Brenda’s Business with RICK OWENS

Rick Owens is business. In a fashion industry dominated by large conglomerates such as LVMH and Kering, Rick Owens still owns Rick Owens. 80 percent of Owenscorp, an independent industry giant that generates hundreds of millions annually, belongs to the designer. His label is known for a dialogue between his unique expression of elegance and beauty and what he calls a “raging ego.” The entry-level purchase to become part of his universe might be a bulky sneaker. However, if you care to look further, the loyal brand’s customers keep coming back for its delicate, meticulously constructed creations. Rick Owens makes you feel powerful — not through simple logos, but designs that emphasize the idea of understated luxury.

In our interview, we decide to focus on an era before he was known to be the unofficial Lord of Darkness and a rumored post- apocalyptic cult leader: a guy on Hollywood Boulevard, emerging out of patternmaking, trying to get buying appointments for his fashion label.

BRENDA WEISCHER: Ideally, this Interview is like one of those stereotypical Hollywood movies about becoming successful — mainly focusing on the struggle. The movie ends with the protagonist walking out on stage, standing in front of a giant cheering crowd. That’s the kind of sentiment I want. College dropout, Hollywood Boulevard, Charles Gallay, Maxfield, the Kate Moss leather jacket. Maybe we end it with your 2002 show.

RICK OWENS: First I went to art school, but then I couldn't really afford that. I just lacked the intellectual stamina to be a serious artist, and I was intimidated by the theory classes, which were such theoretical bullshit. So I dropped out and got a job. I was an office assistant for an architectural illustration firm. It was a very chic environment for a young guy like me. I did that for a while to survive and support myself. Meanwhile, I went to trade school to learn patternmaking, which came to me quite naturally. Then I got a job at a manufacturer that did knock-offs. They would bring me in a Claude Montana T-shirt or a Versace jacket, and I would copy the pattern for them. I did that for a few years until I got introduced to Michéle [Lamy] and was offered a job as a patternmaker at her company.

BW: Is it true that you got introduced to Michéle by your then-boyfriend? Did you already design there or just did patternmaking?

RO: I think I condensed this story for interviews. I don’t actually remember us really being boyfriends, rather best friends who fucked every once in a while. Michéle had asked Rick Castro, my “boyfriend,” to design a menswear collection for her, and he brought me on as his patternmaker.

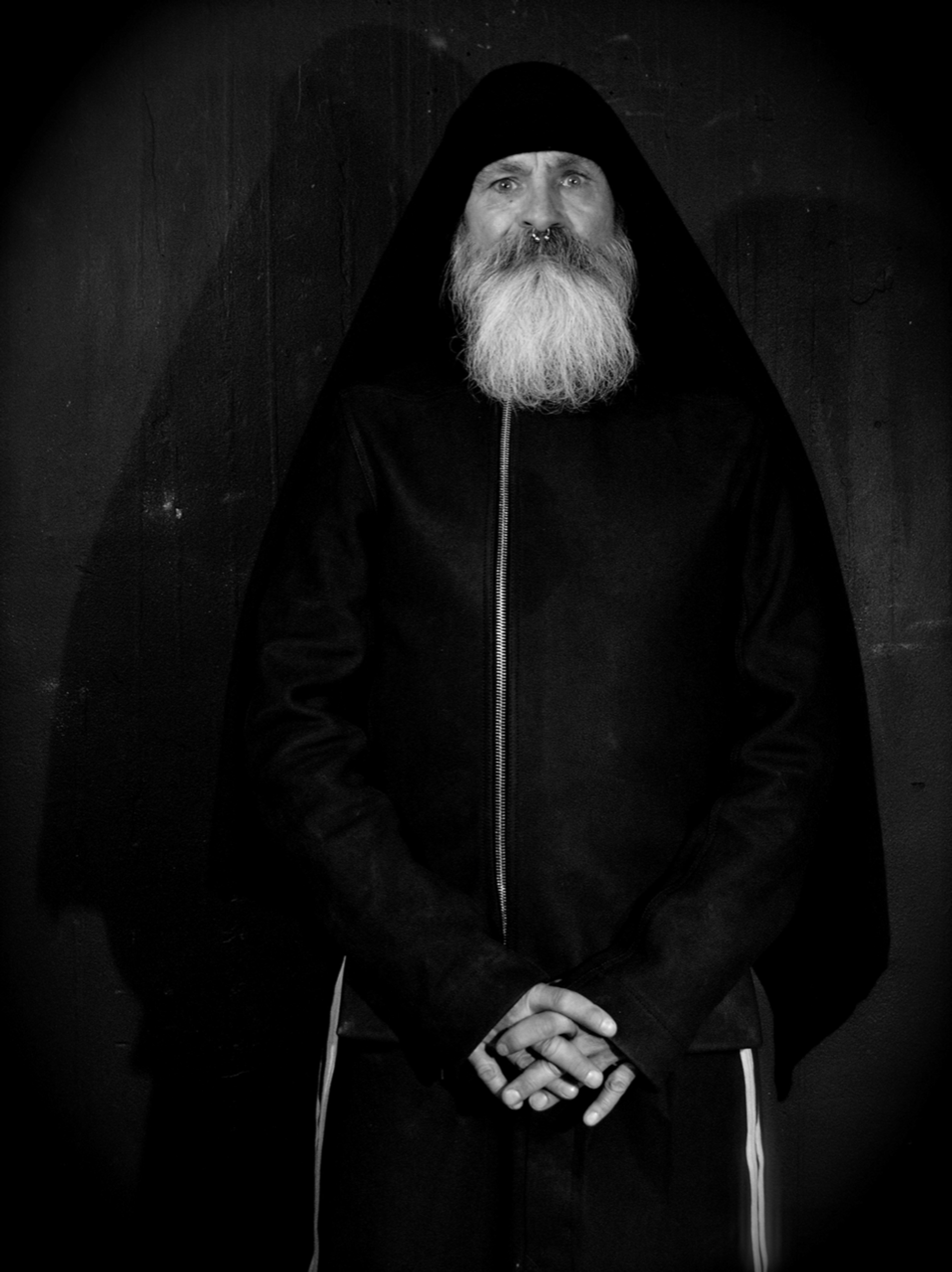

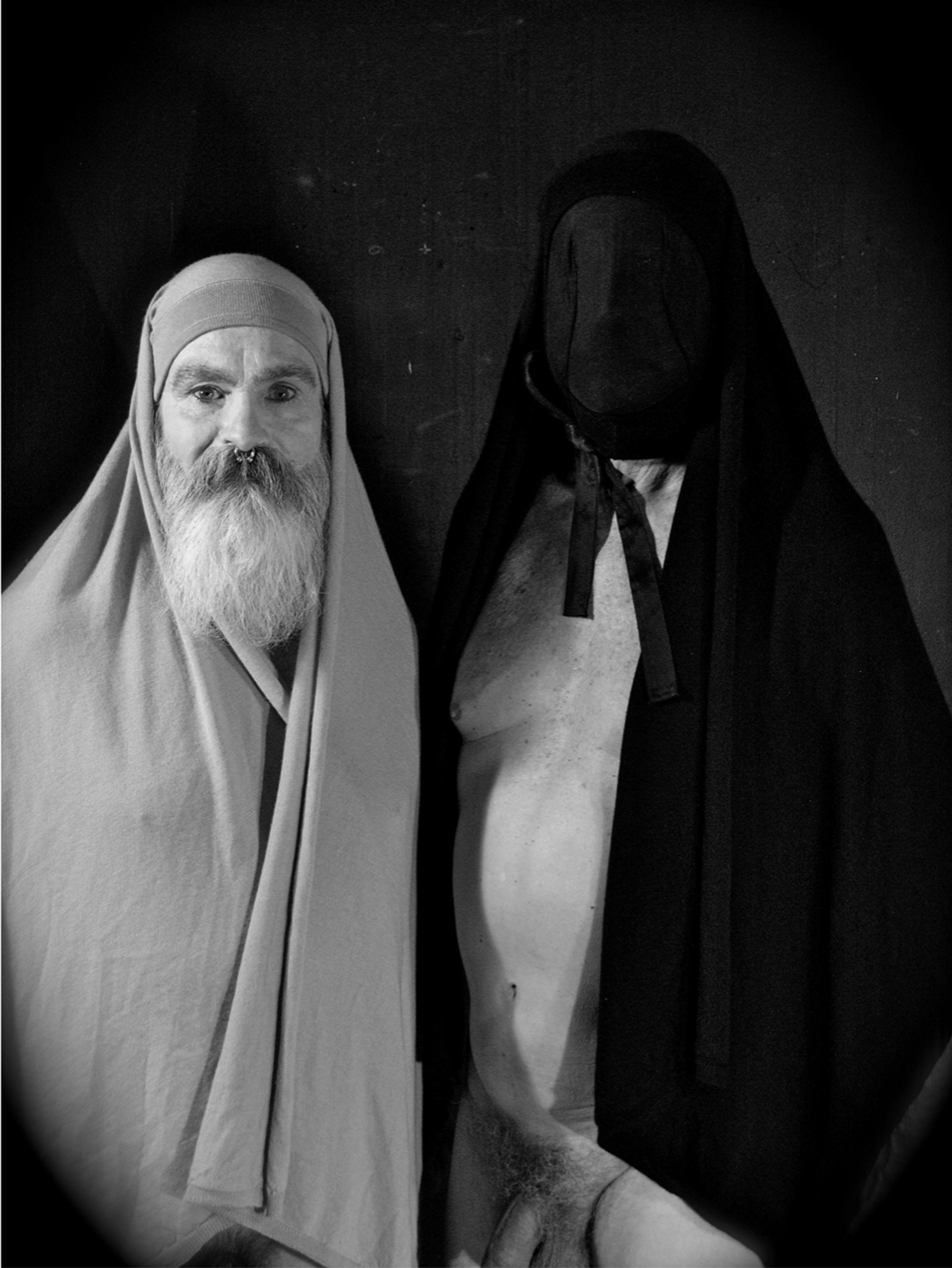

Rick actually co-directed the film Hustler White by Bruce LaBruce. You have to watch it because it’s a real slice of our lives at that moment. Many of our friends are in it. But at some point there was some kind of friction, and I got Rick fired because I couldn’t stand him anymore. We didn’t talk for ten years. He became a fetish photographer and had a gallery. Eight years ago I asked him to do a lookbook for one of my men’s collections, and he did the most beautiful one. It was all old guys, including his father — he got his totally homophobic father to be part of it. Anyway, I think afterwards we all realized that everyone ended up where they were supposed to be.

Rick Owens AW-14 lookbook photographed by Rick Castro

BW: So at this point you’re the menswear designer at Lamy, Michéle’s brand.

RO: Yes, but it was an expensive thing to do, and I slipped into doing women’s, which was the bread and butter of the business. But then Michéle hit a financial plateau — to grow bigger she would have to start producing outside of L.A. It became tedious and wasn’t fun for her anymore — in terms of price and competitiveness. She started wandering away from it, and her husband took over the business. He wasn’t so into it though and let it go after a while. Michéle focused entirely on her restaurant, and I started my own label around that time.

BW: It was your first time to do something under your own name, right? How did you get the designs into stores? I want to know the Maxfield and Charles Gallay stories.

RO: I went to Maxfield first but couldn't get an appointment with anybody. Then I went to Charles Gallay.

BW: With an appointment?

RO: No, cold call. I just walked in, with my stuff in duffel bags, walked up to the manager and said, “Hey, I have this stuff. Do you think I could sell it here?” I don’t remember if I had that many clothes, but I showed some belts, and she said, “Let me call Charles.” The belts were complex corsets, very shaped, a lot of lace up, and some ribbon. I had one in leather and one in tulle. I found the tulle in a hat making supply store in downtown L.A. It was so beautiful. Based on these belts, I got a real appointment with Charles Gallay. I took my duffel bag of clothes to his warehouse somewhere in century city. It was a concrete nondescript industrial complex, and when I walked in, there were rows of racks with designers including Alaïa and Versace. It was so sophisticated. I said, “I’m broke. Can you give me 50 percent of the order now?” And they said yes. I think that was the time where fashion buyers were adventurous pioneers. They went and sought for designers in grottos; they went to a fashion show in the middle of nowhere.

The infamous RO corset, sent over by his former fitting model Dafne

BW: How big was this first order?

RO: Oh, tiny of course. It must’ve been maybe 10000 dollars, probably less.

BW: Did you produce the clothes in-house and financed it with the 50 percent you got from the sales?

RO: Yeah, the first couple of times. Then we moved. Michéle and I got held up at gunpoint at night, and the next day we went to Chateau Marmont. That’s where we lived for the next two years, and it’s where I really got rolling.

BW: That sounds expensive.

RO: It was reduced rent, but we left the Chateau owing them a lot. We ended up having to pay for a long time, especially for my bar bill.

Then Michéle opened Les Deux Cafes, which became a very popular nightlife spot. I had moved my studio across the street on Las Palmas Avenue. The place used to be a stockroom for a magazine stand. It was wonderful though, so we moved into that together and both kind of started from zero. We ate at the restaurant and went across the street to my studio every night. You had to go up a ladder to our mattress, and we went to the gym for showers. Gradually, I was able to get the spaces next to my place and combined them. But it was in a really dangerous neighbourhood. We were on the ground floor and had to drag creaking iron gates in front of the windows at night to lock ourselves in. It was sinister, glamorous, sleazy, and gritty, and it was pretty great.

BW: I think this is something a lot of young designers can relate to: the struggle of living in such close proximity to your work. You wake up and stare at the failure or success of whatever you’re working on at the moment.

RO: It’s still very much the same for me. We live on the two top floors of this house, and the rest is office. I would always want to live with my work; it's essential to me. But at that time, the studio became a store almost, because I had racks of extra clothes, and people would come over and pick stuff up. It wasn’t something I encouraged though. Watching people try things on bored me to tears. Michéle reminded me recently that Sydney Toledano had made an appointment to look at my racks, and we ended up going to the beach that day because I forgot. Another day a woman from Vanity Fair came by, and I didn’t have any stock to show besides one corset. That’s how it went for a few years. Then I went to Europe with Charles Gallay, and he introduced me to other stores including Henri Bendel, Joyce from HongKong, Linder Dresner from Chicago.

BW: What was his benefit as a stockist to introduce you to other stores? Didn't he want to sell you exclusively?

RO: He wanted me to survive, and I couldn’t survive just on him. He wanted someone he was promoting in the right store, so that he would eventually sell more. I started selling to Henri Bendel in New York, which became my main New York store. Somehow André Leon Talley saw my stuff in store windows, found out my number, and called me out of the blue, “I am calling from Vogue and you must meet Anna.” I told him I would be there next month, as I periodically went to New York to meet buyers in a hotel room.

Rick Owen's studio on Las Palmas Avenue

BW: Speaking of selling, there is no sales agency or sales team at this point, right?

RO: No. There were only three people: me, Dafne, who never got paid, and Ricardo. He had been my samplemaker when I worked at the knockoff place. When I moved over to Michelle, he moved with me, and he also came with me when I moved to my studio. He was Mexican, didn’t speak much English, and was very gruff. And every once in a while he wouldn’t show up to work because he was in jail because he drank too much and started a fight or something. When he wasn’t working for me he was doing construction. He was so devoted and talented. He sewed everything I made, and I paid him in cash. To this day, I think his craftsmanship and capabilities shaped my design identity. He helped me establish my garment construction language. He always talked about building some kind of hut in Mexico to retire. We lost track of him, but it was always his plan to be off-the-grid.

BW: I’m sure he googled you every once in a while and waited for his mention.

RO: I have looked for him, and I have mentioned him. Because I felt like he deserved to be recognized. We’ve never been able to find him. He must be in his 80s now, so I hope he’s good.

BW: Wow, I didn’t know about this. I also want to touch on the fairytale-esque story that’s often mentioned when talking about RO’s history: Anna Wintour started supporting you because she saw one of your jackets on Kate Moss in French Vogue?

RO: It might have been that, but it really started with André Leon Talley calling me. I met Anna in Paris in a hotel room full of flowers, because all the brands send her flowers. I came with my duffel bag, dumped everything on the floor, and Dafne tried things on. Then we left.

It all happened around the same time: the French Vogue picture by Corinne Day, Bendel, Annie Leibovitz’s picture in American Vogue, my first runway show in New York, and the CFDA award. Things happened quite naturally for me in the end, even though it was a slow start. Through a mutual friend I met Carine Roitfeld. One time we hung out at the beach because she was shooting in Santa Monica with Mario Testino. Years later Carine goes, “I had no idea you were a designer. Why didn’t you say anything?” I just said, “I don't want to be a douche”. I think how my jacket ended up in French Vogue shot by Corinne Day was through the stylist Panos Yiapanis, because he started borrowing my clothes from Hollywood Boulevard. I don’t know how he found me; I think it might have been an article in Dutch Magazine. There was a little blurb about me with a picture of Goddess Bunny in my clothes. Bunny was a beautiful trans person, who had multiple sclerosis and was in a wheelchair. She was a fixture in the LA underground scene and would get out of her wheelchair and tap dance. Anyways, Panos is the one who put Kate Moss in that leather jacket in French Vogue. Later on, when Corinne died, someone told me that she was buried in that jacket.

BW: With this growing attention around your name, you were in need of actual sales people. How did you meet Elsa Lanzo, CEO of Rick Owens, and Luca Ruggeri, Owenscorp Commercial Director?

RO: Elsa and Luca came to Hollywood Boulevard to find me.

Goddess Bunny in Dutch Magazine

BW: Was that before the New York fashion week show?

RO: Yeah. They saw me in the Maria Luisa store in Paris. Elsa and Luca were sales agents and sold Alexander McQueen, Olivier Theyskens, and Ann Demeulemeester to Maria Luisa. Luca came to me and said, “If you sign a global distribution deal with us, we can introduce you to manufacturers and organize licensing.” I immediately said yes because I was desperate. Things were happening for me but I was still broke. Michéle and I, even though we had a great life, were surviving on dinner at the cafe every night. I could barely pay rent and was always behind. So I said yes to Luca, but then he didn’t call me for the longest time, and I signed with Totem Paris. They carried Raf Simons, which was good enough for me. I was happy. But when the showrooms started, it was a bunch of designers all in one room. You couldn’t tell who’s who, and I didn’t sell anything for two seasons. I sold to my regular clients but now had to pay commission on top. Months pass, Luca calls me, and goes, “We’re ready to sign.” I said, “You fucking took too long!” They had to buy me out. That’s how I started with Luca and Elsa.

The funny thing is that I went to a Raf Simons show years later, and they wouldn’t let me in at the door. As I walked away slightly confused with my invite in hand, the Raf PR caught me and brought me in. Later on I heard that it was because someone from Totem didn’t want me there. Anyways, Elsa and Luca drove me around Italy to view different manufacturers who all said no to us. Finally, we found one manufacturer in Concordia. The man didn’t really want me, but the wife thought I was interesting. So they took me on.

BW: Did you produce the collection for your first show in Italy?

RO: Yes, that first Italian-made collection was what we showed in the first show in New York. The music for that show was so good. It started with Iggy Pop, Alice Cooper’s “Sick Things,” which is such an anthem for me, and Alien Sex Fiend “Smells Like Shit.” It was hilarious that all the editors were sitting through that.

BW: I have been begging your team to make a show playlists since last year, and while your shows have moved to Paris, you still work with the same factory in Concordia, where your first runway collection was produced as well as with the same people who drove you around Italy trying to find a factory.

RO: I am still in Concordia decades later and work with the same people. We bought the factory from them.

BW: You’re like Hermès who own their own alligator farms.

RO: Actually, they have pig farms in Concordia. That’s what supported their factory for a while. We always used to joke that we were being funded by Prosciutto.