Wong Ping’s Golden Shower

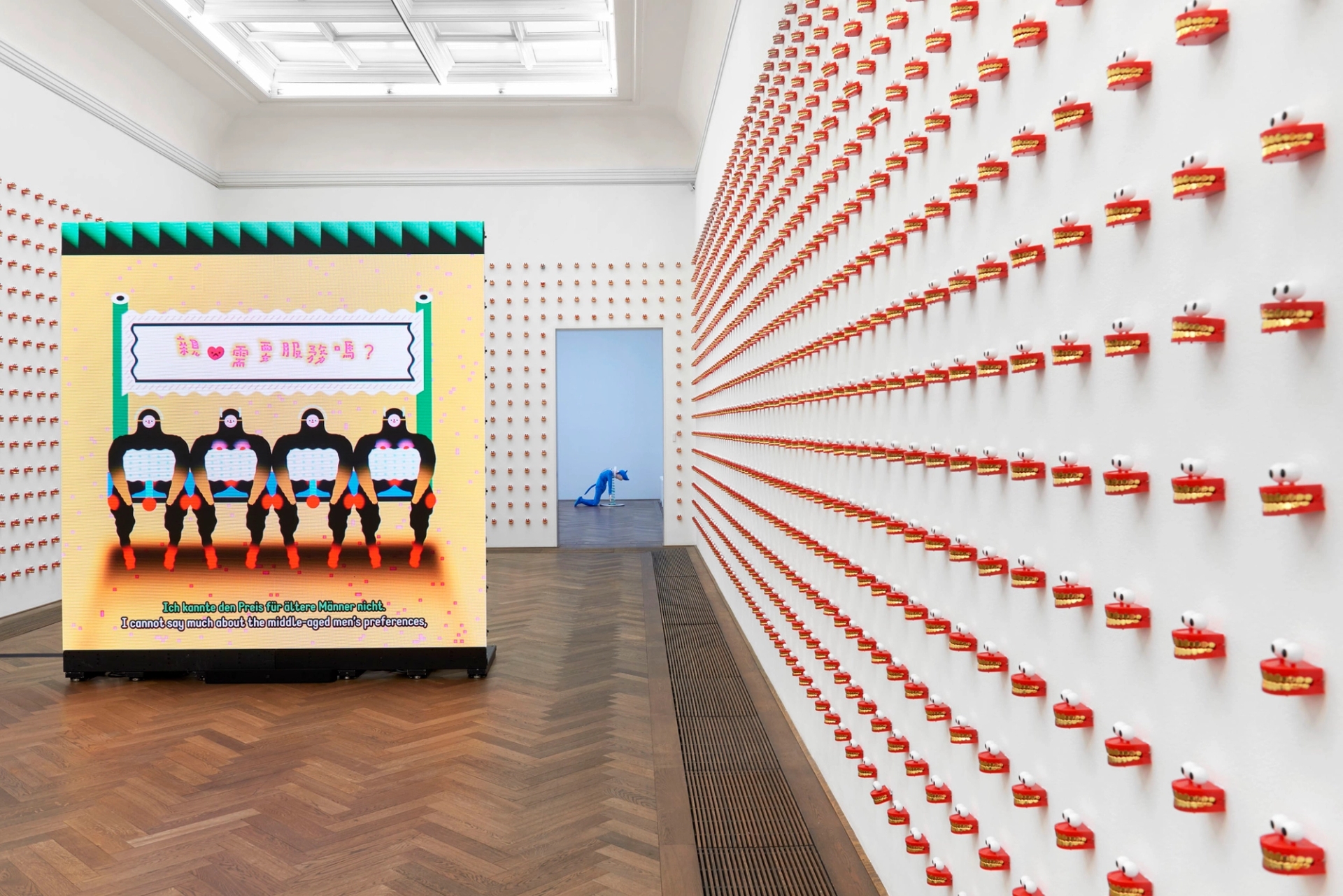

Among the many deviant funhouse objects that fill Wong Ping’s Golden Shower, newly opened at the Kunsthalle Basel in Switzerland, are roughly 4,500 sets of golden wind-up teeth. These are props from the Hong Kong native’s latest film – Dear, Can I Give You a Hand? (2018) – a macabre 12-minute animation in which a horny widow steals his daughter-in-law’s panties, is attacked by flesh-eating ants, and crushed beneath a pile of gold teeth.

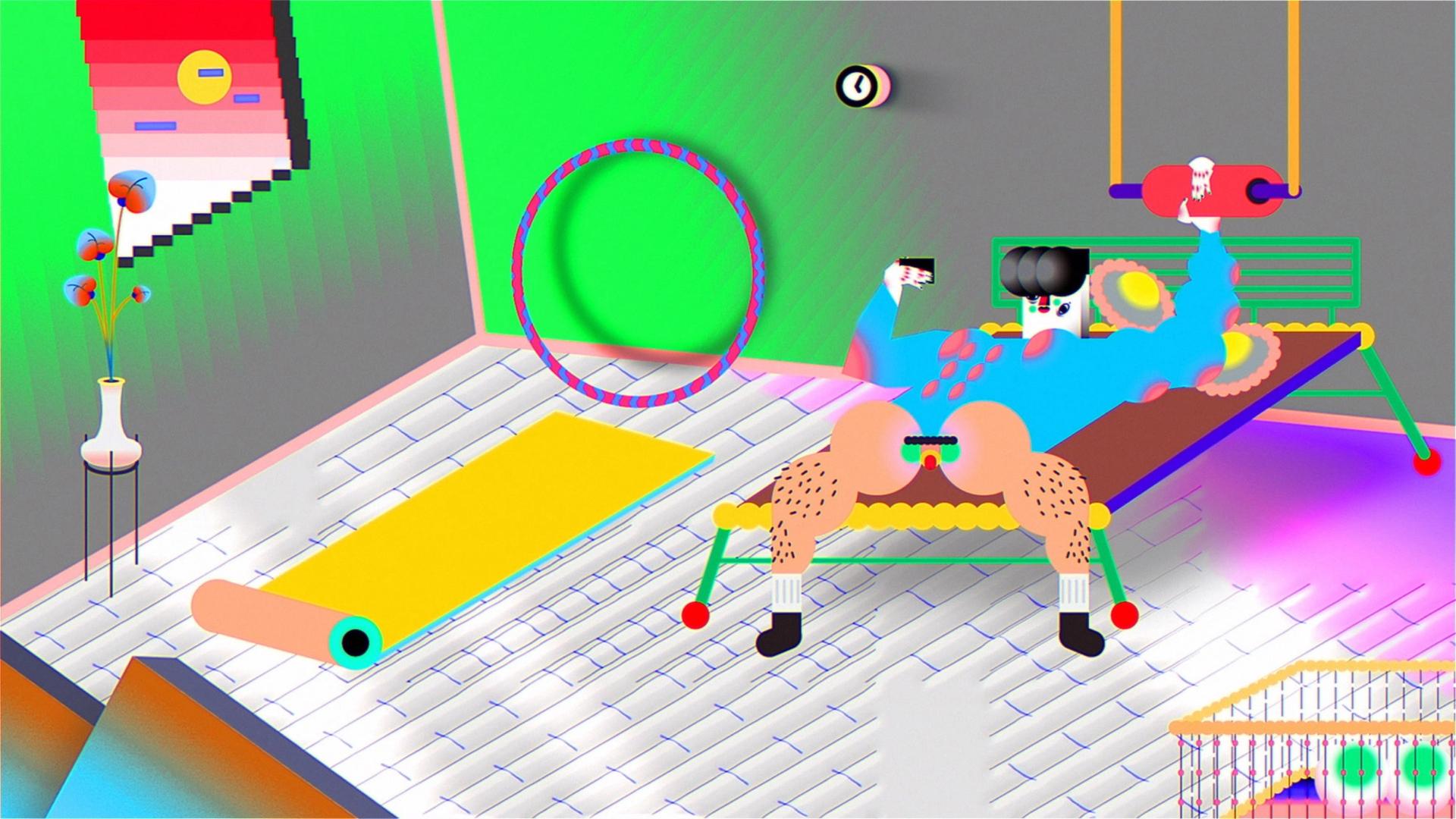

Wong Ping is an artist – though despite this major solo presentation in Basel, prefers the title “comedian.” He wasn’t squeezed through the art school funnel, but studied design, and started out working in postproduction at a local TV studio. After creating an animated music video for a friend’s band, he began to combine stories he’d been writing with an idiosyncratic visual style: simple geometric shapes, bright tonal gradients, kinetic rigidity, and deadpan confessional narration. If the results are shocking, they’re shocking for their openness: they make public the unspeakable internal monologue, private desires, and bitter fantasies – everything deemed dirty, icky, and perverse, softened by a visual language equally suited to children’s cartoons.

What the films – and the exhibition – capture best is what publisher and critic Michael Heitz refers to as “the relationship between instinct and culture,” a modern panopticon in which individuals suffer “under the grand imperative of enjoyment.” Tinder, internet pornography, sexual liberation: both signs of unrestricted freedom and drivers of atomization. And what better location than the dense, technologically-wired high-rises of Hong Kong to serve as a visual laboratory from which themes of alienation and urban loneliness emerge. Many of Wong Ping’s films have their origins in reality – and they often contain a moral kernel, as weird or difficult to discern as their morality might be. (His ongoing current project is a series of Aesopian fables, the first of which debuted at New Museum triennial in February 2018.) Dear, Can I Give You a Hand? began after Wong Ping saw an old man throw out a full bag of VHS porn – and from this, the film leads to a type of happy ending. Our horny widow enjoys a post-human afterlife in a “online cemetery,” out of which he escapes into the data network and onto the servers of the porn site that hosts his own old VHS content, uncensored and license-free. “I spend an entire week masturbating,” he tells us, as the cycle of pleasure and despair resumes. “I am truly grateful once again.”

032c spoke to Wong Ping the morning after Golden Shower opened in Basel.

How’re you doing?

I’m great! I had a really great sleep last night.

Oh?

Yeah. I didn’t go too hard. I spent so much time on the exhibition that I passed out after the opening.

But it was a fun evening?

It was great. A good adventure. I don’t think anyone would answer you: “The opening was bad! It was so bad!”

I mean, I overshare, I probably would. I saw on your Instagram there were dildos on the dinner table.

Yes, someone from Last Tango, the art space in Zurich, drove over and brought me a gift. A dildo.

It’s quite a phallocentric exhibition. There’s a sort of penis video viewing tower.

Yes! Very true.

This exhibition is your first institutional solo show and you’ve made so much stuff for it. Could you describe some of the objects?

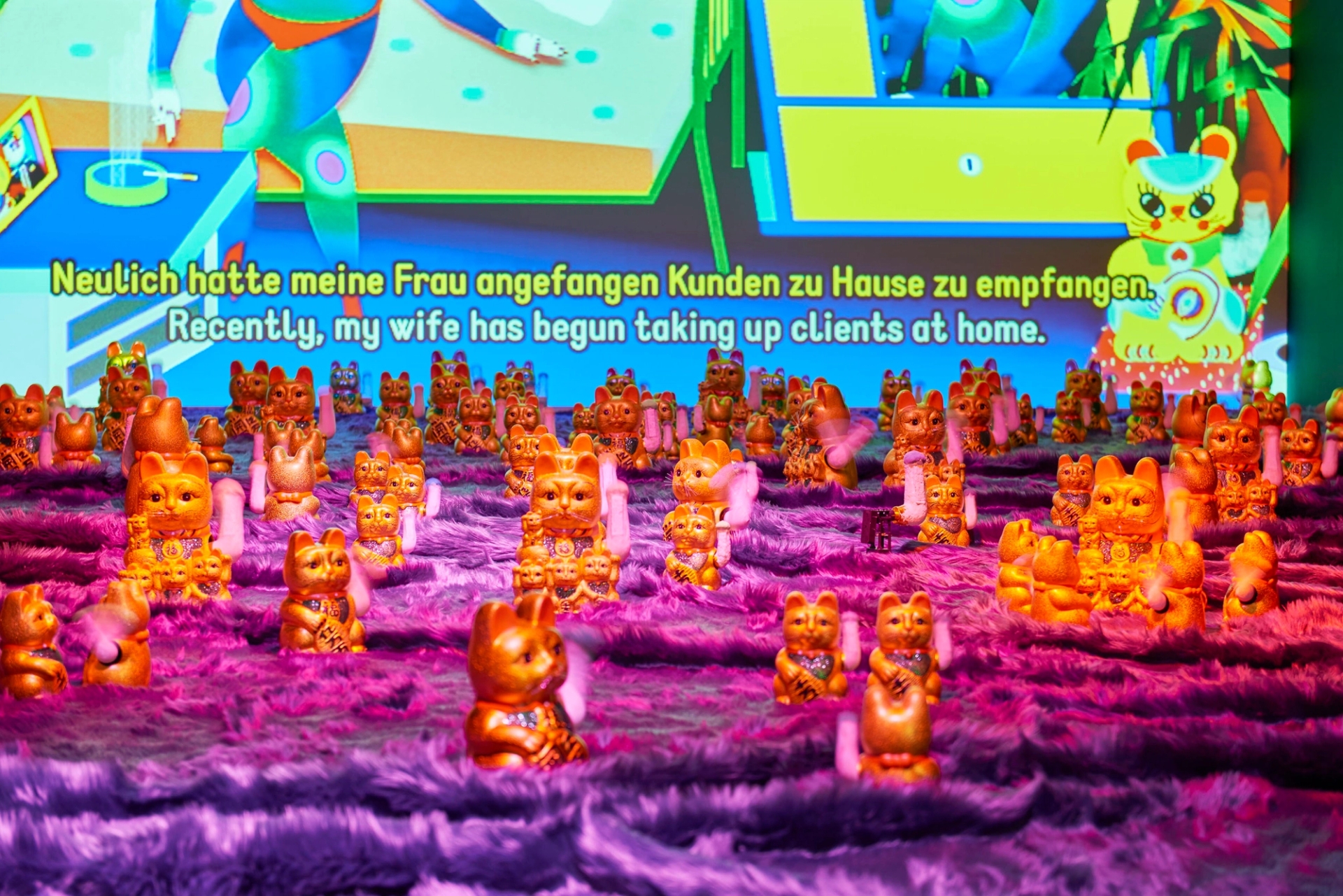

In the first room, the film Dear, Can I Give You a Hand? (2018) is showing along with an installation of around 4,500 wind-up toy gold teeth – objects which expand upon the content in the video. In the third room is my film Jungle of Desire (2015) and lucky cats with dildo hands – penis hands – which is also a concept drawn from the video. The video was inspired by reading about sex workers in Hong Kong in the newspaper. The cops were taking advantage of them, threatening to arrest them in exchange for a free service. Fortune cats are usually seen in stores where they are used to bring in custom. So in the case of sex workers I think it makes sense to put a dildo there, swinging back and forth, waving to customers. Before 2015 I would just upload videos online. Jungle of Desire was my first film for an art show. After the show I actually donated about 20 or 30 of these sculptures to a charity that helps sex workers.

You donated the cats with penis hands to sex workers?

Yes. I donated them.

Fab.

So they can be in the reality as they are in the video. That’s what I hope for.

Jungle of Desire was the first film I saw of yours, and I detected a “fuck cops” attitude in it, but I had no idea it was drawn from reality.

Many of my films aim to fictionalize reality, and they’re also personal, so yeah that was a fun experience back in the day.

I think a lot of the stronger responses to the work come about because the imagery and playfulness of what you’re doing makes people think of cartoons and media aimed at children. Then you have subject matter which is not traditionally what we’d think of as being appropriate for children. What draws you to this sort of aesthetic?

I always say that the aesthetic comes from my inability to make animation like Marvel, or Pixar, or Disney. I think it just developed as I tried to push the limit of my abilities, my skills. That’s weird to say: “I push the limitation to its limit.” I did every aspect of the video myself. I didn’t think a lot about how to set up a style. This is the only thing I can do. I can only draw circles. I can only draw squares. I didn’t really know how to draw until I was like 24, 25. Simple shapes is just the best I can do. I’m not a huge fan of cartoons and animation, actually. You know, I like some, Adventure Time. I loved reading Japanese comics when I was young.

Are you a fan of fiction?

I think I’m a big fan of storytelling and drama, more like Woody Allen, just keep talking throughout the film, non-stop talking, chatting. One of my favorite directors is Yorgos Lanthimos – especially Dogtooth. I think his writing is great. I like how it’s in reality, but also it’s crazy, it’s fictional. Sometimes we can write things that aren’t realistic, but I like the control and balance of “it can happen.” It’s real, but it’s also weird. I don’t know how to describe it.

Maybe I use animation and cartoons so that I can comfortably express myself with this kind of content. If I made films out of live shooting, that wouldn’t be as pleasant to watch. I mean, if you think about fisting in a cartoon versus fisting in a real life movie, these are different things. One time there was a guy who told me he felt uncomfortable and weird about people looking at the film Who’s The Daddy (2017) and smiling or laughing when the content was so horrible and terrible and scary. He wasn’t happy with that.

Your latest work takes the form of fables: Wong Ping’s Fables 1, made for the New Museum triennial in 2018, and now Wong Ping’s Fables 2 (2019). The form is ancient, and used to deliver a moral. In the fables you make, the moral pops up at the end, even if it’s at an angle to the film, and what that moral is might be confusing. But it’s the form. The message is contained within a narrative.

These fables are not super personal – I wouldn’t put my emotions or something I’ve been through in them – but wanted to start something appropriate for children so I went to the library to do some research. Aesop’s fables are super famous in Hong Kong – as are Anderson and Grimm’s fairy tales – but I don’t think anyone has actually read them. I found that in Aesop all the stories are very positive and we can all agree we have to be a good human being and behave, but in this modern age I’m kind of sick of this kind of morality. It’s not practical in the real world. Things are more complicated. We all know we have to be a good human being, but somehow maybe you couldn’t. I would like to tell the truth. I want to write some weirdly-angled fables that are almost like an immoral lesson, actually. I hope I can have a whole collection and keep on going and be like Aesop.

What we definitely do see is desires which are totally distorted by the culture in which these isolated people live. You have alienated people compelled by natural urges, often sexual, and then you have technology, the attention economy, trends. The films feel very Hong Kong to me in the sense of kinda claustrophobic but also very bright (like Mong Kok, where it’s blisteringly bright at 3AM). There’s also the density: there are people on the other side of the wall but you’re not actually in touch.

It’s crazy that Switzerland has the same population as Hong Kong. A city compared to a country. It’s crazy.

And it’s all vertical.

No sky at all. It’s obvious in a way, because I live in HK most of the time, but when people say my videos are very Hong Kong I would think, why? I never draw anything very typically Hong Kong – like dim sum, or specific landmarks – but of course I’m glad to hear there’s some spirit of Hong Kong. I just can’t tell because I’m in it most of the time.

I think it’s an atmospheric thing. There have been a few pieces about your work in which people have really focused on emojis and dating apps and stuff that’s very much of the present – but I also felt this timeless alienation. Male adult alienation for the most part.

A weak male.

I had “beta males,” the internet’s self-identifying and self-flagellating cucks and incels. The men in your films have a lot of crazy ideas, but they don’t carry them out. They’re only daydreams. What draws you to that kind of character?

I think it’s living in society – I mean, not in Basel or Berlin maybe, but in Hong Kong those frustrations come very naturally. And y’know in the modern age with dating apps there’s a lot of chance out there, but also more depression. How come? We’re freer than ever. We have apps so we can meet anyone possible in the world – yet I think the frustration comes when we ask why we still cannot get a happy life or why is it so hard to get what we want? Living in fast-paced Hong Kong, I think you can feel it if you live there long enough in the city crowd. The character comes very naturally from inside.

I always say sex is only the language in my videos, the message I want to bring out is more than sex, but actually this is a good balance. I would like to make a video that lasts, not just simply fuck around. They need to have something to say in order to justify me suffering through the animation process. But also I don’t really mind if people just see the sex part.

It ties into a lot of stuff being said about this generation – like, the total freedom on the one hand, and the fact that the number of people having sex is lower now and not so many people want to do drugs. Anxiety is through the roof and the drugs people do want are from pharmaceutical companies. I definitely think that is coming through here it’s like that millennial alienation – these are media clichés but there’s some truth there. If you contrast it with our parents’ generation, we’ve evolved to a different set of expectations for life. A lot of is unconventional and quite hard to explain – so maybe we need fables.

Totally. Y’know, I send my parents memes and they don’t understand. They ask, what is happening? Why this picture? And then I need to break down all the funny parts and explain why this is funny. I stopped sending.

I noticed that on your Vimeo you describe yourself as “a comedian.” Is that humility or are you serious, is that how you see yourself?

I don’t feel comfortable calling myself an artist because I don’t know what “artist” means. But comedian? I can do that. The hard part is when I put “comedian” on Tinder and people like me because they think they can date a comedian. I have to explain “No, I’m not an actual comedian.” Then they’re disappointed and think I’m cheating – lying in the app. That’s not a very good first impression.

That degree of irony doesn’t translate on the Internet, I’m afraid. This is why you can’t write anything on Twitter – or at least you can’t make a joke on Twitter – it’s not going to work.

I really enjoy watching stand-up comedy but I think there’s been a trend where comedians have become too scared to do it anymore. My work is very similar to stand-up. In a one-hour set they may throw like 20 or 30 different stories, line after line, punch after punch, with a little meaning to each line. They’re supposed to be funny but behind that there is a message other than just being funny. I think it’s quite a similar process when I’m making my work. If you pick one or two lines randomly from each video I think I can tell you what is going on behind those two lines.

When I look at the big hit comedians’ sets now I think they’re so boring. They’re scared – I mean, I know why they’re scared, and maybe it makes sense, maybe it doesn’t. In Hong Kong it’s less extreme. I don’t know why but in HK there aren’t many public figures who would have the bravery to say honest stuff begin with.

Wong Ping will take part in an artist’s talk with Kunsthalle Basel director Elena Filipovic on April 28. Golden Shower is on view until May 5, 2019.