X-RAY AUDIO: The “Bone Music” of the Soviet Union

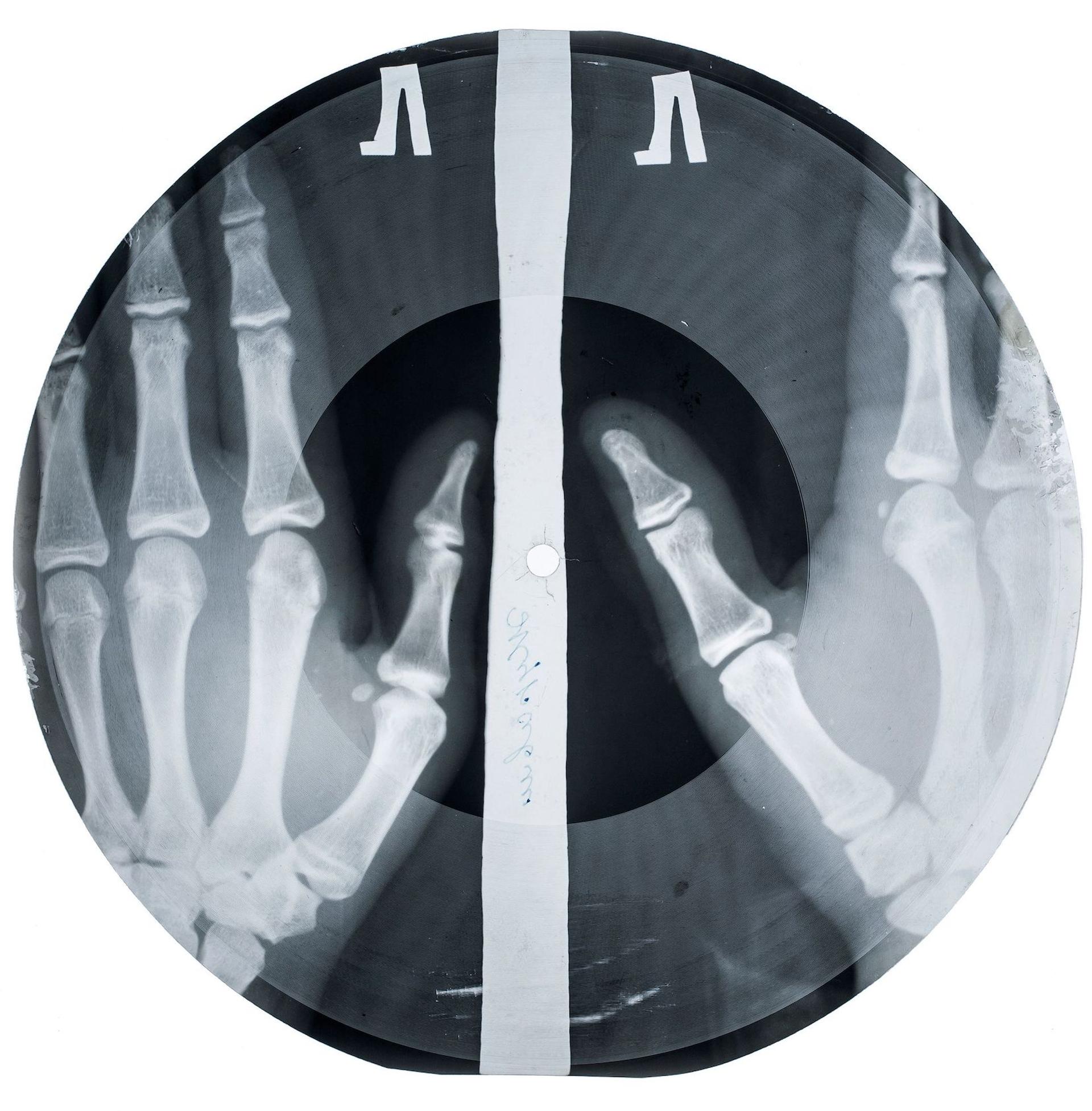

The Soviet Union’s brutal control over the record industry in the mid-20th century led a group of risk-tolerant audiophiles to begin printing and circulating forbidden music on records from the macabre material available to them: x-ray film. Founded in 2016 by Paul Heartfield and my interviewee STEPHEN COATES, the X-Ray Audio project is dedicated to that hidden material archive, uncovering the ligaments connecting those who made and loved these skeleton records. X-Ray Audio’s exhibition “Bone Music” at Berlin’s Villa Heike – located in the former Stasi restricted area – closed this weekend, but a book of the same name will be out later this year on MIT Press.

Vincent Mitchell: I’m curious about how these records were sold. Were people slinging them on street corners? In speakeasies? Within shipments of consumer goods?

Stephen Coates: Well, early on they were sold on street corners and in flea markets. Sellers would hang out in public areas, where dealers today might sell soft drugs like weed. Obviously if you knew a bootlegger you could make an appointment for a more discreet purchase in an apartment. As time went by, sales became increasingly public. In fact, by the early 1960s, bootleggers were hanging out outside record stores, tempting would-be customers to buy their stuff instead of the “official” stuff.

Are there any historic controversies involving x-ray records worth mentioning? Were there any notable confiscations? Or proto-raves?

There were a couple of incidents where well-known figures were charged with making recordings on X-rays. There is a story of a famous radio presenter, who was a singer as well, who secretly made some recordings which then got copied and sold. He got into trouble — he was forbidden from broadcasting for a year. Apparently his popularity saved him from a worse punishment. There were also secret parties held by the stilyagi where they played jazz, swing, and rock ‘n’ roll. Toward the end of the 1950s, [recording on X-rays] became a cool, trendy thing to do. It was street culture.

“By the early 1960s, bootleggers were hanging out outside record stores, tempting would-be customers to buy their stuff instead of the ‘official’ stuff.”

Your website reveals the kinds of forbidden Western music that ended up on these recordings — Ella Fitzgerald makes an auditory appearance — but what types of Russian music were forbidden?

Most of the music on the records was, in fact, Russian. Emigré musicians, who were forbidden from coming inside the Soviet Union (because they were exiled or because they played music in the gypsy style) appeared on these records. Underground singers who didn’t have any other way of making records would also record on x-rays.

Is there a playlist somewhere of music forbidden by the Soviet government?

No, there is not! But books of forbidden songs were published each year. I’ve got one myself. It’s a fat book. Not a playlist per se, but a list of songs.

Independent of their historical context, these records are still beautiful objects.

Correct!

Did those bootleggers give much credence to the records’ aesthetic value? Or was there more focus on the practicality of the medium?

Buyers paid attention to the aesthetic value, as did the people who made them. You can tell by the way that some of the x-ray images are positioned: sometimes the spindle hole is right between the eye like a bullet. But the most important thing was the song and the sound. One of the bootleggers told us that unexposed x-rays [that had not been used] made much better sound recordings. Apparently, the sound was softer.

Selling illegal records in the same manner that one might also sell illegal substances brings to mind language some pre-digital rappers used to illustrate the demand and distribution of their mixtapes — “Somehow the rap game remind me of the crack game…” as Nas once put it. But how similar was selling illegal records in the Soviet Union to selling illegal drugs today?

We have to remember that in Stalin’s Age of Terror things were much tougher and frightening in the Soviet Union. Under Khrushchev, things got a lot easier and you were less likely to get in trouble. So I’d say selling X-ray records was pretty similar to selling soft drugs actually. It’s illegal, but the police don’t really care. It’s only serious if you’re caught dealing or growing.

The skeleton imagery on the discs echoes similar imagery from contemporary global punk movements. But the similarities between these bootleggers and other countercultural movements that gave rise to genres such as hip-hop, punk, and techno extends well beyond aesthetics. There’s a clear association between an intense, risk-seeking passion for music and a comfort with the macabre and the illicit.

I often make the comparison between x-ray bootleggers and punks. In the punk era, the flexi disc was a common medium because it was very cheap to produce. It sounded crappy but that didn’t really matter with punk music. Certainly in the UK, you had a lot of homegrown and small record labels. These were run by independent makers who took power into their own hands by refusing to rely on major record labels. An independent, anti-establishment spirit against the machine — I think there’s a great comparison there.

“I’d say selling x-ray records was pretty similar to selling soft drugs actually.”

Where do you see the spiritual descendants of these Russian bootleggers today? Are there places online where we see the same spirit manifest?

There’s always underground music but it’s difficult to compare this era with the contemporary West because music is really free and nothing is forbidden for us. That isn’t true in other parts of the world. There are modern places where the same culture and spirit exists. In the contemporary world the most obvious comparison is probably the narcocorridos that glorify narcotics trade and the gangs that practice that trade.