The Trap

The landscape photographs that set the stage for Vincent Desailly’s The Trap betray two distinct worlds. In the first, ethereal golden light cascades through the limbs of towering trees, illuminating a patch of bronze-colored pine needles on a suburban Atlanta street. Six pages in, preceded by a reticent definition of the terms “trap,” “trap house,” and “trap music;” a partial map of Atlanta bleed printed on facing vellum pages, and an excerpt on the origins of Trap music borrowed from The Autobiography of Gucci Mane, Downtown Atlanta’s imposing skyline forms a counterpoint to the book’s initial mise-en-scène. The converging lines of perspective indicated by the freeways that lead in and out of the black metropolis are flanked by bushes that taper from view at the center of the image, where the city springs out of the ground like pillars of refined gemstone. Nature, from this viewpoint, has no place in the city. By contrast, its extensive sprawl – the backdrop for Atlanta’s trap culture that is the subject of the book – is lush, verdant, and overflowing with foliage.

Leafing through The Trap, this greenery takes on its own confining quality. Lurking just out of focus in a large number of the volume’s outdoor portraits is a barrier of trees. Haunting, encircling, they implore us to recall their particular weight in the American South: these are the trees of Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit.” The land of the trap house is also the land of the plantation house, inextricably entwined in economic and geographical legacy.

“The converging lines of perspective indicated by the freeways that lead in and out of the black metropolis are flanked by bushes that taper from view at the center of the image, where the city springs out of the ground like pillars of refined gemstone. Nature, from this viewpoint, has no place in the city. By contrast, its extensive sprawl – the backdrop for Atlanta’s trap culture that is the subject of the book – is lush, verdant, and overflowing with foliage.”

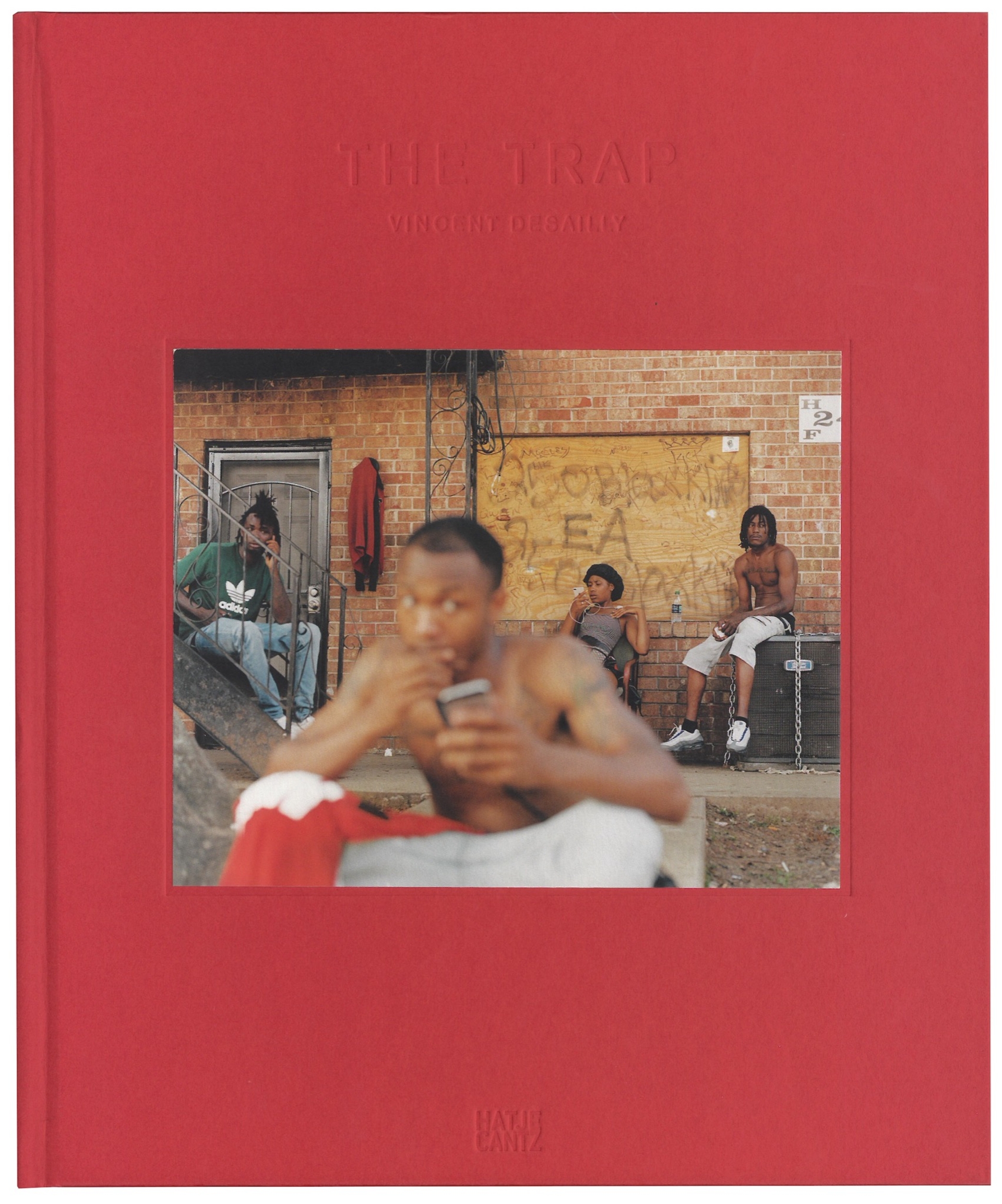

The Trap provides a textured overview of the people, places, and activities that give inspiration to the hip-hop subgenre for which the book is named. Vining out of the Atlanta drug market’s trap houses, the music has grown into a global phenomenon, adopted by artists in neighboring Athens, Georgia, to the far shores of Athens, Greece. Citing this international impact as the reason for his attraction to the subject, Desailly said in an interview with It’s Nice That: “I’ve always wanted to know what it’s like to live in a historical cultural moment from the inside.” But in the shadows of seemingly innocent curiosity is a nagging question about the politics of racial subjectivity, which the photographer seems keen to avoid.

With the exception of the short texts that open the book, there are almost no words in Desailly’s first monograph. In interviews, he makes clear that it was a conscious decision to let the work speak for itself, but the omission of personal reflection begs questions about the French photographer’s qualifications. The viewer receives no context for Desailly’s subjective authority, and the vellum-paper maps that sporadically punctuate the book do little other than reinforce the artist’s birds-eye relationship to the material at hand. The definitions posed at the book’s outset draw a necessary connection between physical ensnarement and the ensnarement of historical circumstance, but presuppose that the viewer is unfamiliar with the terms and culture of the trap, and reinforce the voyeurism of the endeavor.

An artist does not need to belong to a given group in order to depict it, and Desailly’s portraits are taken with apparent sensitivity. But the desolate city and its aloofness to nature, placed in opposition to the verdant overgrowth of a place named for inescapability, presents the trap as an island; a monolith. Desailly’s image of a child in graduation robes, flashing his diploma and a smile, is a rare depiction of joy and levity among photographs of drugs and strippers. Even the ATV meetups of East Atlanta, which are known for the passion and enthusiasm of their participants, are depicted here in melancholy tones. When a white man attempts to narrate the story of black entrepreneurialism, the historical fallacies that for centuries have been perpetrated through this relation of power form a dense woods of skepticism. For this black reviewer, the artist’s good intentions – and enchanting images – are obscured by the trees, the work’s allure but a tempting mirage of sunlight in the distance.