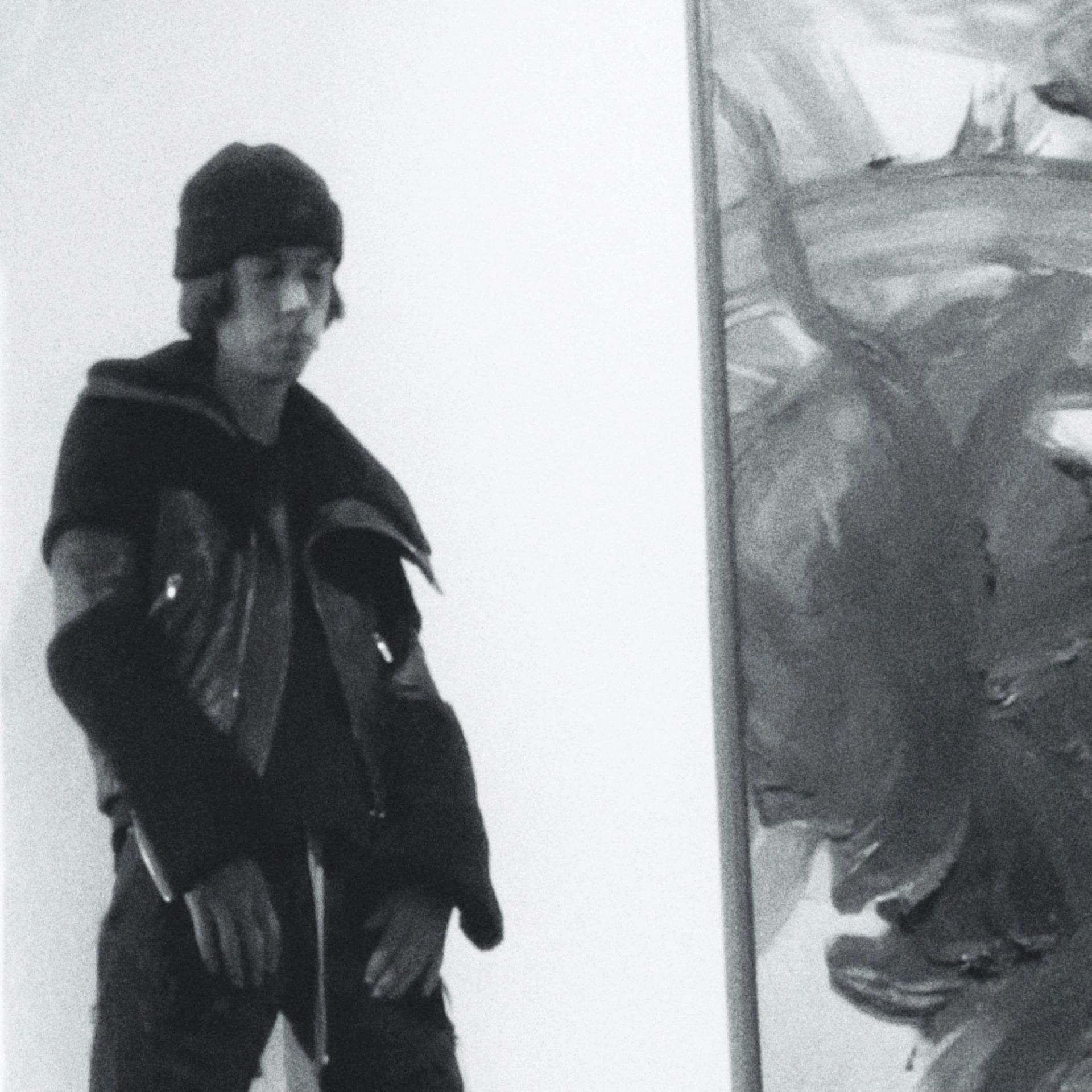

NICO BALLESTEROS: “It’s Risky to Be a Revealer of Truths”

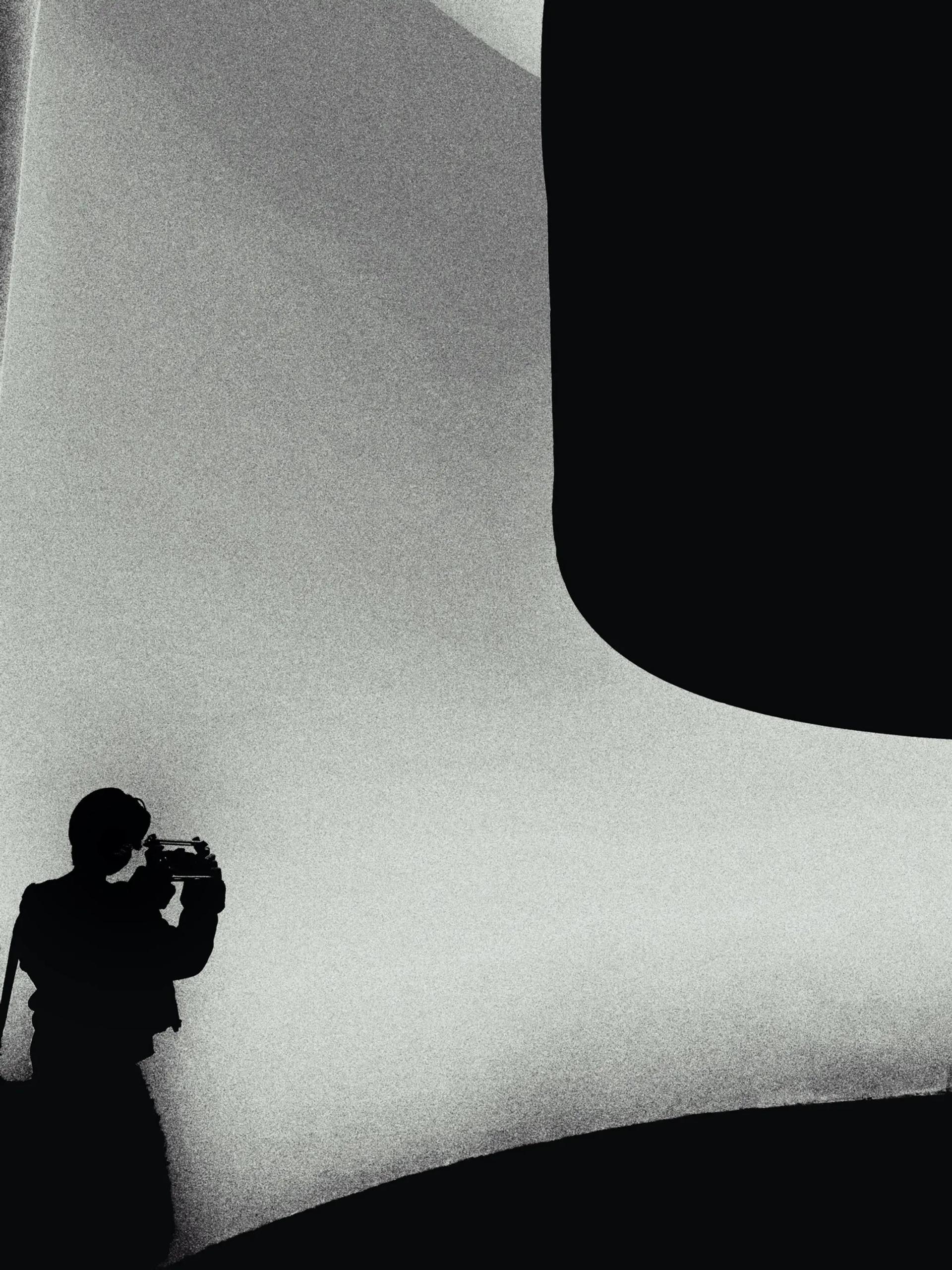

Image courtesy of Nico Ballesteros. Photo: Cian Moore.

Nico Ballesteros picked up his first video camera at age seven. “I borrowed my cousin’s camera and I pretty much never gave it back,” he told me on our phone call. “I don’t know where the archives are anymore, but I would essentially observe everything through that little lens.” Now 21 years old, the filmmaker is the shadow behind Kanye West’s vision, working as the rapper’s personal videographer and assistant director alongside Nick Knight for Jesus Is King: A Kanye West Film (2019).

More recently, Ballesteros directed the video for Playboi Carti’s “M3tamorphosis” featuring Kid Cudi, a collaboration off Carti’s many times leaked and much delayed 24-track project, Whole Lotta Red, which finally became available last week. “By age 12, I was finding reasons to visit the studios in LA, just to take tours,” says the Orange County native. “Then I went to an art-focused high school where I learned the fundamentals.” But the real exploration, according to Ballesteros, came from borrowing school equipment to shoot on his own time. “I had to find that fulfillment, because the classroom didn’t offer me enough ambition,” he says. Now, three years out of high school, Ballesteros spends around 15 to 20 hours behind the camera on an average day. A fan of Stanley Kubrick’s totalizing films – while we spoke, he was perched on a blanket rendered from a Kubrick still – and of an observational approach to documentary, Ballesteros caught up with me before the holidays to let me in on his process. “It’s risky to be a revealer of truths,” he said as we hung up. “But Kubrick was one. It’s why I draw so much inspiration from him.”

Octavia Bürgel: It sounds like the films you would make in your free time in high school became their own form of education. Would you say that curiosity extends to the work you are making now?

Nico Ballestros: My current mode of filmmaking has largely been observational documentary. Sometimes I’m working with a more standardized camera, but the majority of the time it’s an iPhone. That was even a whole step – not backwards, but sideways. When I first got the iPhone – even though I trained every day with cinema grade equipment – it was humbling. Because it’s such a light device, it operates like a director’s viewfinder. Physically, I was able to go 15 to 20 hours behind the camera on an average day, and I don’t know if I really would have been ready to do that with something more hefty. I’ve been doing that for the past three and a half years, since around two months after I graduated from high school.

You’re spending 20 hours behind the cameraa day?

That first small camera that I had – I brought it with me to Finland when I was visiting my family there, I was maybe 12. I was in the forest, going about this hike with the family – it’s all so Werner Herzog, but I didn’t really know who Herzog was at the time – and this miniature camera was allowing me to get that footage. The stigma around filmmaking is that it’s so technically based, and this stripped all of that away. I felt like I became a psychologist. Right before I started my current job, I had this hyper focus on Freud and Jung, and sort of clichés of modernity. We live in this post-YouTube, pseudo-intellectual world of anyone from Alan Watts to Jordan Peterson. In 2016 and 2017, I was really into that. I realized that those influences had prepared me, unknowingly, to analyze life – how to essentially be the fly on the wall, in the most voyeuristic way – absorbing all of these energies, perspectives, different personalities, and to somehow articulate them. I didn’t really have a plan to organize all of that data. I lost myself in the learning process of life – I wasn’t even logging footage, I wasn’t editing as I was going. It became more of a psychological study than anything.

Is observational filmmaking synonymous with documentary? Does it necessarily follow a narrative, or is its connotation more freeform?

The term is definitely specific to a documentary approach. There are essays on it, but in my view it’s an unobstructed viewing experience. No talking head interviews. You’re cutting a story from everyday reality – meaning you might spend years at a time just collecting data. I always remember the opening of Steve Jobs’ book – the author’s agreement – which I don’t have much context on, but it said something along the lines that he agreed to write the book only if he could show everything he saw. We live in these echo chambers of our realities – of how we’re defining ourselves, what our motives are, what our visions are. I believe that observational documentary filmmaking is like having a 10,000 perspective zoom-out from what’s really going on in our existence. If you make a documentary on a specific subject, it will have a specific scope. In a way, it almost becomes propaganda. Whereas an observational mode of filmmaking is very free thinking – it’s a reflection, a hero’s journey. It’s basically an existential crisis unraveling in front of your eyes. It’s asking more questions than it’s answering. But in that way, it allows you to become more human, more humble. You step outside of the box they put you in on Instagram.

“The stigma around filmmaking is that it’s so technically based, and this [miniature camera] stripped all of that away.”

You mention wanting to show everything in your practice, but I’d imagine that working with someone as highly publicized as Kanye might interfere with that approach. Is there a limit to the “everything” that you can show?

Right now, it’s not really about what I can show, and it’s more about what can be captured. At the end of the day, it’s not up to my jurisdiction. However, I believe in the mode of capturing. For that reason, it’s all up to interpretation, but it’s also all up to being a part of the experience that creates the “why”. Sometimes, to really understand an idea, the philosophy surrounding something, it can’t be revealed through just a one minute interview, or a product description. It’s really in the making. The prehistory of the documentary, or whatever it is, is important to the context of what’s happening in it. That has to come through in metaphors and conversations. Inspiration garners memories, and those memories are what breaks up this whole experience of space and time. That’s why it’s important to capture as much as possible – there’s beauty and there’s life in everything.

So you don’t mean “everything” in a material sense. Rather than applying to, say, the specifics of a given conversation, “everything” describes an accumulative approach to constructing narrative.

Yeah, it’s a feeling. It could literally be a moment of pure silence with the perfect composition. That’s something I forgot to mention about observational filmmaking: It’s also about the language of the camera. If you have a huge team doing a documentary, it’s not going to have its own architecture, it’s going to feel mass produced. Me going along this journey has its own language to it. Whoever is dedicated to this mode of filmmaking will have their own, because if we’re going around the world, and we’re learning these different things, it’s all going to manifest in a specific frame’s composition when the aha moment strikes.

How did you first connect with Kanye, and how would you describe your relationship?

Gab3 and Tremaine Emory – Denim Tears – jump started that for me back in 2018. Gab3 mentored me first, and throughout the process, Tremaine mentored me. And then, of course, Kanye did, but it was gradual. Coming into it, I would just film – very much like when I was a kid. I didn’t have a conversation. I think for the first year and a half, no one knew my name. No one even knew if I spoke. One person was like, “Oh, I didn’t even know you were American.” They thought I was picked up somewhere in Europe. I didn’t speak to Kanye directly for a very long time, but I was always in my place as the waterboy. And I still am – it’s something that I value. That iPhone on a stick is so humbling.

We live in a time where there is such a glorification of being a creative director. Prior to that, I think it was the glorification of entrepreneurism, tech startups, and that. It’s a beautiful thing to be a creative director – there are a lot of great examples, but I think kids forget what it means. And I’m also speaking to myself in the third person when I say that. Kids forget what it means to be an employee, to put in the work, to learn, and to foster a craft that is more than spitting ideas back and forth – which is very important but it only allows us to live in an ether of pseudo-intellect, rather than a defined role, a defined craft. Virgil was an engineer before anything else. That’s just an example to clarify what I’m trying to say. Everyone is so into color pallets, and textures, and mood board references – I don’t have advice for anyone, because who am I to give advice? But I will say that I really value my position of being the waterboy.

“Those influences prepared me, unknowingly, to analyze life – to essentially be the fly on the wall in the most voyeuristic way – absorbing energies, perspectives, different personalities, and to somehow articulate them.”

It’s true that social media has helped to codify particular aesthetic codes and attitudes.

Sometimes ignorance breeds innovation. We need to move into the why, and away from the how. I’m trying to figure out how to paint this idea. I feel like we’re all in a monastery, we’re studying every day, we’re all asking ourselves what this life is all about, and how to build worlds. Through that, I’m learning how to define reality, how to paint reality, and how to change it, too. Kanye is so passionate right now about building community, building worlds in a very literal sense. For me, it’s through film. The world is our set and we’re all unpaid actors. Everything that’s going on in life, I contextualize into a world for a movie or a play. But it’s all lateral movement, it’s all on an X axis – like we’re watching a Greek, or a Roman theater.

With Kanye, it’s a mentorship of world building. I started when I was 18, now I’m 21, so I’m becoming a young adult, becoming a man, becoming an artist. And the mentorship is definitely indirect – it’s not a one-on-one conversation about what it means to be an artist. We’re just living.

You have mentioned context a few times. I’m wondering, since you have this intimate working relationship with someone who is surrounded by a much larger cultural narrative, how you negotiate the space between those two experiences, in light of what you’re suggesting about context? Someone like me only has the cultural context to go off of, which affects, in turn, what we bring to the context you present us with.

I think time plays into that one. There’s always a stigma of who we were defined as, people are always trying to attach different ideals to you. I think we could architect the idea that there’s a public persona that represents how we got to where we are today, with all of the influences of one’s own self – the quantum leap of all those video game characters – to the current avatar. We’re always trying to pull reference and connect it to where we are now, but the dots don’t always connect. You can look back at the dots, like Steve Jobs said, but you can’t connect the dots looking forward. It’s like we’re transcending dimensions and levels. Not in an esoteric sense, just as a metaphor.

There’s obviously the Reddit fan base and all that, and people expect you to operate in certain ways if you belong to these little snippets of culture. It’s understandable enough, but it’s also funny for us to be in the realms of art, innovation, creativity, entrepreneurship – where we’re supposed to be breaking the rules, yet people also want to define you by certain cultural stigmas.

I was trying to do some research before we hopped on the call l, and I kept running these Reddit forums posting pictures of you, asking “Who is this guy?” Despite having however many followers you have on Instagram – in the thousands – there still seems to be an air of mystery around you online. It reminds me of what you’re saying about being content to be the water boy – to be out of frame, so to speak.

Oh, I absolutely love being out of frame. I’m here for the information, not for the validation. I operate best in the unknown. I’m not one of these clearly defined, one dimensional, internet slap sticker brands. So how am I supposed to brand myself? Identity is a whole new exploration for our generation. If we can accept the quest to understand our identities in reality, why are we expected to define ourselves in one way online? This persona – I didn’t make it purposefully, I was just working. I’m so busy living real life, filming every day, or editing every day, or reading a book, or doing nothing – whatever it is, that I don’t view my existence as important enough right now to put work out there. People can be so aggressive with wanting projects, or wanting to see more, or not believing. I don’t care if they don’t think I’m a good filmmaker, because I’ve been doing it now for more than half of the time that I’ve existed on this planet. Most filmmakers don’t even make their first film until they’re 27. George Lucas made THX, the student film, when he was 23 and he made the feature when he was 27. Sorry I’m not shooting music videos for every rapper – because at the end of the day, that’s the unfortunate reality for a lot of film students who go to USC film school and then they shoot a rap video. It’s like, “Wait a minute, are we supposed to make music videos? Or are we supposed to make films?” That’s not a slight at those career pathways at all, because we all have to make negotiations like that.

I’m currently working on my personal thesis, which is going to be a narrative feature film. It’s going to be based in science fiction, rooted in an exploration of sustainable agriculture, and human consciousness, and their relationship to our food supply chain. I’m going to land these experiences on screen, but in the process I’m also learning about communities, and about farming in real life. Do you think Stanley Kubrick would be sharing everything he shot on Instagram right now? Also, Netflix – do I even want to exist on Netflix? I go on Netflix and it takes me like, a year to find something that I want to watch. Maybe I’ll do one thing that I’ll be remembered for, or maybe I’ll do nothing that I’m remembered for, but I’m not in the mindset of legacy. I’m more so asking myself, “What do I feel needs to be said?”

You certainly aren’t deluded about the fleeting nature of success, but I’m curious about how you might define it.

Success, for me, would be to create a film that allows humanity to have some kind of existential awakening. But even though that’s my ultimate goal, it can’t be my intent going into making a film – it might be the least expected film in my discography that elicits that response from the audience. People expect you to have answers to the chaos in the world, and I think that eventually, I will begin to address it in my future work. I want to tell a story with lateral movement to strip away a lot of these technological advancements, to tell a very primitive film story, to allow chaos to ensue – but mostly to really explore humanity’s big questions. I’m creating a film for my own personal understanding of my, our, collective existence, but also to inspire a next generation of filmmakers as well. Even if I can’t provide the answers, I value the craft more than ideas. Advancing the craft – whatever it means – is still primitive, without being so technological that it strips away the pure essence of the film. We come from cave painting, we come from telling stories around fires, and those stories we passed on and they became written and performed on stages and in auditoriums, and theaters. To allow these existential questions to exist in our dimensions: That’s my goal. Because they’ve been here since before we’ve been here. It’s more about finding a way to let technology allow the ideas to exist in new ways, without being gimmicky. I don’t think VR or AR is the answer. I don’t know what the answer is, but I think there is a next step to cinema that we haven’t even seen yet.

“I think there is a next step to cinema that we haven’t even seen yet.”