SHUANG LI : Intro to Civil War

“The changes within neoliberalism that we are witnessing are characterized not only

by the transformation of ‘gender,’ ‘sex,’ ‘sexuality,’ ‘sexual identity,’ and

“pleasure” into objects of the political management of living, but also by the fact

that this management itself is carried out through the new dynamics of advanced

techno-capitalism, global media, and biotechnologies. We are being confronted

with a new type of hot, psychotropic punk capitalism. These recent transformations

are imposing an ensemble of new micro-prosthetic mechanisms of control of

subjectivity by means of biomolecular and multimedia technical protocols.”

Paul B. Preciado, "Testo Junkie: Sex, Drugs, and Biopolitics" (Trans. Bruce Benderson, Feminist Press, 2013)

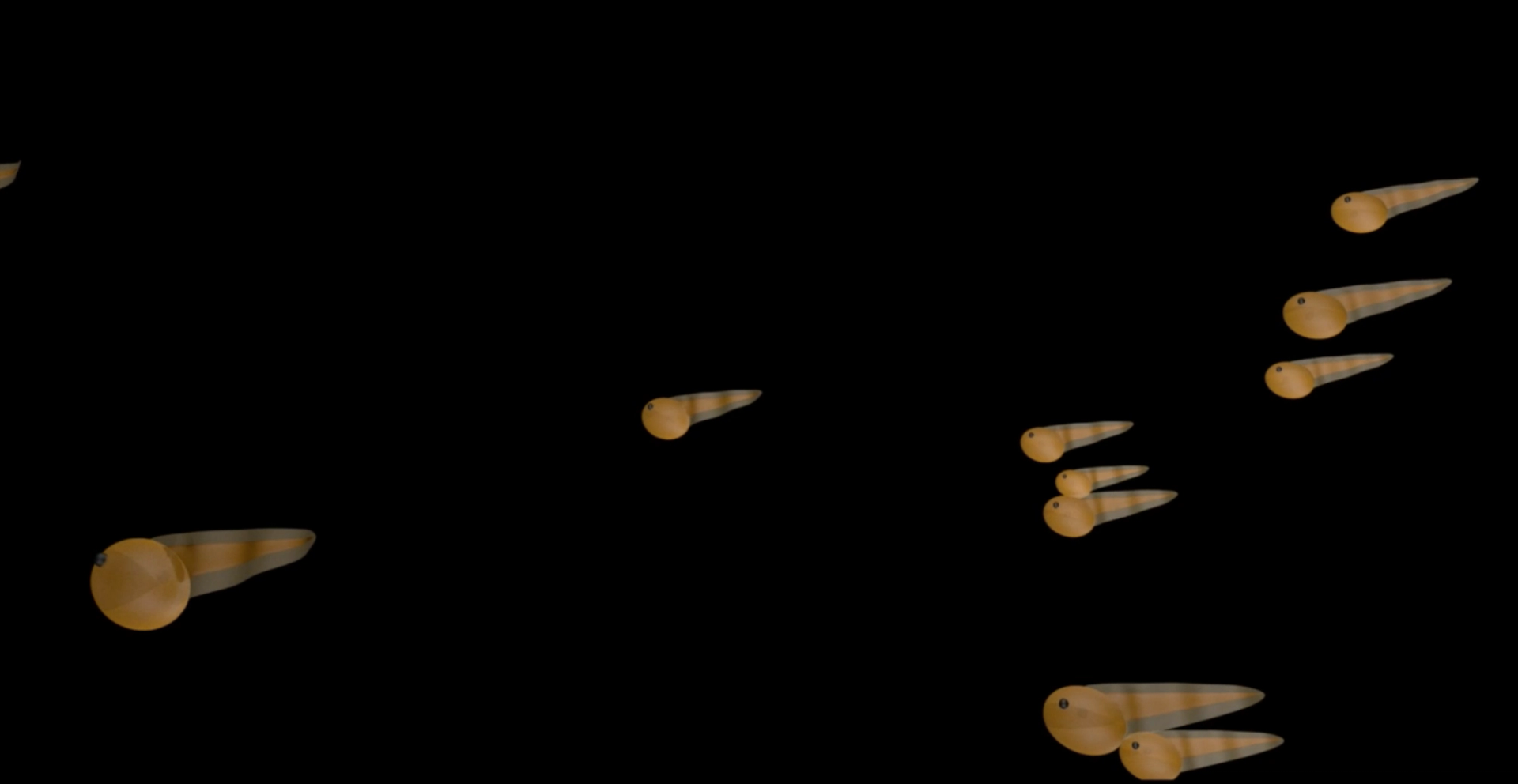

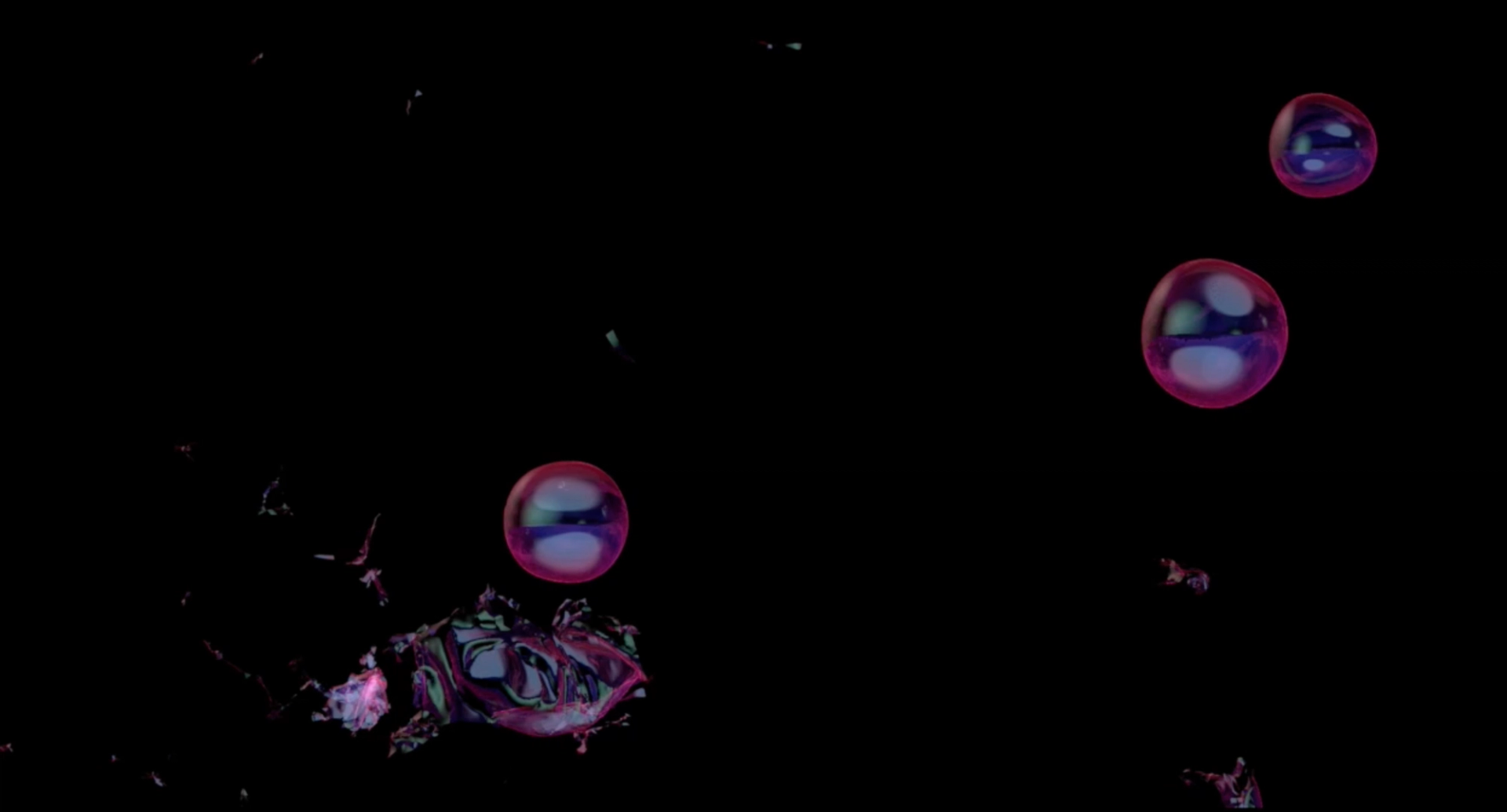

Shuang Li, INTRO TO CIVIL WAR, 2019. Video Still. Courtesy of the artist and Open Forum.

Perhaps it’s not immediately obvious from its title, but Intro to Civil War, SHUANG LI’s first solo exhibition in Europe, is about sex. Currently on view at Berlin’s OPEN FORUM, the show – named in reference to a book by French philosophy collective Tiqqun –combines video, sculpture, sound, and installation around an imagined dialogue between a present-day AI sex doll and the ancient concubine on which she was modeled. The result is a part-historical, part-futurist study of how structures of power regulate our sexualities, our gender identities, and our bodies in a globalized, digitized world – themes the artist, based in Yiwu, China, has explored before. (Her 2015 performance Marry Me for Chinese Citizenship featured clothing and bags emblazoned with the work’s slogan-like title, .) Citing theorist Paul B. Preciado in the statement for this latest show – which features 3D animations of tadpoles, music by Eli Osheyack, and swirling holographic projections – Shuang Li doesn’t strictly condemn the current state of control and consumerism, or how we got here. Rather, despite the ostensibly cold, faceless backdrop of biotechnology, surveillance, and post-digital interpersonal connections, she locates humanity in our increasingly complicated (and persistently transactional) sexual status quo. Her artistic process of distillation, she reveals below, is not just facilitated by digital cultural research. It is informed by a personal experience of technology, via bootleg Nintendo games and Myspace friendships, among other things.

This is your first solo presentation in Europe. Was your experience in or of Berlin influential to how you presented or contextualized the work? More generally, what were your impressions of the city and its creative scene?

In terms of the presentation of the show, Nick [Koenigsknecht, founder of Open Forum] definitely helped me a lot contextualizing my concept. We had been talking about the show for months and he had been offering me perspectives that I couldn’t see on my own.

I’d never been to Berlin before, and the creative energy is definitely very different from Shanghai. Berlin reminds me a lot of Bushwick, but I’m so inspired by how the city memorizes history. And for this trip I actually met up with one of my Myspace friends for the first time. We met on Myspace around 2005, then we moved to Facebook, then Instagram. It’s magical to see her in the flesh in Berlin.

Your work engages many media – video, sound, installation, even the medium of the dialogue or story. How do you go about choosing, or how are you drawn to certain media to convey your messages?

Most of the time, the whole process feels like driving up a winding mountain road. You keep speeding up, and at one point the car breaks the barricade of the roads, flies out from the curve and off the mountain. I can’t drive, but I imagine that is what driving off a mountain feels like from the video games I’ve played!

I always have one general concept that I have in mind and have been researching intensively. For the work at Open Forum I had been researching ancient concubines. So much had been said about them, but no voice came straight from their own experience. For this show, I wanted to make the gallery space into a shrine to channel them. At one point I read in the archive that concubines were made to drink tadpoles, which were believed to prevent pregnancy. Then I started looking at tadpoles, which actually look like sperms. I think that makes it a very interesting imagery to play around with. So I commissioned 3D animations around the imagery and decided to put them on the holographic fans, trying to build this shrine with future-looking technology – and printed shower curtains.

Shuang Li, INTRO TO CIVIL WAR, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Open Forum.

Shuang Li, INTRO TO CIVIL WAR, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and Open Forum.

There’s a certain human quality to your work, even though there aren’t strictly speaking human forms or figures – how do you use the “cold” technological landscape as a place for a more personal voice, touch, emotion? And are you using your own personal experience as a way of achieving that?

I guess for some reason I’ve always been an inside-outsider to all the mediascapes that I’ve engaged with. I grew up in a small town in China where there was basically nothing to do, so I was on Internet all the time – mostly on YouTube and Myspace – before I could actually speak English. I didn’t know what was going on. What I could understand back then was only the interface, pictures, and music.

The other thing that I hold so close to my heart was dakou CDs – the kind of CDs that were sold as trash to Asia after punching a hole in them and stripping them of their commodity value. But somebody figured out the hole wouldn’t really hurt the disk, and started selling them really cheap, like two dollars for a CD. I got to know My Chemical Romance and Marilyn Manson through these cracked CDs, and felt really connected like every other emo kid – like, “Ah somebody finally understands me.” And it was also through their music that I learned English.

As a kid, one of the most luxurious things I had was a knockoff Nintendo and the pirated video games. One of my favorite games that I was obsessed with was called Jackal, which was basically driving around in a tank bombing people and buildings in the jungle. But not until recently did I learn my favorite game was based on the Vietnam War.

I did literature for undergrad and media studies for grad school, where I tried to bring in these outsider points of view. I guess these technological landscapes have never been “cold” to me. Always being the outsider also gives me another perspective looking at them, but I’m also well aware of the Western structures – the etymologies, and the academic system that I graduated from. At one point I struggled to break free from it in my work, which might be impossible, so now building upon that to develop my own voice is more like what I have been trying to do.

“Technological landscapes have never been ‘cold’ to me.”

Shuang Li

You highlight some urgent and deep political and social issues, but the work does not feel preachy or didactic. It feels connected to experience or feeling. How would you describe your approach to themes such as these? As an artist in 2019, does it feel like a duty of some kind to take on issues of political and social significance, for example representing marginalized bodies or communities?

I do feel like an artist has social responsibilities toward an increasingly diverse and global audience, as opposed to a small elite, art-inclined group of people. I know I can’t claim to represent any community – not even my own – but I always want to connect just personally, and that’s the departure point I take in a lot of my works. I remember studying in the US, there were a lot of people my age whose parents or grandparents would have some stereotypical impressions of Chinese or Asian people in general. But when I went to their homes and had dinner with them, they saw this stereotype turn into flesh, and we usually had nice conversations.

I’ve been studying the Muslim population in China, and plan to make new works about that in the coming year. I’m definitively an outsider to their culture but I do feel connected, particularly in terms of the situation of women. Now I live in a town in China where there is a big Middle Eastern population and there is this women-only gym. I usually feel so exposed at the gym, only in this space I feel free and empowered.

Shuang Li, INTRO TO CIVIL WAR, 2019. Video Still. Courtesy of the artist and Open Forum.