity and belonging. Do individual group members find their individuality when they become a “Casual Queer,” “Ghetto Fab,” or “Hashdag,” or do they lose it? How are “social teams” governed? How conscious are members of the codes and associations that their broader group implies, and how has signaling evolved to keep pace with globalization and the brutal omniscience of the internet? (On that point, Versluis has argued that today we dress with silhouettes in mind, the most immediate, visible element of one’s look as realized on a two-dimensional feed.) How do identity politics complicate our understanding of these almost robotically realized groups, and are these rebellious subcultures, or key demographics?

Versluis and Uyttenbroek estimate that a fifth of people belong to what they consider an “exact-attitude,” with the rest being an imperceptible combination of cultural indicators, or maybe context-dependent social chameleons. In the 1990s – the era of Adbusters, independent record labels, and a Boomerish obsession with not “selling out” – people resented being boxed in, cataloged, defined.

Yet through the 2010s, signaling membership of a group, or at least alliance with a set of political beliefs, began to feel like a progressive necessity. Exactitudes claims to not categorize people according to socio-political or cultural specifications, but rather according to style, though sometimes the two align – as in “12. Allahs Girls” in Rotterdam or “143. Annazaranina” in St Petersburg. In this universe, it’s possible for distinctions of race, class, sex, and gender to be usurped by whimsical categorizations like “Omen,” “Meuf,” and “Violet Virus.” It’s a fashion-first lens on society that designer Demna Gvasalia used to frame Vetements’ AW 17 presentation in early 2017. A diverse selection of young and old models, one of whom was street-cast the evening prior to the show, inhabited a range of Parisian stereotypes – the wealthy fur lady, the chic Parisienne, and the rained-on tourist – as well as global subcultural types such as the emo, punk, and gabber, with Exactitudes-style texts for each.

There’s another history interwoven with the Exactitudes story. In January 2018, Helmut Lang announced its Re-Edition Collection with a nine-part grid titled “Helmut Lang Fans, New York, 2018.” Kanye and Solange were among the participants. In 2011, the coffee firm Lavazza commissioned Exactitudes studies along the intersection of fashion and coffee-consumption in Milan, research which added “Team Doppio,” “Americanos,” and “Donna Decaffeinata” to the series. Things change. Partnerships and collaborations are often a pre-condition of cultural production today, and an eye capable of detecting a clothing trend is arguably more valuable from an industry perspective than knowing how to use a camera. Versluis’ work on Exactitudes has always sat parallel to his fashion photography, a selection of which will be on show this Friday December 7 at Space_31 in Berlin. Katja Horvat spoke to Versluis about the history, methods, and findings of the Exactitudes project, 24 years in.

Katja Horvat: The root of Exactitudes lies in fashion. What do you think is the greatest impact fashion has had on society?

Ari Versluis: Fashion is one of the most polluting industries in the world. It’s also the largest stage from which to observe social and cultural change.

Your first investigation explored the identity around Gabber after you were asked to make portraits for a Dutch telecom company about youth culture. Why Gabber?

Post-Punk Rotterdam – which had the biggest port in the world at that time – was the perfect place for the birth of Gabber. It was working-class style revolting against the Dutch house scene in fashionable Amsterdam. There was no escape: the city was simply overwhelmed by those bold hardcore lads in candy-colored tracksuits. Nobody from the world of fashion or art took any notice of the phenomenon in the very early nineties. They were frightened by its alleged nationalistic and racist connotations. It was simply too hardcore. Everything happened on the fringe – in alienated harbor warehouses. No one from the world of high culture made the effort to step into this subcultural world of pills and crazy BPMs. Ellie and I saw the potential straight away.

What kind of potential?

Gabber was “exact-attitudes” pur-sang – uniformed identity to the max. The fashion element of this youth culture intrigued us massively. Not really knowing what to think of it, we started to research the movement by taking pictures of the boys. We invited the right prototypes to come to our studio to get their portrait taken, and noticed the virtue in sameness.

In recent years, Gabber culture has become popular again, and many young designers have looked back for inspiration. How did you feel seeing the culture rise again?

In the mid-nineties, when the scene mellowed down to happy hardcore, art and fashion began to take notice. Suddenly videotapes of the infamous parties and DIY gabber mixtapes were everywhere. The original parties were copied on a large scale. It became a real Dutch youth culture. But a lot of that history exists as anecdote only, and there is actually very little footage or photography from that time that really matters. It was too early for the revolutionary handycams and pocket cameras that came after. Above all, the scene was totally non-narcissistic. They were too much in the moment to even consider documenting it. You can state that the clean looks are still appealing and liberating today: the gabber bitches’ shaven necks; trackies combined with a bra. It’s the aggressive look of Disney in hell.

That makes me think about the Soviets. Nikita Khrushchev was denied permission to visit Disneyland while on a state visit to the United States in 1959. I mention this because the Russian techno scene rose to prominence at the same time as the Dutch, and both scenes are, in a way, very politically driven. Were you ever interested in capturing two similar cultures at the same time?

No. The power of the early series of Exactitudes was that we really concentrated on the world that surrounded us. “Camping,” as we used to call it. Looking at our grannies from a fashion perspective, for instance, was cool enough for us.

How much time do you spend in the research phase looking for people, as opposed to time spent in the studio when the search is over?

Each series is made according to a set timeframe of 3 to 4 weeks, and is most of the time quite site-specific. We love the Hollywood adage “time puts pressure on every scene.” Since observation and encountering people can be such an intense process, you have to limit yourself. We take time after the shoot for composing, analysis, and reflection.

Your second project, “Casual Queers,” was LGBT-oriented, as your studio was located next to a gay bar, right? What role do you think sex and sexuality plays in fashion, or the culture of dressing?

The culture of dressing is characterized not by what you wear, but where and how you wear it. Awareness of one’s environment is crucial. You have to choose your battlefield. Subcultural fashion codes in the domain of sexuality are not easy to read and change constantly. The amount of skin you show has become political again. The gay bar next to our studio was striking at the time for its masculinity in drag. The fact that the guests looked like the ideal son-in-laws told a perfect queer story.

Do you think fashion relates to our sense of identity and who we really are?

Show me your friends and I will tell you who you are. That notion might be more relevant than the story of an individual’s style. It’s the context that does the talking.

Many designers, stylists, and photographers are keen to use fashion as a platform for a sort of “silent” protest – a visual tool to get their message to the wider public. Do you think people with a platform such as yours have a responsibility to the public?

We have no political agenda. We love to collect. Our methodology was criticized for framing people at the start of the project, now we are praised for showing diversity.

When did the switch happen? When did you first start noticing that people are seeing a bigger picture?

When the internet became mainstream.

How do you think the political zeitgeist influences fashion?

Debates around diversity, inclusivity, sustainability, nationalism, migration and gender are all mirrored in contemporary fashion. It is often said that fashion no longer belongs to the avant-garde. This is debatable, but it’s manifestly clear that fashion need to do some soul-searching if it is to move forward in a more progressive way. Algorithms and data that predict fashion trends are now being turned into strategic weapons. The question is: what is the political role of the individual in all of this?

In a column for Spike magazine, Jack Self wrote: “An immense anxiety surrounding fashion seems to prevent everyone but a handful of critics from speaking with any clarity. To my mind, this has a lot to do with the lack of clear propositions by contemporary fashion itself.” Would you agree?

Fashion nowadays is mainstream pop culture. Great! It’s not about designers or labels or the thin theories that surround them, but about the people who wear it and who add that extra wanted or unwanted value. “Who is your real audience?” is a question a lot of fashion houses and labels don’t dare to ask anymore. They’re afraid of cracking the mirror. However, an honest answer could provide them with fresh perspectives and better insights. Shameless reflection is needed to push fashion beyond the neoliberal myths our time. A time that is undoubtedly demanding more diversity and equal representations, and not only at New York Fashion Week.

How has globalization and social media changed our perception of fashion?

We are constantly changing and adjusting the identities we build for ourselves, far more than before the age of social media when the real cool kids were exceptionally tribal and less nervous. Fast fashion, which was presented as a democratization of style in the beginning, results in mindless consumption now. “No past dogmas, endless play . . .”

Do you think fashion needs to be ethical?

Of course. You can’t shine when you know you hurt people, animals or the environment.

Is fashion an art form?

Fashion is fashion. Is art higher in the rankings?

You tell me . . .

Fashion belongs to the domain of design, and design can be a catalyst for change, for better or worse.

And what about the actual experience of encountering “exact-attitudes” on the street? How much do you experience whichever cultural phenomenon you’re working on?

Real is what you feel. You can’t empathize or connect with your participants without experiencing it as well. In the early days, we adapted to the subcultures we were investigating, which made it harder to mingle with other research groups. For instance, we were both bold in the gabber production period – not really appropriate for shooting millionaires at antique fairs. Now we’re fashion chameleons so that we can work on more series.

What are some subcultures that spark your interest most these days?

Common people.

Who is a common person?

We don’t know, really. Social changes are a fact, that’s why we research, stage, and document the casualization of celebrity styles, sporty hijabs, age-agnostic artists. It’s a fabulous time.