“Nepotism Is All I've Ever Wanted”: An Interview with BAKAR

When speaking to the British musician BAKAR about his new album, Nobody’s Home, and his upcoming US tour, I was reminded of two diagrams in my high school Physics textbook. In the section about Newton’s third law of motion – which states that “for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction” – there was an image of a flying bird, pushing the wind away with its wings, propelling itself forward. Beside it there was an image of a man jumping off a boat and onto a dock, sending the boat backwards. The key takeaway – that dynamic forces occur in opposing pairs – is helpful in understanding the acceleration of Bakar’s musical career.

Abubakar Baker Shariff-Far, known simply as Bakar, is the son of two East African immigrants, raised in the eclectic London district of Camden Town. Bakar started making music in 2015 by remixing tracks by King Krule, which he uploaded anonymously to Soundcloud. While you can still hear the “Krule” in Bakar’s crooning, his charming English accent and staccato delivery brings to mind Kele Okereke of Bloc Party, who Bakar notes as a key influence. While Bakar’s sound feels distinctly British, the stories he tells are of the diaspora, which is just one of many juxtapositions at the heart of his dynamism.

Bakar is both a rock star and a family man, who songs start mosh pits on tour and serenade his future sons and daughters. He has the confidence and charisma of a rapper, but has earned a loyal indie fandom with lyricism rooted in introspection and vulnerability. His first major hit, “Hell N Back,” matches a brooding tale of despair and heartbreak with a breezy track and chipper whistling. In the nascency of his career, Bakar found a mentor in the late Virgil Abloh, who cast him in Louis Vuitton’s SS19 show, alongside headliners Playboi Carti, A$AP Nast, and Kid Cudi. When Bakar was blowing up on social media, he didn’t even own a phone. Today he is a celebrated voice of young Britain because of his musical ability to articulate the shared experiences of being from somewhere else.

Bakar’s punk foundations are eternal, but the radical softness of Nobody’s Home is the mark of an artist who is unafraid to mature. It is a record about place and belonging, lineage and loss – the yearning for success and the need for disruption, about setting expectations and defying assumptions. When I spoke with Bakar about the feelings of absence he explores on Nobody’s Home, it came no surprise that he was deeply present.

Cassidy George: I know you didn’t have a phone for a long time, but it seems like you have one now?

Bakar: | just got one! I’m out of the phase of my life where I’m unreachable and an inconvenience. I’m trying to make things easier for people.

By making it harder for yourself?

Everything has pros and cons. Right now, the pros of having a phone outweigh the cons for me. I need to be contacted. I understand that…now [laughs].

Especially if you’re going on tour. Some musicians find tour to be very emotionally and physically taxing. Others find it energizing. Where do you stand?

All of the in-between shit and non-stop travelling isn’t really my vibe, but it’s so worth it. I am mostly just grateful for the opportunity. Most of the places we are playing are places we’ve never been to before. Getting to travel and play 1000 person venues? It’s still mind boggling to me.

And you get to play your new album.

It’s always so rewarding to perform new sets on tour. It’s like having a big slice of cake. New songs bring new vibes and new things for people to connect to. It’s weird because my music has just found its way [during the pandemic], even though we couldn’t tour. “Hell N Back” was a Covid-ass song. It came out in 2019, but its lifespan was really during lockdown. The first time I was able to perform it was at Reading Festival, last year. Now, with Nobody’s Home, I can’t wait to have that connection again and get to ask people: “What do you guys like?”

I think people were expecting to continue down the path of Will You Be My Yellow? with this record. But I reached a point in my life – and given everything that was happening in the world – when I was asking myself: “Who am I and what the fuck is all of this about?” I had to go away for a while and make this record just for myself, and I think people will appreciate what came out of that.

Why is it called Nobody’s Home?

Actually, I was really worried about the title! With all my past projects, I knew the title very early on in the process. For example, I knew I was going to make an EP called Will You Be My Yellow? years before I started making it. But with this one, I felt like I was treading water. I was constantly thinking, “When is it going to come? When is it going to come?”

I didn’t have a clear direction for this record. I just made the songs. I was scared to name it during the production process, because that would mean putting an umbrella on it. If I chose a title halfway through and wasn’t confident in it, that could affect the music I make. But the album has its themes and I just had to trust that those themes would take me there.

I eventually had that eureka moment. “Nobody’s Home” was the title I gave to a song I made at my house during lockdown, which didn’t make it onto the album. One day I was sitting there with my producer, looking at the track and thinking about the project. I just turned to him and said, “yo, NOBODY’S HOME!” He immediately understood.

The album is about my identity as a first-generation immigrant, where we come from, and what the immigrants of the future will look like. Of course, Nobody’s Home is also a double entendre for not being present, as in “nobody’s upstairs,” which is how I was feeling at the time.

Numb?

Yes. I think I was really able to articulate what that looked like for me on the song “Alone Again.” I say,

“Could you hold my head while I hold my breath

‘Til the feeling’s numb, ‘til their ain’t nothing left

Could you steal my lungs? Will you be my chest?

‘Til the feeling’s gone, ‘til the feeling’s dead.”

I had just lost significant people in my life. It was just grief, grief because someone close to me had passed and others had to leave my life for other reasons. It’s that scary feeling of: “Am I still feeling?”

Your mom is a major influence on your music. How would you describe your relationship with her? How do you think it has shaped you as an artist?

I think it’s really cool that she’s become a character in my music. That was the case with Bad Kid, too. I think it’s only natural because she was the person who raised me, but to answer your question, I think our relationship is still working itself out.

When you grow into your mid or late 20s, it can still be surprising that there are new things to learn about your parents. A new kind of relationship develops –and I think that’s sick. On the song “Youthenasia” I said: “I’ve been feeling nauseous lately, like my mama has become my daughter/ I wouldn’t change it for the world man, this shit is awesome.”

A lot of this record spawned from direct conversations with my mother and me thinking: “This is some extraordinary shit – and this story needs to be told!” My mom arrived in England as a refugee from East Africa in her late teens, and somehow just figured it all out. When you go back to where we come from, which I do, you realize that this is miracle stuff.

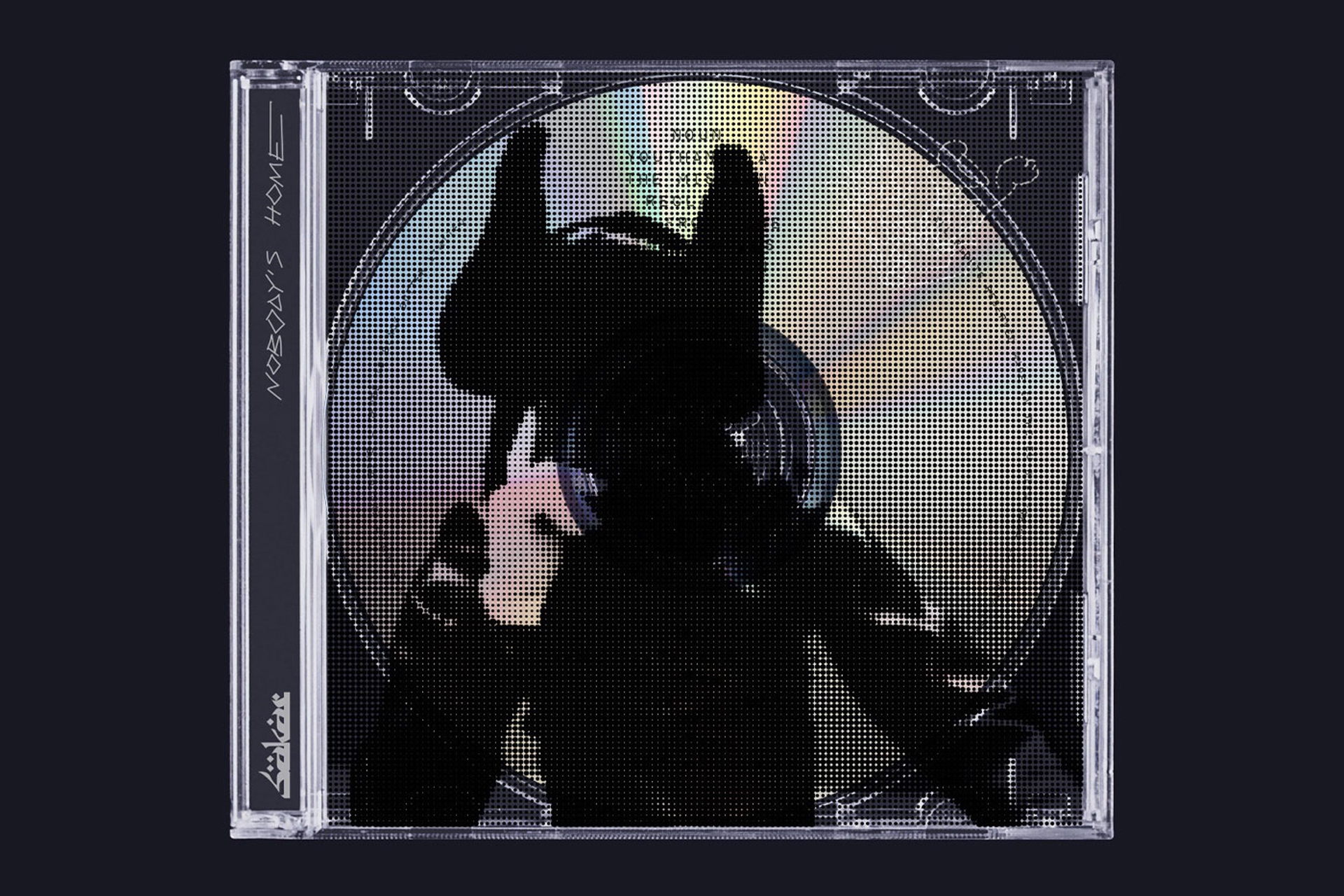

Limited Edition Nobody's Home CD, designed in collaboration with Virgil Abloh.

Limited Edition Nobody's Home CD, designed in collaboration with Virgil Abloh.

As the child of an exceptional person, and especially as a first-generation immigrant, there is tremendous pressure to succeed. Did your mom support your decision to make music, despite the lack of security that accompanies that path?

It was never really a conversation until I was already out there and doing semi-well. When my little brother started coming to my shows, she finally was like: “What’s he even doing over there?” I did worry about it to some degree because we are Islamic, and as Muslims, making music [professionally] is somewhat frowned upon. But my mom loves music, so I wasn’t super concerned. Now we are completely open about it and talk about my career all the time.

I think it was hard for my mom to support me on certain things because she’s so focused. Early on in life I wanted to be a soccer player. My mom could never come to the games, but that’s not any fault of her own. She was a single mother working loads of shifts. I think many African kids would agree that, outside of the education system and the things your parents tell you to do, they struggle to understand what decisions to support and how to support them. It’s just part of being a new person in a new place – and operating in a third world way in a first world country.

Anything I lack, I make up for elsewhere. I very naturally developed a creative support system outside of my immediate family. I was always lucky enough to meet people who had the presence of mind to understand what I was trying to do. Maybe I lacked support in other areas of my life, but with music, I always had people to bounce ideas off.

Like Virgil Abloh.

Yes, Virgil being the greatest. I was hesitant to share the Nobody’s Home CD we designed together, because it felt wrong to release it without him. But people reminded me how much he loved the record and that he really wanted this to happen, so I’m happy it’s coming out soon. It’s the right decision.

He and I did so many things together, even small things that people don’t realize. For example, Virgil was one of the main references for my US visa. That’s a type of collaboration in my eyes, too.

Big up to Virgil and his legacy. He continues to shine. Whether he’s here or not, the message lives on in so many forms, because he put so many people in a position to succeed and gave so many people gems of advice, love, care, and attention. I feel like a Virgil soldier at this point, for the love, light, and change that he represented. I think now that he’s gone, it’s our responsibility to go ever harder.

In your song “The Mission,” you say: “Do you know how badly I want some nepotism in my life?” But haven’t you have been embraced by some of the most influential people in the industry from very early on in your career?

I mean, facts! You’re right.

So what does nepotism mean to you?

I had that line, “All I want is for my kids to have some nepotism,” written down in my notes for ages. I think it’s potent. On the song’s outro I say, “All I ever hear is people talking about nepotism in a bad way,” and I think it’s an interesting concept to flip that around. There are people around me who directly benefit from nepotism – and I’m not someone who frowns upon that. It’s what you do with that nepotism that counts to me. Of course, there’s a level of sarcasm there, but that’s what we want from our art: to have a mirror effect.

I also just think the debate is funny. It’s popped up in London recently because this person called Molly-Mae Hague said something super stupid about “everyone having the same 24 hours in a day” to succeed. Then Kim Kardashian released a video telling women to “get to get their fucking ass up and work.” But it’s not that simple for us.

I’m not sure a word for what I mean even exists yet, but in a way, nepotism is what we are trying to achieve. We’re trying to establish a long line of people who are able to fly. The key word being “able.”

That’s your mission?

Well, there are different sections of the mission. There are shorter-term missions that have to do with music and creativity, which are a bit more superficial. But the over-all mission is to create a more equal platform in order for the people that I love and care about to succeed. My mission is to have children that are blessed by the opportunities their father worked hard for.

Family is everything to you. Is that a product of your faith?

It is definitely linked to being raised in an Islamic family. Those foundations are very deeply rooted. One day, you wake up from the first world fog and look around and see all of these beautiful beginnings. It’s a very humbling feeling and I think it seeps into my work.

It’s also linked to my own family structure. I didn’t grow up with my dad, but my mom has eight sisters. My mom’s dad also died quite early, so I didn’t know my grandfather, but my grandmother was very present. So, I was raised by loads of women. Women everywhere! [Laughs] That has something to do with it too. At one point, I wanted the cover of Nobody’s Home to be of all of my aunties, my mom, and me.

You and the nine women who raised you? Please don’t give up on that idea. I want to see it on the next album.

Logistically, it’s gonna be a nightmare! But you’re right, I’ve got to make it happen in the future.

On April 8th, Bakar will release 500 Limited Edition CDs of Nobody's Home, designed in collaboration with Virgil Abloh. All proceeds will go towards Abloh’s "POST-MODERN" Scholarship Fund. You can pre-order a CD here.

Watch the music video for "NW3" here.