The Pendulum: DENNIS FREEDMAN

DENNIS FREEDMAN swings between the worlds of fashion and art. His transition as creative director at W magazine to Barneys New York symbolizes the new magic formula of media, retail, and the spectacle.

The sky behind Dennis Freedman turned dusk purple as he stood in the Long Island City studios of Barneys New York and watched the Italians film the woman with three legs. On the table beside him, a pile of tchotchkes sprawled like the spoils of a police raid at a clown’s house: googly eyes, sparklers, donuts, a paintbrush with blonde hair instead of bristles. These are all items Freedman purchased for the Italians to inspire them.

“This is what I love more than anything,” he whispered, as five of them scurried around him. “What we’re doing right now? The obsessiveness of getting it right? It kinda gives me goosebumps.” Freedman, 61, has a very specific taste that’s impossible to anticipate, a bit like Alan Alda in Woody Allen’s Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989). (“If it bends, it’s funny. If it breaks, it’s not funny.”) The three-legged woman – actually two, sitting side by side – would appear in a surreal video installation for Barneys’ five street-side windows on Madison Avenue. Like the store, the windows are a New York institution, and their decoration every four to six weeks York institution, and their decoration every four to six weeks is Freedman’s most high-profile duty as the company’s creative director.

Freedman isn’t tall, or especially bossy, and his salt and pepper hair was the only thing about him that may have indicated he was in charge of the crew at the studio. For the creative director of one of the world’s hippest and most expensive stores, he doesn’t dress particularly well. Older sweaters with blonde dog hair on them are not uncommon. At W magazine, where he worked for 25 years, he was famous for doing things like uncapping a Sharpie and then plunking down his arm on it. When asked if Freedman dresses well, the photographer Juergen Teller said, “Sometimes.”

Someone slid a copy of The Andy Warhol Diaries under the two models’ butts to fix a height problem and Freedman considered toe angle. An Italian with pierced tragi stood near the tripod and clapped his hands to help them nail the timing the tripod and clapped his hands to help them nail the timing on a triple leg cross. Freedman said little but there was no doubt who was in charge. Under his creative direction, W became if not an anti-Vogue then a punky little sister, a place where photographers like Teller, Bruce Weber, Mario Sorrenti, David Sims, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, and Craig McDean could get weirder and tell more of a story.

Freedman wouldn’t just assign these stories, he’d travel the world with the photographers to help shape them. He was there for the big picture, to lay developed film on tree stumps in Havana to plan the layout, to realize that Eudora Welty lived in Mississippi and – since he was there with Weber anyway – look her up, and shoot her.He never paid any of his photographers more than $2,000 a day, and put his entire budget into the shoot, which yielded spreads that made careers. In 2011 he joined Barneys. made careers.

“I see the DNA of the jobs as not so dissimilar,” Freedman said. “With both you’re selling something and you’ve also got to be hip and creative.” The years since he came to the job have been difficult times for magazines. Declining circulation and, arguably, relevance have led commercial ventures to poach talent from the venerable glossies. Lucy Yeomans, formerly editor-in-chief of British Harper’s Bazaar, is now the editor-in-chief of shopping site Net-a-Porter (its men’s site Mr. Porter having already snatched up former British Esquire editor Jeremy Langmead). In New York, the online deal powerhouse Gilt Groupe hired Ruth Reichl, the former editor of the now defunct Gourmet, former tabloid reporter Ben Widdicombe, and Tyler Thoreson, of mens.style.com. This is all about branding: a word that was always vague but has now been further confused by the evolution of media consumption. Most prominent shopping sites now feature some kind of content that might be described as editorial: interviews, blog posts, the sort of fare you might find in lower-quality magazines, but no worse than that. It works the other way too, the standout winner in that category being Monocle, which sells high-end goods through its website and pop-up stores.

In many ways it’s liberating. If ad placement at magazines has tried to balance clients against suitable stories, the breakdown of the wall completely ends a relationship that was a little schizophrenic, even if it was necessary to preserve editorial integrity.

The word for what Dennis Freedman does now is not advertising. He also directs the company’s mailers (dressed-up catalogues, essentially) and has pioneered a new kind of mailer: the video you can shop. It looks like a music video but when you pause it you can buy everything the young men in it are wearing. It’s the sort of thing you can do with unlimited resources. Dennis showed me the latest one on an iPad in a car riding to the Barneys studios. Immediately after, he called a Barneys honcho about it. “This is so great,” he said. “It should be on Taxi TV, is where it should be.”

The Italians in the studio, who circled Freedman, came as the crew of Yuri Ancarani, an Italian video artist who watched everything from a stool and was recommended by Maurizio Cattelan, whose magazine Toilet Paper came out of his work with W. The windows that would be installed in two weeks would be deeply surreal: televisions on conveyer belts, pendulums, electropop music. They’re based in part on the Rube Goldberg-esque Fischli/Weiss video The Way Things Go (1987). Yuri’s videos would take center stage in the windows, the theme of which was “Neo Modern,” which Freedman said, “doesn’t mean – well, it’s vague.” (It seems to have roots in postmodern furniture.) He liked the aesthetic of it and didn’t underrate the name. In naming something, he said, you “create a world.” This one was about the “cycle of buying and selling.”

While at W, Freedman started the magazine’s art issue, which would do things like invite John Baldessari, Roni Horn, and Matthew Barney to collaborate on the shoots. He had Richard Prince, Lisa Yuskavage, and Tom Sachs offer their takes on Kate Moss, and had Richard Tuttle build a set for Mario Sorrenti. He’s taken this idea of blending art and fashion with him to Barneys. One effort last year, a partnership with Dakis Joannou’s Deste Fashion Collection displayed artworks inspired by fashion but, as a New York shopping blog reported in an awed headline, “There’s Absolutely No Merch on Display at Barneys this Month.” Teller contributed a huge anti-window, a wooden outcropping where the window should be with a hideous photograph of Yves Saint Laurent on it, and at the opening party the artist John Bock cut up clothing, sewed it into new clothing, and presented it to attendees. “Oh my God,” Freedman said at the party, when someone presented him with a pair of suit pants that had been modified with socks and a bra on the seat. “Holy shit. Oh my god. I don’t know if these are going to fit, but, you know what? If they don’t, I’m going to lose weight.”

The initial proposals for the videos were overly goofy, Freedman felt. Yuri wanted to do something with someone in a monkey suit, bouncing up and down on a pogo stick. This was why Dennis gave the Italians the Barneys credit card and told them to go nuts, buy a bunch of junk in Chinatown. Subsequent proposals were more absurd and, in Freedman’s view, much better. He reviewed them in the studio. There was a man popping his own head like a balloon and a half eaten banana floating through space. In the studio he mentioned that he also wanted “something on a pendulum” swinging in one of the windows. “We’re not sure what it is yet,” he added. “Might be a pickle.”

You get the sense that his attention span also tends to swing back and forth freely. He’ll wander into another room while someone’s talking to him and leave his jacket elsewhere. When Goodfellas (1990) hit theaters, Freedman did a feature for W on Martin Scorsese’s mother and she gave him her recipe for pasta, her pasta, the pasta she serves Joe Pesci, Robert De Niro, and Ray Liotta in the famous scene of that movie. He lost the recipe.

“I don’t know how many shoots I’ve been on where he’s lost his phone,” Juergen Teller said. According to Teller, Freedman also has a penchant for disappearing into furniture shops while on shoots in, say, Mexico. “He may be in there for a half an hour, which is a hell of a fucking long time on a shoot!” Teller said. “You have 13 people saying, ‘Where the fuck is Dennis?’” So the props are important for structure. If you thought about it in a macro way, the videos themselves were props, since Freedman didn’t know exactly how they’d go in the windows yet, and the people he’d hired to make them, also, were props. He didn’t really know how any of this was going to come together. This was the ideas period.

Dennis Freedman grew up in the 50s, in a middle-class Jewish family in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and eventually went to Penn State University, where he studied studio art. The bulk of his work, funnily enough, was installations. One crowning achievement was a messy bed piece – way before Tracey Emin – placed in the lobby of the art school. It belonged to his roommate, and his roommate’s girlfriend, whom he frequently heard having sex. He asked them to record one of their sessions and hid a tape player under the pillow. The sounds greeted everyone walking to class.

When something isn’t just right, you get the feeling that what annoys Freedman most is that he isn’t as impressed as he could be. He likes to be impressed. When he’s impressed he booms, in his deep voice, “WOOOW” or “Are you kidding me?” or “That’s amaaaaaaaaaaaaazing.” Sometimes he goes high, as when he was impressed at how similar the two three-legged women’s jeans were.

“‘They’re the exact same pant!’” he beamed.

“‘Yeah,’” said Tommy, one of his assistants, “‘We bought them at this store called Barneys?’”

One of his favorite Barneys war stories involves a particular window with a post-apocalyptic scene that featured a tiny robotic cockroach that jumped every few seconds. Dennis didn’t like how it jumped. He worked in the windows with his assistants until two a.m. to perfect the jumping. Ultimately he was never pleased with it, but at least he got an object-lesson out of it: Dennis Freedman cares about the smallest, ugliest detail in the window of a billion dollar store where the average price of shoes is $770, according to Women’s Wear Daily.

In rapid succession the team decided to spell out the words Neo Modern, using stop-motion, on some part of the model. Her forehead, someone suggested, no, her tongue. Shoot her standing up against the green screen. But what if she moved her head slightly? They decided to lay down a reflective blue sheet and have her lie on the ground. The Italians positioned the tripod over her body and zoomed in on her mouth. “Your mouth is just beaaaautiful,” Freedman told her, and it was. It looked very wet and red. The studio assistant – who’d previously been her third leg – placed the letters on her tongue. Each take had her bring the letter inside of her mouth, then the cameras rolled, and it emerged. They’d been shooting since early in the morning, and now outside it was night. As everyone stood over her, the tripod on her chest, the model asked what time it was and then asked if anyone had called a car for her.

Barneys didn’t pioneer window design, but they’ve always done them the best, partly because of the unique way the store has reflected the city itself. Founded in 1923 by Barney Pressman, Barneys undercut the competition by importing name-brand suits from stores in the South. “For the Man Who Knows,” read the windows of the store’s original location, at 17th and 7th in Chelsea, not far from the door-to-door galleries that now crowd the grid near the Hudson River. It was a winning combination, at least in part because New York is a place where anybody can make it with money, but the impressive thing is to succeed without it.

Womenswear came in the 70s. In the 80s, under Fred Pressman, for whom the top floor restaurant in the current location is named, the store went high-end to suit the new New York. There’s apparently a song in the upcoming “American Psycho” musical set there, “You Are What You Wear.”

Barneys always got the joke. In 1986 they hired Simon Doonan as its first creative director, and his witty windows made them famous. Doonan’s were craftier than Freedman’s, more papier-mâché and definitely kitschier, a “hokey yet lethal mix of punk and camp,” as he puts it in his book Confessions of a Window Dresser (2001). He wasn’t afraid to have a shark built out of designer jeans, or incorporate pop culture figures like Madonna, Nancy Reagan, or Mikhail Gorbachev. He had the essayist David Rakoff play Sigmund Freud one Christmas and dispense advice to passersby. In a more recent live installation, Freedman had beer-heiress and fashion icon Daphne Guinness prepare for the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual fashion gala in his windows. Guinness is a friend and Freedman wanted to highlight her as a part of the city he loves. “New York is a place of tremendous talent and I’m just trying to harness it all,” he said.

Movement and technology are a big part of how Freedman differentiates himself other window dressers. He’s had live fish tanks in the windows and Christian Louboutins that stalk each other in a mechanical circle. Most of his technology work takes place at the Flatbush Avenue studios of James Patten, who has a doctorate from the MIT Media Lab and is TED fellow. At a dinner, Freedman was so enthusiastic when trying to explain the concept of TED to the Italians that one of them leaned in to ask “And this thing, it takes place in the desert, yes?” They thought he’d been talking about Burning Man.

“To me, the windows have three elements,” Freedman said one evening at the store, as workers around him set up the intricate metal structures that would hold the video screens. The thing at the end of the pendulum, they’d decided, would be a white bowling ball with a pupil painted on it. “They’re installation art, they’re theater, and they’re commercial, which is a little weird, when you think about it, that last part. Nine times out of 10 we have to think about what to do with these dresses, which is just weird.”

In 1993 Barneys expanded to its 230,000 square foot flagship space on Madison Avenue between 60th and 61st. This was where the windows entered the public consciousness under Doonan, and where Freedman was overseeing the install. He’d brought his dog Jake – a golden Labrador – and let him off the chain to wander the store’s grand first floor, where they sell mostly jewelry and handbags. It was as surrealistic a sight as anything in the windows. Jake went deeper and deeper into the empty store, reaching the far back jewelry counter and kept looking back at his master, almost as if he was puzzled that the usual grand dames weren’t there.

“What’s up Jake?” said one of the tattooed installers once he’d returned back to the windows. “You going to get a Goyard collar?”

“Oh God, no,” Freedman said. “Someone actually gave him one once and he just couldn’t deal with it. He is not some little French dog.” Jake drifted near to the door and the actress Anna Kendrick – coming down from an event at Fred’s – stooped to pet him on her way out. She told him she thought he’d look good in Prada.

The install team would spend late hours with Freedman on Madison Avenue throughout the next week, standing in the January cold and ducking back inside the store to move something in the windows half an inch. The work also continued through the day. Once, as shoppers went in and out the front doors, two interns crawled into the window to scrape an almost undetectable amount of black paint off the part of the glass at the windows’ base, left over from a Christmas partnership with Disney. Those windows had videos with the company’s signature characters stretched skinny like models (“The standard Minnie Mouse [would] not look so good in a Lanvin dress,” WWD was told at the time.) On the sidewalk, Freedman and his assistant Matt watched the interns go to work on the black paint with razor blades. Matt told his boss that the other day one of them had shown up to work in head to toe Givenchy. Freedman smiled. “The thing about this is that even with this task,” he said, gesturing to the window. “You can tell which one is going to be the one to succeed later. You can tell.”

Coming back from James Patten’s studio one evening, Freedman stopped by the Barneys space in Long Island City to see Bob Racine’s progress. Racine is a hair stylist (many would say he’s more of a hair artist) whose work would feature prominently in the next windows, the ones that would be installed after Neo Modern. This was to be a collaboration with Chloé that would highlight archive material from Karl Lagerfeld’s early work, celebrating 60 years of Chloé. All the mannequins would have outrageous bouffants, which would draw attention to the dresses and squares with Freedman’s general dislike of standard mannequins for their familiarity.

Racine had wrapped up work for the day before he was offered a ride back to Manhattan in the Barneys car. As the car approached the Queensboro Bridge, Freedman mentioned that he’d been rereading The Andy Warhol Diaries. What he loved most about it was Warhol’s pithy voice. Warhol once had to visit Jamie Wyeth out in Pennsylvania and in the book he describes the old women out there as looking like bulldogs. “Can’t you just see it?” Freedman quipped. “In New York, you might have some surgery but out there, it’s just like, ‘bulldogs.’”

Racine, who knew Warhol personally, also thought that was great. It was the brevity of the whole thing, Warhol always had brevity. “You know, Warhol’s the reason I started cutting hair,” he said. Bob Racine was 16, 17, one of the punk wannabe artists who used to hang around him downtown in the 1970s, only interested in motorcycles and his bands. One day, Warhol sent him uptown, something he’d regularly do with those kids, so society could meet the hot young things (these days, they tend to go right to the source: sometimes you’ll see MoMA trustees at even the edgier openings on the Lower East Side).

The young Racine was introduced to Geraldine Stutz, then the president of Henri Bendel, and in turn Jean Louis David, who was about to open his first New York boutique in Henri Bendel. Jean Louis David took a liking to Racine and offered him a trip to Paris to learn hair. Warhol thought he should do it. “I said, ‘Andy,’” Bob said. “‘I’m an artist what do I want with hair?’ And Andy’s response, I’ll never forget was just, ‘Whatever, Bob.’” He raised his voice and put his hands up to mimic Warhol, like “your loss.” Brevity.

Of course Racine went to Paris and loved it. Hair was just a new material for him, like motorcycle parts. He was a prodigy. “I go back to New York after three years of working for Jean Louis and I bump into Warhol. The first thing he says to me?” Racine raised his voice again. “‘Oh. Look. The artist is back.’ Like ‘told you so.’”

Freedman also stumbled into the things that he loved. After college he was rejected from the Slade School of Art in London, and instead studied environmental design at Parson’s School of Design in New York. He spent three years as an interior decorator, and sampled all he could of the New York that was: bars, dancing, Studio 54. He’d generally return home by one a.m. to eat a pint of ice cream and watch back-to-back reruns of the Mary Tyler Moore Show. (You may remember its opening, with the slow motion hat throw and “You’re going to make it after alllll!”) He quit interior design because he wanted more from his job.

Because he knew typography and design, a dentist friend of his had him design a pamphlet for his practice. Freedman thought he might be able to make a job of it and the dentist friend introduced him to Charles Churchward, then the designer of House & Garden magazine and a patient. On Churchward’s advice Freedman took magazine design classes at the School of Visual Arts, once cutting up a first edition of William Eggleston’s Guide (1976) for a project, and in the early 1980s began to do freelance design work for M magazine. From there he was made features editor of W by its founder John Fairchild – a New York character in his own right – who until recently wrote a gossip column in W under the pseudonym Countess Louise J. Esterhazy. Everyone who ever worked for him still calls him “Mr. Fairchild.”

“Mr. Fairchild saw something in me,” Freedman recalled. “He used to take me to lunch at the Four Seasons all the time, and La Grenouille. I remember I was wearing Salvation Army clothes, like five jackets for 25 dollars.” Founded in 1972, W was initially a spin off of WWD, a bi-monthly broadsheet focused more on society and gossip to WWD’s industry coverage. In 1993 they decided to go glossy and monthly. Freedman, then in his early 40s, and the design director Edward Leida talked about how to go about the transition in Friday night car rides to their homes on Long Island. It was freewheeling, and a great success. “Corporate America is not such a big deal as long as you do not take it too seriously,” Doonan wrote in Confessions.

Freedman’s boss, the editor Patrick McCarthy, gave him leeway. McCarthy, who oversaw the introduction of W as purely a fashion magazine, only ever killed three photo spreads during his time there: once, Freedman sent the painter Karen Kilimnik to cover fashion week and she turned in drawings inspired by the Kirov ballet, complete with horses. Too out there. Another killed piece, by Mario Sorrenti, had models in it who had clearly just committed suicide. The last was by Wayne Maser, who turned in something “involving a woman and a dog,” that he didn’t even want to talk about.

“I wouldn’t have done it well if my heart wasn’t in it,” he said. “I’ll never forget there was this one time, when times were tough, that we did, for lack of a better thing, a huge collection story that was very straightforward. We shot 100 dresses and I remember when it came in – I won’t say who the photographer was – I thought, gosh this is really – I don’t know where this story belongs. It just felt out of place, felt like another magazine. And what happened when that story was published at that time? Oh my God, we got flowers. Designers sent flowers.” They were relieved to have something a little blander, a little more normal.

I asked Freedman if the transition to Barneys was difficult, the store being a more commercial place than W. He disagreed that they were different at all. “I always think I try to do what is the right commercial thing,” he said. That, he said, is all he was doing at W, developing a voice that was more interesting artistically, sure, but also more marketable.

“If you’re for everyone you’re for no one”

“Once you lose that voice, you lose something and then in the long term I’m not sure where you are,” he said. “I think that what we built was a very commercial magazine and a very distinct voice in a field of I don’t know how many others. The brand needs to define itself.”

His main job at Barneys was to find that voice for Barneys, he said, and it wouldn’t be for everyone. This was actually consistent with his work at W, where he and Edward Leida used to joke that the tagline for the magazine could be “not for you.”

I said I thought that sounded odd for someone working at a store. Doesn’t Barneys want to be for everyone? Freedman scoffed at the idea. There are Democrats, he said, Republicans. J. Crew isn’t even for everyone. “If you’re for everyone you’re for no one,” he said.

Near the end of the 1990s, Dennis Freedman began his furniture collection, which begins with Italian Radical Design from the 1960s and continues to the work of contemporaries like Dutch designer Joris Laarman. The collection began with a Capitello (1965) chair by Studio 65, a self-skinning polyurethane foam piece whose design is based on an Ionic capital. He bought it from Christie’s for some $5,000, the most anyone had ever paid for a Capitello chair at that time. Now as he travels the world for shoots he always keeps an eye out for rare pieces. He keeps some 100 items from the collection in his vacation home in Long Island, a carriage house that used to serve as the garage of S. Fullerton Weaver, of the architecture firm Schultze and Weaver. Another 200 pieces sit in an off-site warehouse. Some of them have been included in gallery shows, though it’s mostly a personal project.

Condé Nast purchased Fairchild Publications in 1999, and the magazine continued to do well. In 2005 the company moved to 750 3rd Avenue, near the Condé mothership at 4 Times Square, and Dennis helped redesign the cafeteria, which featured pulsating light walls, in collaboration with the architect Roger Duffy and Leo Villareal.

After many years of healthy ad sales the global recession hit W, and many other magazines, hard. Between 2008 and 2009, W lost 46 percent of its ad pages. Freedman left for Barneys, which was not unaffected by the recession itself. In 2007 Istithmar World – Dubai’s sovereign wealth fund – bailed the company out of bankruptcy and in 2012 again had a new owner in Richard Perry, the hedge funder, Pop Art collector, and husband of designer Lisa Perry.

If Freedman’s life in New York has been about balancing his passions – design and art – with practical outlets for them in media and retail, he’s been a man of his time. All four businesses swap resources more frequently than ever. François Pinault has owned Christie’s since 1998, the same year LVMH purchased the auction house then known as Phillips de Pury & Co. Carine Roitfeld’s son, Vladimir, has carved out an identity for himself as an art dealer. Marc Jacobs has collaborated with both Takashi Murakami and Yayoi Kusama. Alexander McQueen’s show at the Met was the museum’s eighth most popular show of all time.

Not everyone is happy with the cocktail. “The growing mania for a mélange of fashion with art is great for the former, but it has been a gravitas-eroding catastrophe for the latter,” wrote Doonan, in a column for Slate denouncing art Basel Miami Beach. “The world of style is ephemeral and superficial by nature. Art, real art, fabulous art, high art, must soar and endure and remain unencumbered by the need to sell handbags and blouses.”

Freedman, of course, has no hand in any of that (for one thing he doesn’t seem to care too terribly much about fashion qua fashion). He can still remember the names of the galleries he visited in New York as a teenager and if he frequently brings on artists for jobs it’s simply because he feels they have the most to offer, in any situation. He thought each artist in the one W art issue understood Kate Moss better than any fashion photographer ever could. You get the sense that if he could have a gallery artist make his lunch every day, he would.

Neo Modern was a huge success. There were worries that the component parts, the spinning television sets, the dresses, and the music – audible from the sidewalk – might be slightly overwhelming because he’d poured so much into each element, but in the end they grabbed you and wouldn’t let you look away. The videos were chaotic but the structures in which they moved, the giant wheels and conveyor belts, seemed to suggest a controlled creative logic, the kind that probably went into the designing of such dresses. And nothing drew people in like the eyeball pendulum, which tick-tocked before a video camera that would cut into the feed to show the people on the street the new surrealistic video that was being made right before them. However, they were not in the video. The camera faced the back.

There was really only one hiccup in that the police had to ask the store to turn the music down.

“I think Barneys is a very fortunate continuation of everything that I care about creatively,” Freedman said. The main difference, he pointed out, is that now he’s working in three-dimensions.

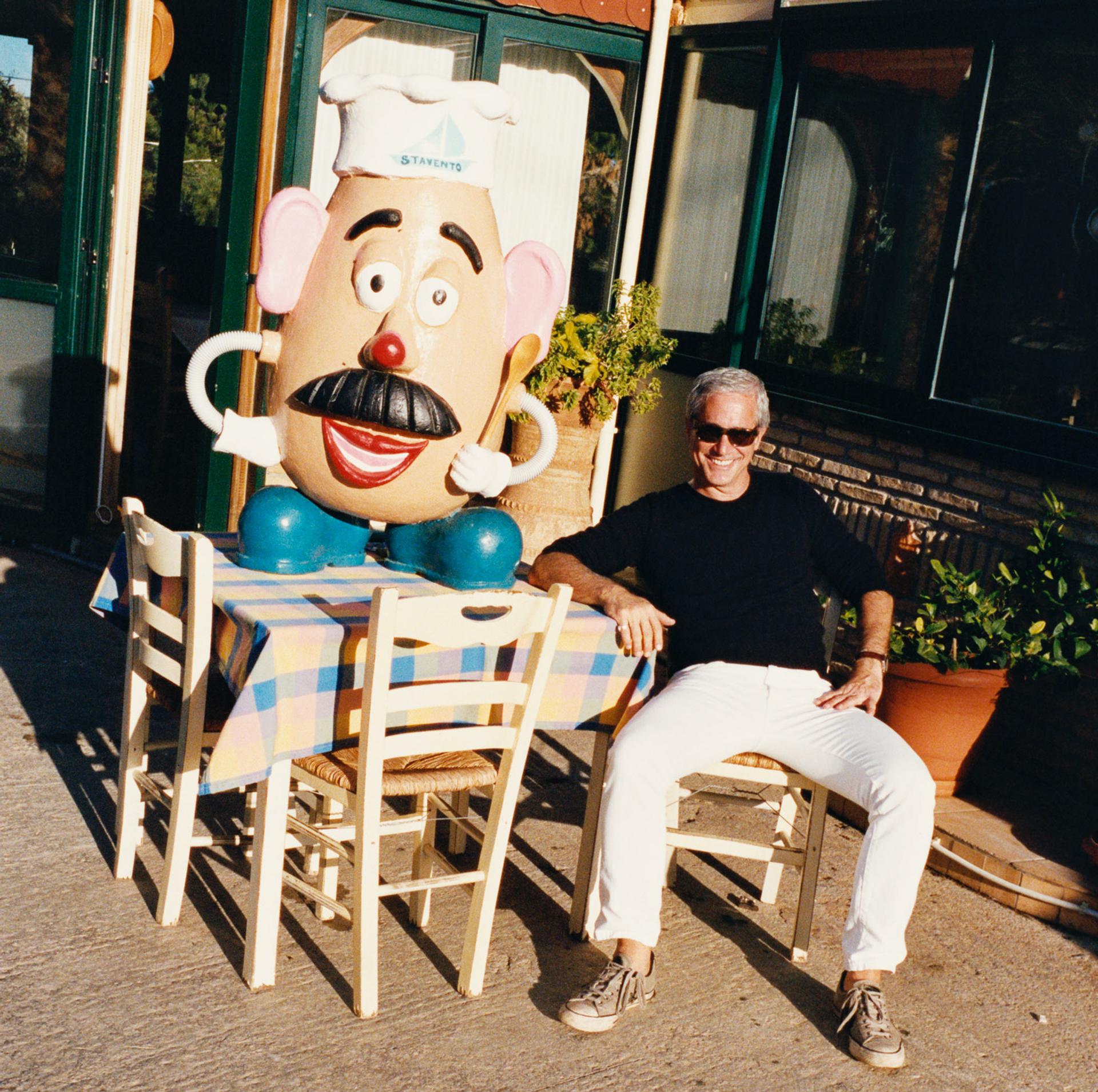

By DAN DURAY, Portraits JUERGEN TELLER