Going Over: The Social Dimensions of Men’s Hairstyling in Kuwait and Beyond

Last year, an Iranian cleric claimed women who wear revealing clothes cause natural disasters. Hojjat ol-eslam Kazem Sediqi, a prayer leader in Tehran, made the ludicrous statement that “many men who do not groom their hair modestly lead young women astray and spread adultery in society, which increases earthquakes.”

Surveying the spectrum of manly barbershop possibilities, Kuwait

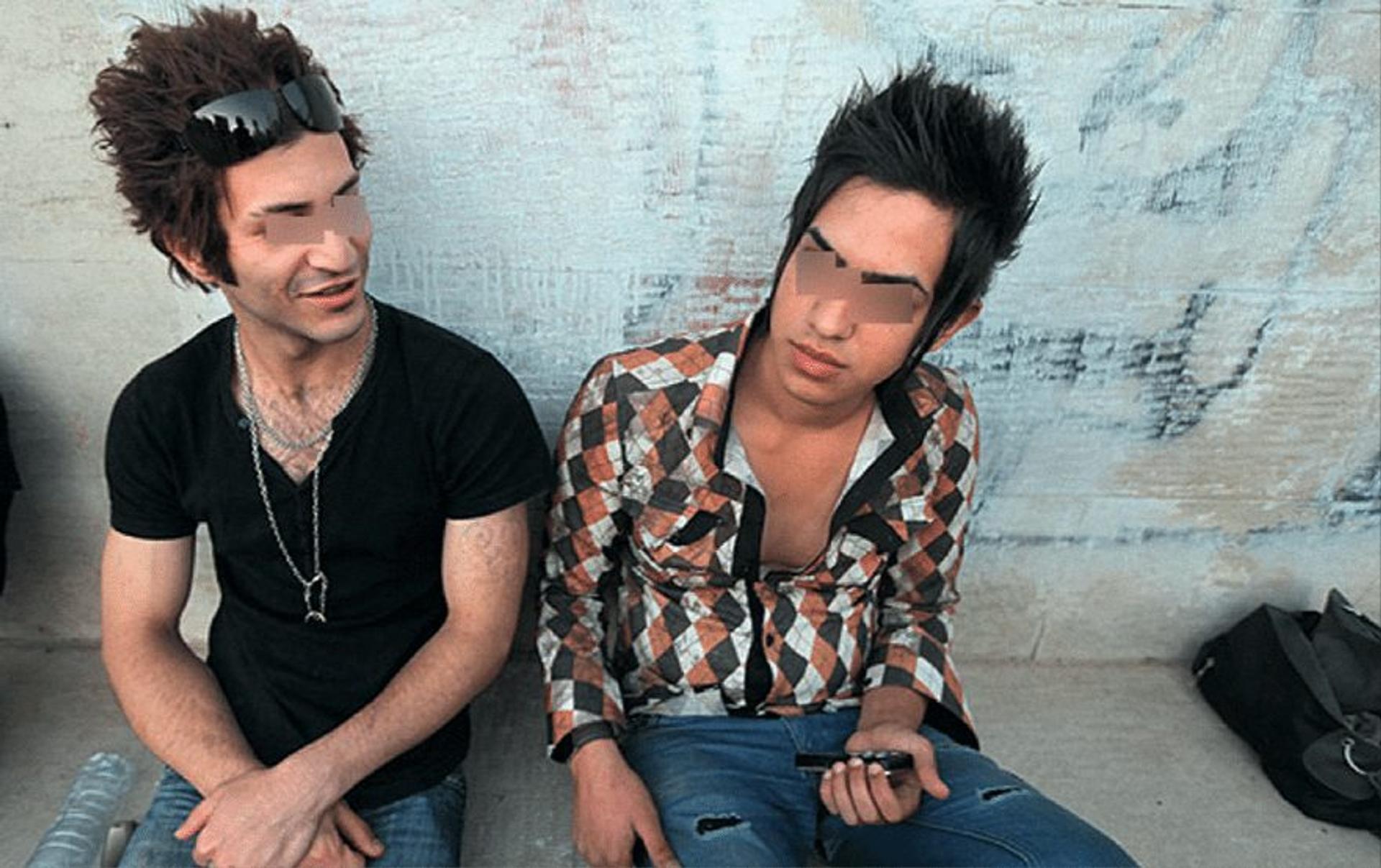

Lethally styled: Kuwait City Youth

It is without a doubt that hair in this region is a fixation – an obsession, even. Culturally and religiously, some women were, and still are, mandated to cover it, while their male counterparts combed, teased, curled, straightened, dyed, and transmogrified the hair on their heads and faces. Wealthy Sumerian men wore helmets of gold that mimicked the popular hairdos of the day, elevating a fleeting distraction to an eternal monumentality – an act that recalls the love affair between the Middle Eastern man and his hair. It is also common knowledge that the predominant religion of this region, Islam, concerns itself with the minutiæ of its followers’ lives. Outlines and restrictions on such worldly matters as business transactions are codified in a spiritual context in a way that is evocative of wider regional predilections.

One such seemingly frivolous aspect of a believer’s life that has not been left unaddressed by the divine is hygiene. In this case, grooming and hair care. The Islamic concept of fitra – human, innate, civilized disposition – and its physical manifestation – the fitra of the human body – helps shed light on Islam’s recontextualization of the seemingly earthbound and vainglorious into the profound. Aisha, the wife of the prophet Mohammed, quoted her husband saying, “Ten are the acts according to fitra: clipping the mustache, letting the beard grow, using the tooth-stick, snuffing water in the nose, cutting the nails, washing the finger joints, plucking the hair under the armpits, shaving the pubic hair, and cleaning one’s private parts with water. The narrator said: I have forgotten the tenth, but it may have been rinsing the mouth.”

Despite popular misconceptions, this fixation goes beyond Islam. Other regional cultures predated Islam and concerned themselves equally with hairdos. Women – especially aristocratic ones – in Assyria, Babylonia, Persia, and Pre-Islamic Arabia all wore veils to cover their hair, while their brothers and husbands indulged themselves with elaborate beards and fancy coifs, using oils and curling irons to achieve a cultural ideal. So despite Islam codifying these sentiments in relatively contemporary times, the region’s obsession with hair is undeniably innate and is a pillar of its identity throughout history.

The seemingly oxymoronic notion of the adorned man is, in a way, tautological when placed within the context of this region. In Islam, the image of a groomed, manscaped man – according to the rules of fitra – connotes piety and religious fervor; ideal husband-material for interested parties. While in the classical, pre-Islamic civilizations of the region, the adorned man sends the message: I am affluent, I am cultured and fashionable. A man with an updo, a fanciful beard, or a clipped mustache is a man to be desired, a virile man.

In antiquity, erect hair was the domain of grown men, soldiers, and government officials, while its modern incarnation is the domain of the idle youth. Tall hair that looks like it’s frozen in perpetual motion is the current trend. Its origins can be traced to David Beckham, Cristiano Ronaldo, Lionel Messi, and the countless other football players that the youth adore. This style of hair embodies not only the eccentric haircuts of the players, but the movement and action of a football player’s hair in mid-jump.

Football, the de facto “world sport,” creates an apolitical and secular public space that allows people to release the emotions, anger, and frustration created by a culture of conformity and strict social formalities. In football, there’s a dichotomy between regimented discipline and rebellious freedom. The strict diets, rules, and regulations that are part of a football player’s performance regimen mean that their lives are, for periods, under strict control. Their uniforms, representing a collective whole, present a unified façade. And so, their expressive playing style and their distinctive hair is the only thing that sets one player apart from another.

In July 2010, in an attempt to rid the country of “decadent Western culture,” Iran’s culture ministry produced a catalogue of haircuts that meet government approval. This was the first regulation for men’s hairstyles since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. On the banned list were ponytails, spikes, mullets, and mohawks. Although most of the acceptable styles were in the Simon Cowell genre, the BBC noted that “the featured haircuts weren’t entirely without a sense of whimsy, including a 50s-style pompadour complete with sideburns and a 1990s Hugh Grant floppy mop.” Using hair gel, in modest quantities, is also within the law. Interestingly, none of the models shown in the hairstyle catalogue wore religious beards, perhaps as a way of appealing to younger and less pious Iranian men. The “regulations” have actually been around for ages, but now every barbershop has the government poster pinned up, just for good measure, since barbers rarely follow the rules.

While Kuwait has little to no appearance regulations, there exists the same acute fixation on hair. Emad, a Syrian barber from Papillon, says Kuwaitis basically take trends and “exit them through transformation and exaggeration.” What Emad means by “exiting trends” is when an existing global trend is transmogrified through the filter of local popular media, resulting in a highly localized and specific trend.

More than presenting a masculine ideal, the goal is to stand out, to differentiate oneself in a conforming context. Young men, who tend to loiter and peacock around shopping malls, are taking their hair to new extremes in order to attract the attention of members of the opposite sex. These looks express defiance, while implicating status and independence.

Beckham’s hairstyle, which became known in Kuwait as il-Deech (the Rooster), was the original haircut from which the present styles evolved. From the beginning, Emad’s clients would come in the day after he had cut their Rooster and demand he make it “more.” The young men competed over whose hair was “higher” or had more “electricity.” Another popular haircut is the Quaresma, originally pronounced “Karisma.” It is light, textured and long, and the boys went “over” on it. They exaggerated it to an unrecognizable level. Blending the Beckham, the Karisma, and the “Over” Rooster, the wearers created a new style where the bangs are thin, layered, textured, and swept over, while the top is made high and animated. Where the original hairstyles were easily identifiable and derivative of David Beckham’s iconic fauxhawks, the current styles have evolved in so many directions that none of these styles have names anymore. According to Emad, this trend in hairstyles is broadly called “Over,” as in overdone.

In the same way Beckham and Ronaldo are restricted by their uniforms, the youth of Kuwait and Iran are subjected to the throngs of mainstream, cultural, and religious conformity and regulations. And, despite the commercial intentions of aggressive marketing techniques, these youth use their hair – specifically the “Over” style – as a crucial method of expressing rebellion, individuality and personal growth from boyhood to manhood, from dependence to independence.

By FATIMA AL QADIRI and KHALID AL GHARABALLI